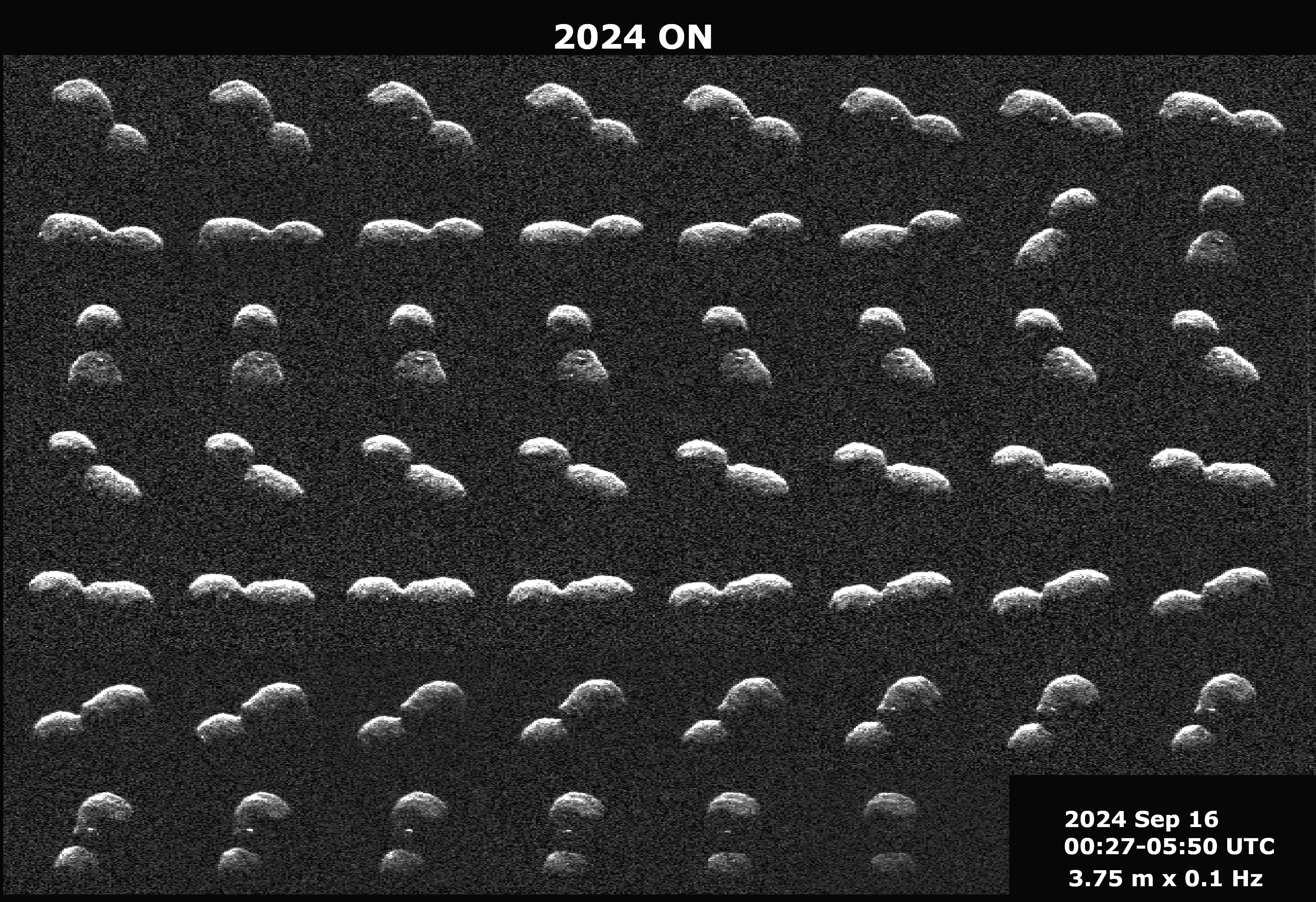

Radar images capture snowman-shaped object tumbling past Earth

It never posed a threat, but it did offer us some cool cosmic footage.

The universe appears to have sent us an early Christmas present: the large asteroid that tumbled safely past Earth last week was, in fact, two asteroids melded into one object that resembles a snowman.

The asteroid, named 2024 ON, zipped past Earth on Sept. 17 at 19,842 mph (31,933 kph), which is roughly 26 times the speed of sound. The space rock is huge — 1150 feet (350 meters) long, about the size of a skyscraper — but it safely floated past Earth at a distance of 620,000 miles (1 million kilometers), aka over 2.5 times the average distance between the moon and Earth.

"This asteroid is classified as potentially hazardous, but it does not pose a hazard to Earth for the foreseeable future," according to a recent news release from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Recent measurements of the space rock using the Goldstone Solar System Radar in California "have allowed scientists to greatly reduce the uncertainties in the asteroid's distance from Earth and in its future motion for many decades."

Those recent images revealed the asteroid's peanut shape, formed by two smaller asteroids that, eons ago, floated so close to each other that they became gravitationally bound. Ultimately, the two blended into one. The conglomerate asteroid's "lobes" are separated by a distinct neck, with one lobe roughly 50% bigger than the other.

"Bright radar spots on the asteroid's surface likely indicate large boulders," the statement says.

Related: Earth will get another moon this month — but not for long!

Scientists call such two-lobed asteroids "contact binaries," and estimate at least 14% of near-Earth asteroids bigger than 660 feet (200 meters) are of this type.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The most well-known contact binary is probably Selam, the little moonlet accompanying the near-Earth asteroid Dinkinesh, which sits between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Discovered earlier this year by NASA's asteroid-hopping Lucy spacecraft, Selam is the first contact-binary satellite found orbiting an asteroid.

By contrast, however, 2024 ON appears to be a drifter. And despite being deemed as "potentially hazardous," — NASA's term for any asteroid that floats within 4.6 million miles (7.5 million km) of Earth's orbit around the sun — the asteroid posed no danger to our planet.

Since the beginning of the year, astronomers have cataloged more than 60 asteroids whose orbits have snuck them between Earth and the moon, The Watchers reported. Tens of thousands more space rocks that hover in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter are also slowly being discovered in archival images with the help of AI-powered algorithms and the voluntary efforts of citizen scientists.

This fall, one asteroid will temporarily become Earth's second moon after our planet pulls the space rock from its usual orbit around the sun. The 33-foot-long (10-meter-long) "2024 PT5" will circle around Earth in a horseshoe path for two months, from this Sunday (Sept. 29) until Nov. 25, before the sun's gravity redirects it to its normal orbit in the Arjuna asteroid belt trailing our planet and orbiting the sun.

However, no near-Earth asteroid, including the soon-to-be "mini moon" 2024 PT5, is a threat to Earth for generations to come as far as we know right now. Based on long-term forecasts of asteroid orbits, NASA has ruled out any real risk of impact on our planet for at least the next 100 years.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social