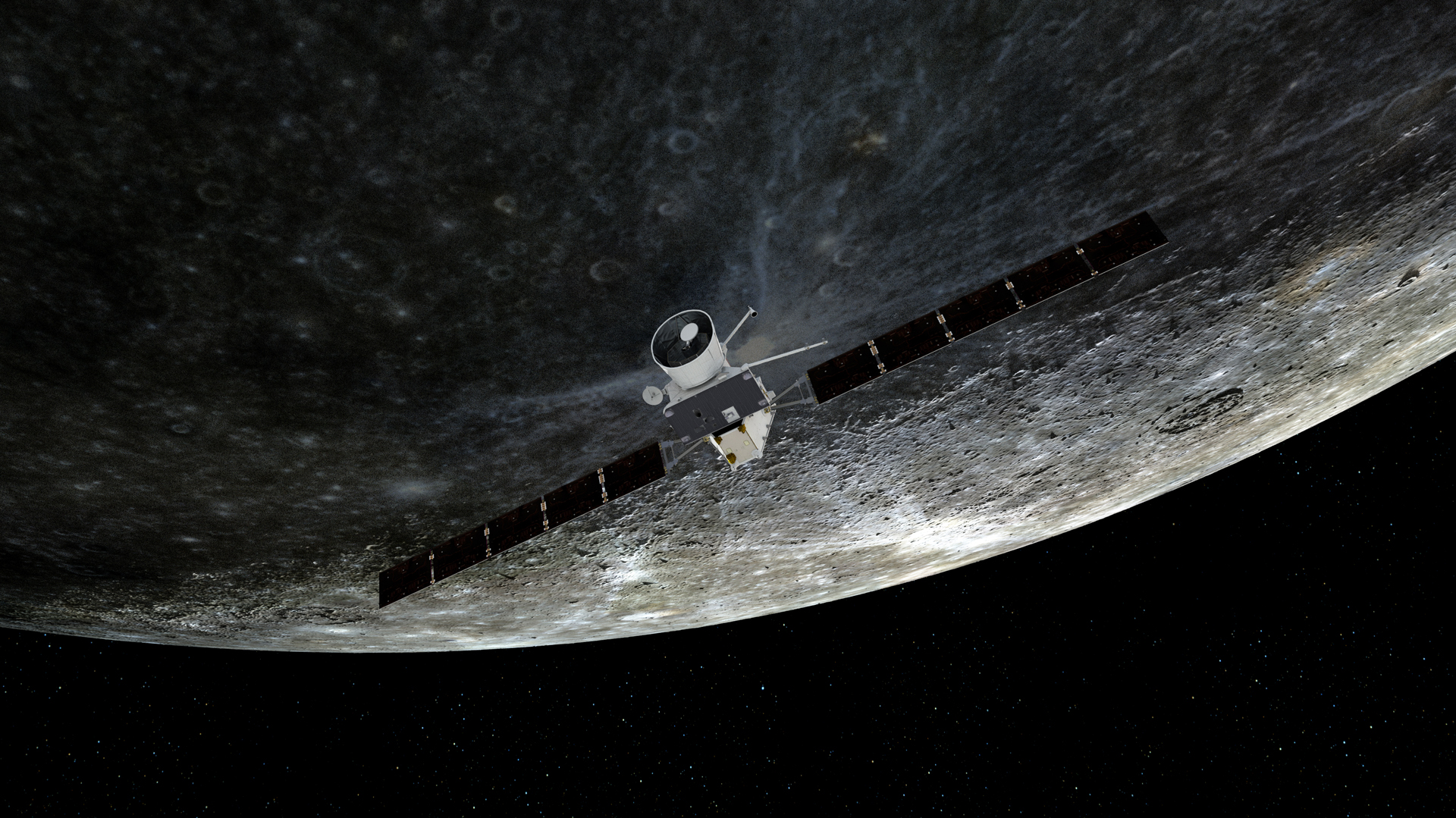

Europe's BepiColombo spacecraft zooms within 150 miles of Mercury in close flyby

The flyby will help the BepiColombo spacecraft reduce its speed so that it can enter Mercury's orbit in two and a half years.

Europe's Mercury probe BepiColombo will take a close look at its target planet on Monday (June 19), and we can expect some exciting new images to reach Earth soon after that.

The flyby will be BepiColombo's third of Mercury and will see the spacecraft whizz past the planet at a superclose distance of just 147 miles (236 kilometers) at 3:34 p.m. EDT (1934 GMT). That's closer than the probe's two orbiters will circle during the main mission.

The main goal of the flyby, however, is not to take stunning close-ups of Mercury's surface, but to slow the probe down using Mercury's gravity so that it can enter the planet's orbit in late 2025.

"Our spacecraft began with far too much energy because it launched from Earth and, like our planet, is orbiting the sun. To be captured by Mercury, we need to slow down, and we're using the gravity of Earth, Venus and Mercury to do just that," ESA flight dynamics expert Frank Budnik said in a statement.

Related: 10 strange Mercury facts

The BepiColombo mission, a joint project by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), is only the third spacecraft in history to take a look at Mercury, the solar system's innermost planet, which is notoriously difficult to study.

Although Mercury is on average 10 times closer to Earth than Jupiter is, it takes just as long to get to the innermost planet as it does to reach the gas giant. That's because a Mercury-bound spacecraft has to constantly brake against the powerful gravitational pull of the sun. To do that BepiColombo, which launched in 2018, is making carefully calculated flybys of planets along its way while in orbit of the sun. The probe has previously flown past Mercury twice, in October 2021 and in July 2022. Prior to that, the spacecraft also visited Earth once and Venus twice.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As BepiColombo starts feeling Mercury's gravitational pull, it will be traveling at 3.6 km/s [2.2 miles per second] with respect to the planet. That's just over half the speed it approached during the previous two Mercury flybys," Budnik said.

The flyby will further reduce the spacecraft's velocity magnitude compared to the sun by 0.5 miles per second (0.8 km/s), and change its direction by 2.6 degrees, Budnik added.

There will be three further Mercury flybys before BepiColombo is finally slow enough to be captured by the rocky planet, which is only somewhat larger than Earth's moon: in September 2024, in December that same year and the final one in January 2025.

Since some of the spacecraft's instruments are operational during the journey, scientists are excited to use the opportunity to make measurements of the boiling environment around Mercury. BepiColombo also carries three low-resolution monitoring cameras that will be busy snapping black-and-white images of the little-explored rocky word during the flyby.

The previous two Mercury flybys have already produced interesting science results, Johannes Benkhoff, BepiColombo project scientist at ESA, said in the statement. The probe made the first-ever measurements of the planet's feeble southern inner magnetosphere, for example, and revealed the composition of charged particles in this region.

"Collecting data during flybys is extremely valuable for the science teams to check their instruments are functioning correctly ahead of the main mission," Benkhoff said. "It also provides a novel opportunity to compare with data collected by NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft during its 2011–2015 mission at Mercury from complementary locations around the planet not usually accessible from orbit."

The BepiColombo spacecraft consists of two orbiters that are currently cruising through the solar system stacked on top of each other. As a result of that, some of the probes' instruments are covered during the cruise. But during the Monday flyby, two instruments designed to measure the shape of Mercury's surface and study its gravitational field will collect data for the first time. The orbiters' main, high-resolution cameras, unfortunately, won't be available just yet.

Two probes have previously studied Mercury up close. NASA's Mariner 10 flew past Mercury three times in 1974 and 1975, obtaining the first-ever images of the scorched planet. And NASA's MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging' (MESSENGER) mission orbited the planet from 2011 to 2015.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

-

mbee1 The USA went there a long time ago with a 4 year long orbital spacecraft mission to do it. The European mission is basically a stunt to make sure the bureaucrats are doing something to justify their salary and retirement checks. Total waste of funds from a science standpoint.Reply -

jean-luc suchail Reply

We do not have the same instruments on board. Much more science will come, the goal is NOT to be the first, but to be the BEST.mbee1 said:The USA went there a long time ago with a 4 year long orbital spacecraft mission to do it. The European mission is basically a stunt to make sure the bureaucrats are doing something to justify their salary and retirement checks. Total waste of funds from a science standpoint.