Astronomers Find Fossils of Early Universe Stuffed in Milky Way's Bulge

Astronomers peered into the dusky bulge of the Milky Way and found some of the oldest known stars in the universe.

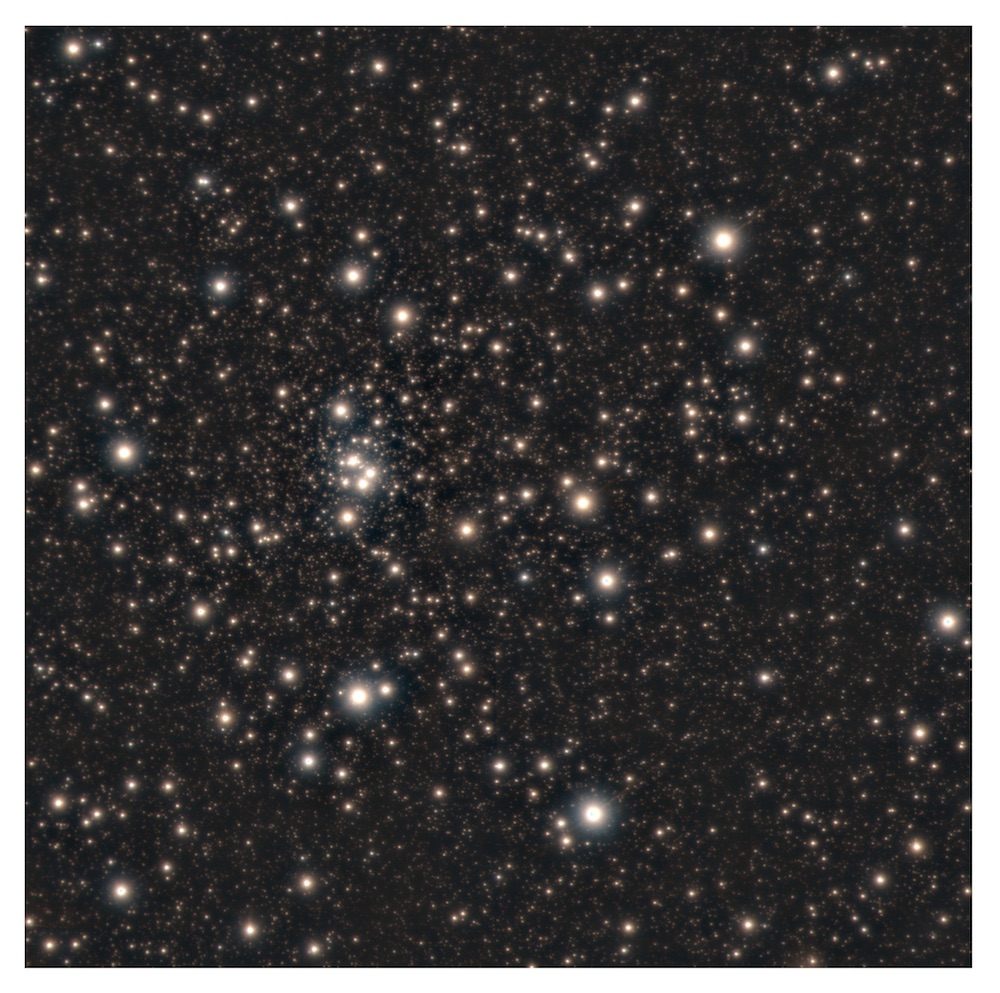

In a study to be published in the April 2019 issue of the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers analyzed a cluster of old, dim stars called HP1, located about 21,500 light-years away from Earth in the gut of our galaxy's central bulge. Using observations from Chile's Gemini South telescope and archival Hubble Space Telescope data, the researchers calculated the age of the stars to be roughly 12.8 billion years old — making them some of the oldest stars ever detected in either the Milky Way or the universe at large.

"These are also some of the oldest stars we've seen anywhere," study co-author Stefano Souza, a doctoral candidate at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, said in a statement. [15 Unforgettable Images of Stars]

The Milky Way's bulge — a bulbous, 10,000 light-year-wide region of stars and dust popping out of the galaxy's spiral disc — is thought to contain some of the oldest stars in the galaxy.

Previous studies have tried to prove that ancient stars were hiding in the Milky Way's bulge by studying HP1 and other nearby clusters. But Souza and his colleagues analyzed the problem with unprecedented resolution, thanks to an imaging technique called adaptive optics — essentially, a method that corrects pictures of space for light distortions caused by Earth's atmosphere.

By combining these ultra-high-definition observations and reviewing archival footage from Hubble, the team calculated the distance to Earth for even the dimmest, most dust-covered stars in HP1. These distances helped the team to calculate each star's brightness. The intensity and color of each star's light, in turn, reveals the star type — whether it was a dwarf or a giant, for example, or whether it emitted a lot of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium.

The weight of a star's elements — also called its "metallicity" — is crucial information for scientists who study aging celestial bodies. Researchers suspect that the universe's earliest stars formed out of primordial clouds of pure hydrogen gas. The universe's first helium atoms are thought to have emerged from the nuclear reactions at the hearts of these ancient stars.. Eventually, as more and more stars were born, every other element currently known to humans exploded into existence.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stars that produce a lot of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium are therefore considered to be relatively young in the cosmic scheme of things. So, when the Gemini researchers saw that the stars of HP1 were extremely light on heavy elements, they knew they had an old cluster in their sights.

The team calculated that the stars likely date to the first billion years of the universe's life — making them roughly 12.8 billion years old.

"HP 1 is one of the surviving members of the fundamental building blocks that assembled our galaxy's inner bulge," lead study author Leandro Kerber of the University of São Paulo and Brazil's State University of Santa Cruz,said in the statement.

The fact that the Milky Way hides ancient stars in its bulging midsection means the area is the perfect location for studying our galaxy's awkward childhood years.

- 5 Reasons We May Live in a Multiverse

- 9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why We Haven't Found Aliens Yet

- Gallery: Our Amazing Sun

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.