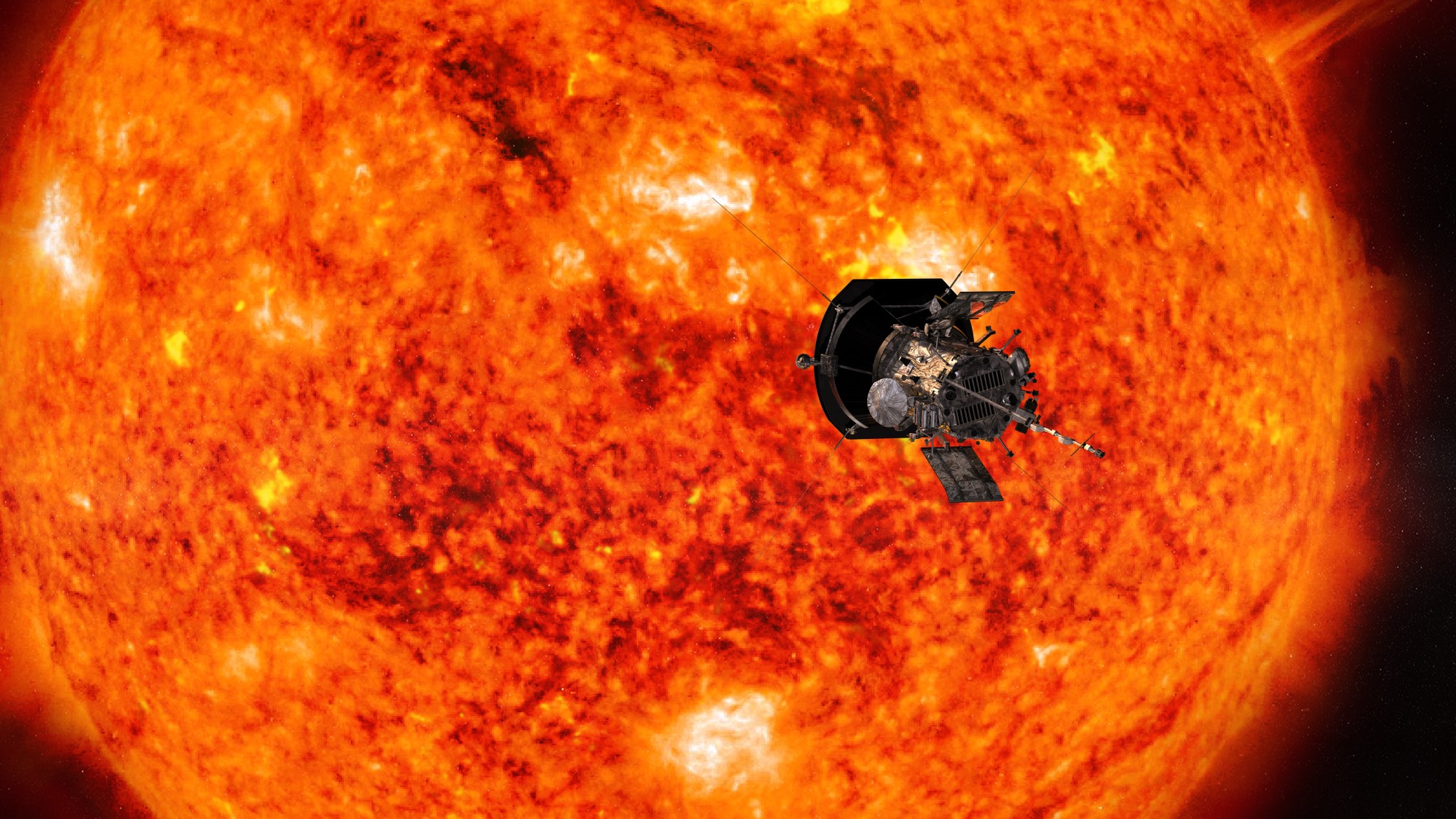

NASA's Parker Solar Probe makes its 15th close flyby of the sun this St. Patrick's Day

Raise a cold one for the spacecraft as it makes its 15th perihelion today braving blisteringly hot temperatures.

NASA's sun-touching Parker Solar Probe spacecraft will celebrate St. Patrick's Day (March 17) by making another close approach to our star. While people all over Earth enjoy a cold beer, the spacecraft will brave blisteringly hot temperatures as high as 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius) as it makes its 15th close approach to the sun, or perihelion.

According to NASA's Parker Solar Probe website, the exact time of the close approach will be 4:30 p.m. EDT (2030 GMT) when the spacecraft comes to within around 5.3 million miles (8.5 million km) of the sun's surface, the photosphere.

That is closer than the innermost planet to the sun, Mercury, which orbits the planet at over 6 times further away, around 34 million miles (54 million kilometers) from the sun. This close approach means Parker will come close to the sun's outer atmosphere known as the corona.

Related: Parker Solar Probe: First spacecraft to 'touch' the sun

One of the main missions of the Parker Solar Probe, which launched on August 12, 2018, is to investigate why the corona is hundreds of times hotter than the photosphere below it.

The corona reaches temperatures in excess of 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (1 million degrees Celsius) in comparison to the average temperature of the photosphere of around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,800 degrees Celsius). Because most of the heat from the sun comes from the nuclear fusion processes at its heart, stellar models say that the interior regions should be hotter. Additionally, the plasma of the photosphere is as much as 10 million times denser than the plasma of the corona, meaning the pressures inside the star should also be greater, so it is something of a puzzle why the corona is so blisteringly hot.

The corona is difficult to study from Earth as the light it produces is "washed out" by light from the aptly named photosphere which is only really visible when the moon covers the surface of the sun during an eclipse. At these times, the corona appears as a blazing ring of white light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To solve this lingering solar puzzle, the Parker Solar Probe must touch the corona and race through this wispy and nebulous plasma at speeds as high as 365,000 miles per hour (587,000 kilometers per hour). That makes the spacecraft the fastest object built by mankind, able to fly some 250 times faster than the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet.

Braving the heat of the corona doesn't rely on the luck of the Irish though, with the Parker Solar Probe instead depending on pioneering engineering to beat the heat. Specifically, the spacecraft is equipped with a 4.5-inch-thick (11.4 centimeter) carbon-composite shield that keeps its scientific payload at room temperature even at perihelion.

The last time the spacecraft reached perihelion was during its 14th close pass on Dec. 11, 2022, when it came to within around the same distance of the sun's surface as it will on St. Patrick's Day 2023. This isn't the closest that the Parker Solar Probe has come to the sun, however. On November 21, 2021, the spacecraft passed the sun by just a fraction closer.

Later this year, Parker will swing past Venus and adjust its trajectory with the aim of getting it even closer to the sun. The probe's planned mission includes 24 close approaches to the sun before it ends in 2025, and it will eventually come as close as 3.8 million miles (6.1 million km) from the photosphere. This is closer than any other spacecraft has come to our star and is just a tenth of the distance between our star and its innermost planet Mercury.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.