Tiny NASA moon probe can't reach lunar orbit as planned

Lunar Flashlight is now targeting high-Earth orbit, with monthly moon flybys.

NASA has a new plan for its troubled tiny lunar probe, which is struggling to reach the moon.

The spacecraft, called Lunar Flashlight, launched in December 2022 atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, on a mission to search for water ice on the moon. The cubesat aimed to test a new "green" propellant during its four-month journey to lunar orbit, but, after battling thruster glitches, it will not make lunar orbit after all, NASA officials said in an update on Wednesday (Feb. 8).

The Lunar Flashlight team will instead redirect the cubesat to do monthly lunar flybys, if possible, starting with one in June. If that works out, Lunar Flashlight will still deliver valuable science, as it will swing by the south pole of the moon, where NASA's Artemis program aims to land astronauts as soon as 2025, agency officials emphasized.

"Technology demonstrations are high-risk, high-reward endeavors intended to push the frontiers of space technology," NASA officials wrote in the update. "The lessons learned from these challenges will help to inform future missions that further advance this technology."

Related: These two tiny spacecraft will help pave the way for astronauts to return to the moon

Lunar Flashlight's Dec. 11 launch was flawless. The tiny probe soared to space alongside a private Japanese moon lander carrying the Rashid lunar rover, which was built by the United Arab Emirates. (That lunar landing mission, led by Tokyo company ispace, remains on track for a touchdown in April.)

The NASA cubesat, however, ran into trouble. Engineers noticed propulsion problems three days after launch, discovering that Lunar Flashlight was not delivering as much thrust as expected. They determined that three of the cubesat's four thrusters weren't functioning properly.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One of Lunar Flashlight's goals was to reach a near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) ahead of that path's planned use by NASA's Gateway space station, a key piece of Artemis infrastructure. The orbit's closest lunar approach brings it over the lunar south pole, where NASA wants to deliver astronauts, before zinging out far into space. (Fortunately, another tiny testbed moon mission called CAPSTONE is currently operating just fine in a lunar NRHO.)

Shortly after the thruster problems first cropped up, NASA and mission partners at the Georgia Institute of Technology estimated that Lunar Flashlight might still be able to reach its NRHO destination using a series of single-thruster firings. In January, the team spun the spacecraft at one revolution per minute and fired the thruster for several 10-minute periods. At first, engineers thought they could reach the correct orbit in 20 days. But the lone thruster began underperforming, NASA officials wrote, and "it became clear that the thrust being delivered was not enough to make it to the planned orbit."

Despite the problematic thrusters, Lunar Flashlight's other systems remain healthy, and there remains another option to bring it close to the moon. Now, NASA and Georgia Tech plan to squeeze "any remaining thrust the propulsion system can deliver" to bring the spacecraft into a high Earth orbit instead — a path that will allow flybys of the moon's lunar pole about once per month.

Maneuvers will begin Thursday (Feb. 9), with the hope of getting the probe on track to conduct its first flyby of the moon in June. Should the cubesat get there, all systems are go for the water ice hunt.

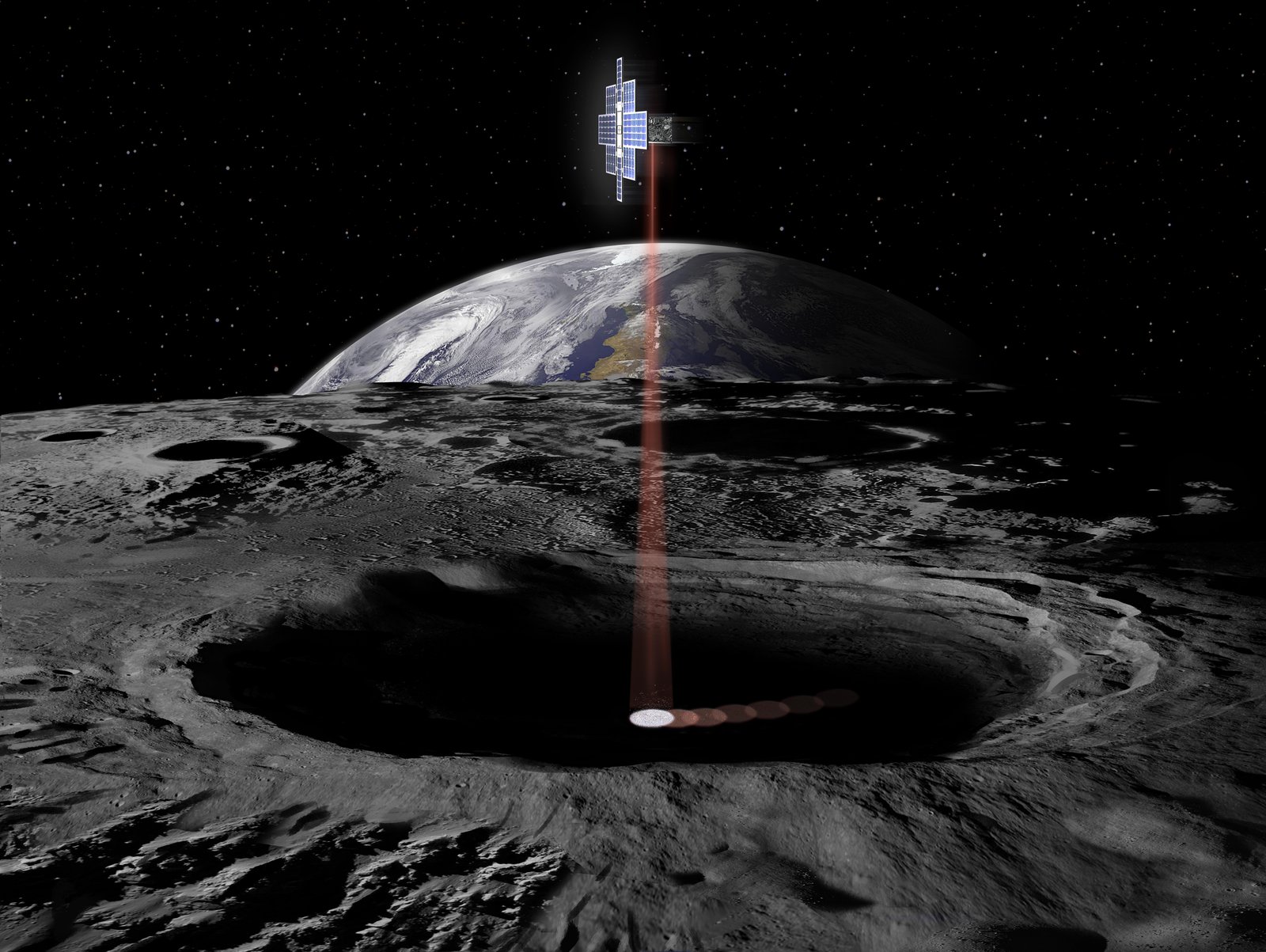

NASA officials added that the key instrument to search for water, called a four-laser reflectometer, is working well in testing. "This mini-instrument is the first of its kind and is designed and calibrated to seek out surface ice inside the permanently shadowed craters at the moon's south pole," they wrote.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

-

Unclear Engineer Isn't this the first use of the ASCENT monopropelant technology? (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Propellant_Infusion_Mission )Reply

With only 1 of 4 engines actually functioning, and that one not able to meet design specs, this seems like a serious setback for the technology.

Can we expect Space.com to keep us informed on the diagnosis of the problem and prognosis for improving reliability of this technology?