One of the oldest known annual meteor showers, peaking early this week, may unfortunately be hindered by an almost-full moon.

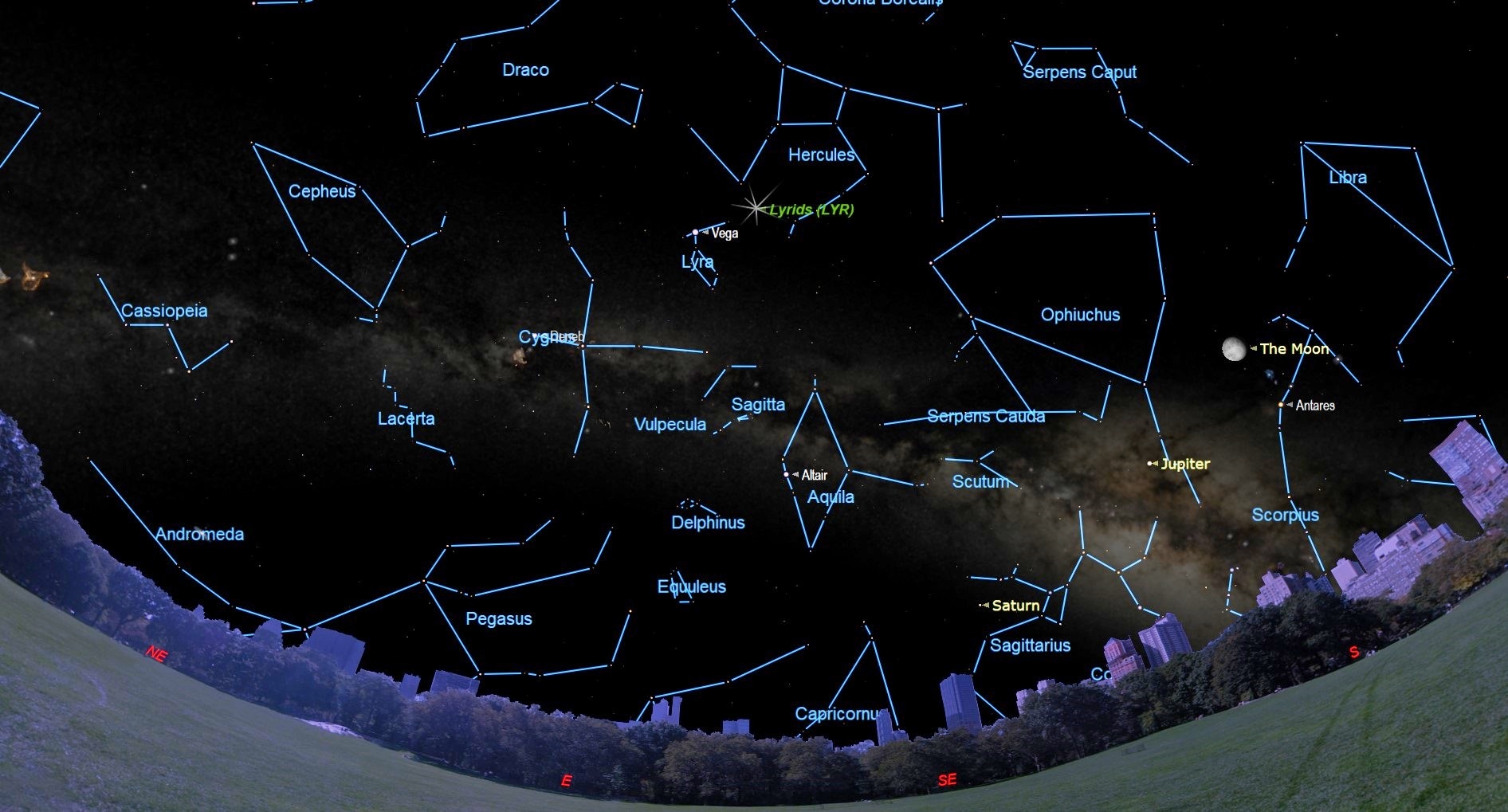

The moon reaches full phase during the overnight hours of April 18-19, so many will likely dismiss this year's performance of the Lyrid meteor shower as unobservable. The peak of activity is expected during the night of April 22-23; when the moon rises at about 11:30 p.m., the shower radiant will be less than halfway up in the northeastern sky. (The American Meteor Society lists the peak as April 21-22, but both nights should have similar rates.) That radiant is located to the lower right of the brilliant blue-white star Vega in the little constellation of Lyra, hence the name "Lyrids." (A meteor shower's radiant is the spot from which the shower's meteors appear to be streaking; they can appear all across the sky, but their tails will point to that spot.)

The orbit of the Lyrid meteors strongly resembles that of Thatcher's Comet, which swung past us during the spring of 1861 and has an orbital period of approximately 415 years. In 1867, astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle confirmed the link between this comet and the Lyrids; the meteors that we see from this display are the tiny particles that were shed by the comet on its previous visits through the inner solar system.

Related: The Most Amazing Lyrid Meteor Shower Photos of All Time

Lyrid surprises

The April Lyrids have sometimes provided spectacular displays, as in 687 B.C., when Chinese records said "stars fell like rain," and it's happened at least a dozen other times since then. The story is often told of how residents of Richmond, Virginia, were rousted out of bed by the fire bell on the morning of April 20, 1803. The fire that had broken out in the armory was quickly extinguished, but this gave the townspeople a chance to see meteors falling in great numbers from all parts of the sky.

The event is also described in a letter published in the Raleigh, North Carolina, Register:

"We, the undersigned . . . being on Wednesday night, the 20th of April, out at a fishing party, and returning home about 1 o'clock a.m., were alarmed with the appearance of a shooting of stars; the whole hemisphere as far as the extension of the horizon seemed to be illuminated; the meteors kept no particular direction but appeared to move every way. We viewed the phenomenon for the space perhaps of half an hour with amazement, during which time no intermission appeared. We distinctly heard a hissing in the air but heard no reports. The above statements may be relied on as facts" (signed by four men).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Similar accounts came from New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Delaware.

The meteor outburst of 1803 was completely unexpected. Very little was known about meteors in the 18th and early 19th centuries, except for the slight increase in their numbers each year during early August. The Lyrids give no clues as to when another such outburst might happen; hence, the shower is always one to watch.

Moon muscles in

Unfortunately, as we alluded to at the outset, this year, the moon is going to be a problem for prospective meteor watchers. The best chance to see some Lyrids this year will be on the morning of April 23, just before morning twilight begins. Any meteor whose path, extended backward, passes within a few degrees of Vega is likely to be a Lyrid. Around 4 a.m. local daylight time is also about the time that the Lyrid radiant will be almost directly overhead from the southern United States, and not far off it for anyone in the midnorthern hemisphere. (But remember — the meteors can appear anywhere across the sky.)

In recent years, even when the sky has been dark, the Lyrids have generally been weak. They produce a brief maximum that lasts for about a day, and even then, only 10 to 20 Lyrids per hour may appear. Yet, the April Lyrids have been described as "occasionally spectacularly bright and swift." About 20-25% of Lyrid meteors also tend to leave shining trails in their wakes that persist for a few moments.

Unforeseen spectacles

And there is always the small chance of a surprise.

A brief outburst of 100 per hour occurred in 1922. Then, in 1982, rates unexpectedly reached 90 for a single hour and 180 to 300 per hour for a few minutes — easy for skywatchers to miss due to timing. "It is indeed possible that many past Lyrid outbursts were missed simply due to observational gaps," Paul Roggermans wrote in "Handbook for Visual Meteor Observations" (Sky Publishing Corp., 1989).

So, maybe it wouldn't hurt to set the alarm clock for 2 or 3 a.m. (in your local time zone) on the morning of April 23, so you can arise for a brief look out the window, moonlight notwithstanding.

Hey ... you never know.

- Lyrid Meteor Shower: Tips to See April's 'Shooting Stars'

- How to See the Best Meteor Showers of 2019

- How Meteor Showers Work (Infographic)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.