Military interest in the moon is ramping up

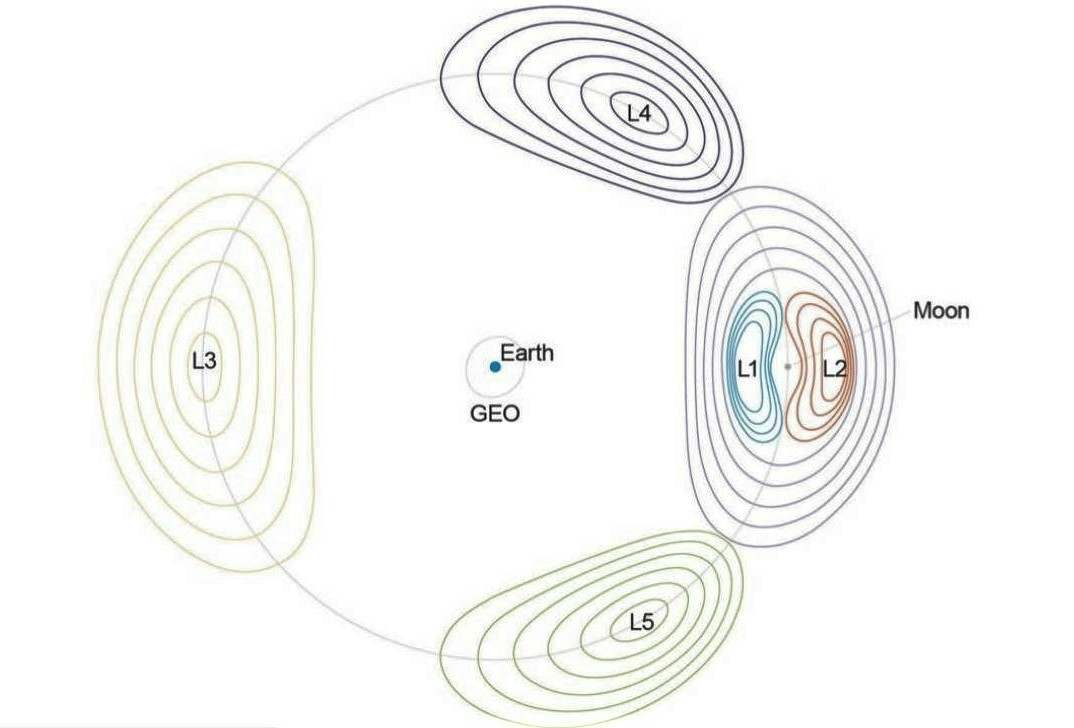

"Cislunar space has recently become prominent in the space community and warrants attention," a recent Air Force Research Laboratory document states.

There is growing interest in protecting strategic assets in cislunar space, the realm between Earth and the moon.

The U.S. Space Force is not the only entity engaged in reflecting on the topic of how best to extend military presence far from Earth. Other nations such as China are doing so as well.

Parallel to air, land and sea skirmishes between nations here on Earth, is cislunar space, and perhaps the moon itself, an emerging military "high ground" and new territory for conflict? There’s a variance of views, according to experts Space.com talked to.

Related: Is Earth-moon space the military's new high ground?

Cislunar primer

Earlier this year, the Air Force Research Laboratory distributed "A Primer on Cislunar Space," a document targeted at military space professionals who will answer the call to develop plans, capabilities, expertise and operational concepts for the region.

"Cislunar space has recently become prominent in the space community and warrants attention," the document explains.

As the U.S. Space Force "organizes, trains, and equips to provide the resources necessary to protect and defend vital U.S. interests in and beyond Earth orbit," the primer also underscores that new collaborations will be key to "operating safely and securely on these distant frontiers."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: US Space Force has new guidelines for working at and around the moon

Visionary wish list

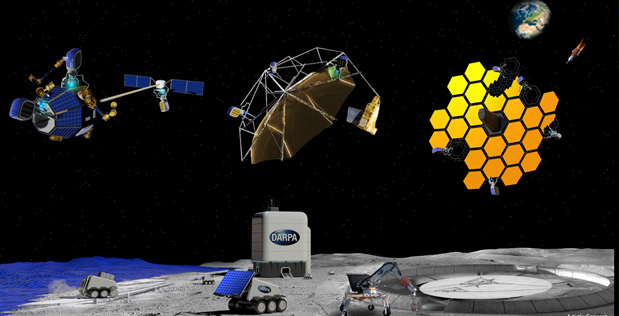

In the interim, the Defense Sciences Office at the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has blueprinted a wish list of new research to enable the fabrication of future space structures — including the use of lunar resources to enable those structures.

Some of that research will be performed by the Novel Orbital and Moon Manufacturing, Materials and Mass-efficient Design program, or NOM4D.

NOM4D aims to develop new materials, manufacturing, and design technologies to enable future structures to be built in Earth orbit or on the moon's surface. For instance, large solar arrays, large radio frequency reflector antennas and segmented infrared reflective optics are visualized.

Building a precision structure while minimizing the required mass fraction brought from Earth will enable a spectrum of Department of Defense systems to be built using lunar-derived materials, DARPA officials say.

"For the purposes of understanding the hypothetical use case, proposers may consider fabrication of structures on orbit or on the lunar surface for relaunch back into orbit as long as the proposed system is consistent with the Outer Space Treaty," NOM4D documentation explains.

Contract negotiations are currently underway, with the selection of NOM4D winners soon to be announced, DARPA has advised Space.com.

Military moon

The U.S. military has eyed the moon before.

As far back as 1959, when NASA was still picking its first astronauts, the U.S. Army was concocting plans for a moon base, under the title of Project Horizon, explained Robert Godwin, a space historian and owner of Apogee Books, a Canadian publishing house that examines a variety of space history topics.

Some details of the U.S. military's past interest in the moon remain classified to this day, Godwin said. In particular, there were looks at a nuclear bomb detonation in orbit around the moon that would empower "the weapon" — an X-ray laser that would take out enemy satellites and spacecraft, he told Space.com.

That was then. But valuable U.S. assets on the moon, such as planned commercial ventures there, will make "the military presence to ensure their safety," Godwin said, "almost inevitable."

"Back in 1959, the U.S. military was fretting over whether they could get supplies of toilet paper up there," he added. Looking back, he said those working on Project Horizon were coming out of World War II, practiced in moving hundreds of thousands of tons of heavy equipment around the world.

"The fact they were going to have to make that equipment 'go up' instead of 'sideways' seemed to be secondary to their thinking," Godwin said. To that end, things have progressed. For example, scientists now believe that there's a lot of water on the moon.

"But at the end of the day, you still go skin the cat. The way to do that could be more affordable now," Godwin said.

Related: The search for water on the moon (photos)

Record of choices

Daniel Deudney teaches political science, international relations and political theory at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. He is author of "Dark Skies: Space Expansionism, Planetary Geopolitics and the Ends of Humanity" (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Particularly since the middle years of the 20th century, Deudney said, humanity has been forced to make governance decisions about new technologies, whether by default or design, with momentous implications.

"The overall record of choices made has been mixed. Perhaps the most notable failure was the weaponization of nuclear energy," Deudney said. "Momentous decisions have also had to be made about the vast and alien realms beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. Here the pace of technological advance, and thus the need to choose, has been slower. But here too the record has been quite mixed."

A major mistake was the weaponization of the rocket, which has almost certainly increased the probability of nuclear war, Deudney said.

Momentum is building

In part because of the sway of "frontier" analogs in thinking about space, a key fact about choices for Earth space has not been widely grasped, Deudney told Space.com. "Earth space, unlike frontiers, is marked not by 'both/and' opportunities, but by 'either/or' ones. Pursuing the military options will preclude, or make much more difficult, the realization of other paths," he said.

Due to the falling costs of accessing orbital space — long a bottleneck for all space activities (particularly those involving significant infrastructures) — it is increasingly likely that major space initiatives will be pursued, Deudney said.

"Due to the deterioration of terrestrial Great Power relations, the waning of the arms control and disarmament movements, and the decay of the Outer Space Treaty regime," Deudney said, "momentum is gathering for further major militarization and weaponization of space technologies and locales, most notably on Luna [the moon]."

Fog of peace

We need more governance in outer space, for all actors, said Jessica West, a senior researcher with Project Ploughshares, a Canadian peace research institute. She also serves as managing editor for the Space Security Index project.

"We need clear rules, and we need restrictions, and we need processes in place to implement them," West said. "Finally, we can no longer accept the fog of peace that shrouds military activities in outer space, whereby they are deemed 'peaceful' on the one hand yet outside the scope of rules and regulations for peaceful use on the other."

Space is harsh, West added, and the lunar environment particularly so. "We need to be promoting cooperation and commonality and working through frameworks of trust and transparency."

Deterrence and diplomacy

Michael Krepon is co-founder and distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C. The group delves into independent analysis and policy innovation in its international security research. He is author of "Winning and Losing the Nuclear Peace: The Rise, Demise, and Revival of Arms Control" (Stanford University Press, 2021).

"Major powers seek advantage and to avoid disadvantage," Krepon told Space.com.

If the purpose behind military activities that stretch out to cislunar space and to the moon itself is to seek dominance, the outcome will be foreordained, Krepon said. "Major powers that cannot accept someone else’s dominance and have the means to negate it will act to do so."

Those negation strategies are termed "deterrence" when it comes to nuclear weapons. "Deterrence is meant to be dangerous; otherwise it wouldn’t deter," Krepon said. This is why deterrence capabilities look a lot like war-fighting capabilities. Because deterrence was and is so dangerous, major powers also had to signal during the Cold War that they preferred not to use war-fighting instruments, he said.

"Diplomacy was and is needed for purposes of reassurance — to take the sharpest edges off deterrence. We’ve managed to avoid nuclear war — so far — by the combination of deterrence and diplomacy. We forget this lesson at our peril," he said.

Related: Is war in space inevitable?

Wide waterfront

Indeed, diplomacy can cover a wide waterfront, Krepon added. "One diplomatic mechanism is the prevention of dangerous military practices and the codification of responsible and irresponsible behavior."

Krepon said that he's hearing echoes of the very origins of nuclear deterrence: People barely old enough to remember just how dangerous the nuclear arms race truly was are saying that warfare in space is inevitable and there’s a need to dominate this new war-fighting domain.

"This is dangerous thinking. It’s predicated in assumptions that badly need to be unwrapped," Krepon said. For example:

- Is escalation control likely in the event of space warfare?

- Is space debris management likely?

- Is a peer or near-peer competitor likely to accept being dominated in space warfare?

- Does that competitor have the means to prevent being dominated?

- What are the likely consequences of seeking "war-winning" capabilities?

- What are the likely consequences of assuming that space warfare is inevitable?

"If the answers to these questions are troubling, then we need to get to work on the diplomacy piece," Krepon said.

Destabilizing or threatening?

So there's a fair amount of cislunar angst out there. But Todd Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., has a different viewpoint.

"I really don’t think there’s much to this," Harrison advised. Though the U.S. Space Force knows that eventually it will need to be concerned about what’s going on in cislunar space, he said, "we’re not at that point yet."

There could be some ancillary military benefits in building a very large aperture antenna in space, Harrison said. "Maybe that gives you some new sensing capabilities. But I don’t see it as being destabilizing or threatening to other countries."

Threat-hyping

Harrison said there are some cislunar "threat hypers" out there — and he is not among them.

"Cislunar space is a very low priority for the Space Force compared to all the things going on in Earth orbit that it needs to be concerned about," Harrison told Space.com.

In Harrison’s thinking, the most promising lunar resources are for civil and commercial space ventures.

"By far, that’s what we’re looking at," Harrison said, pointing to using materials from the moon for propulsion or building structures. "NASA is the lead when it comes to cislunar space. And that’s the way it should be."

Still, in casting a futuristic eye outward, Harrison advised that "where commerce goes, conflict eventually follows."

There could be a military role, Harrison said, albeit 20, 30 or maybe even 50 years into the future, of helping to protect trade routes and U.S. interests. "But we’re a long, long way from that happening."

Leonard David is author of the book "Moon Rush: The New Space Race," published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.