See the moon meet Uranus in lunar occultation tonight (Nov. 8)

The lunar occultation of distant and faint ice giant Uranus will be visible from parts of Northern America and Asia.

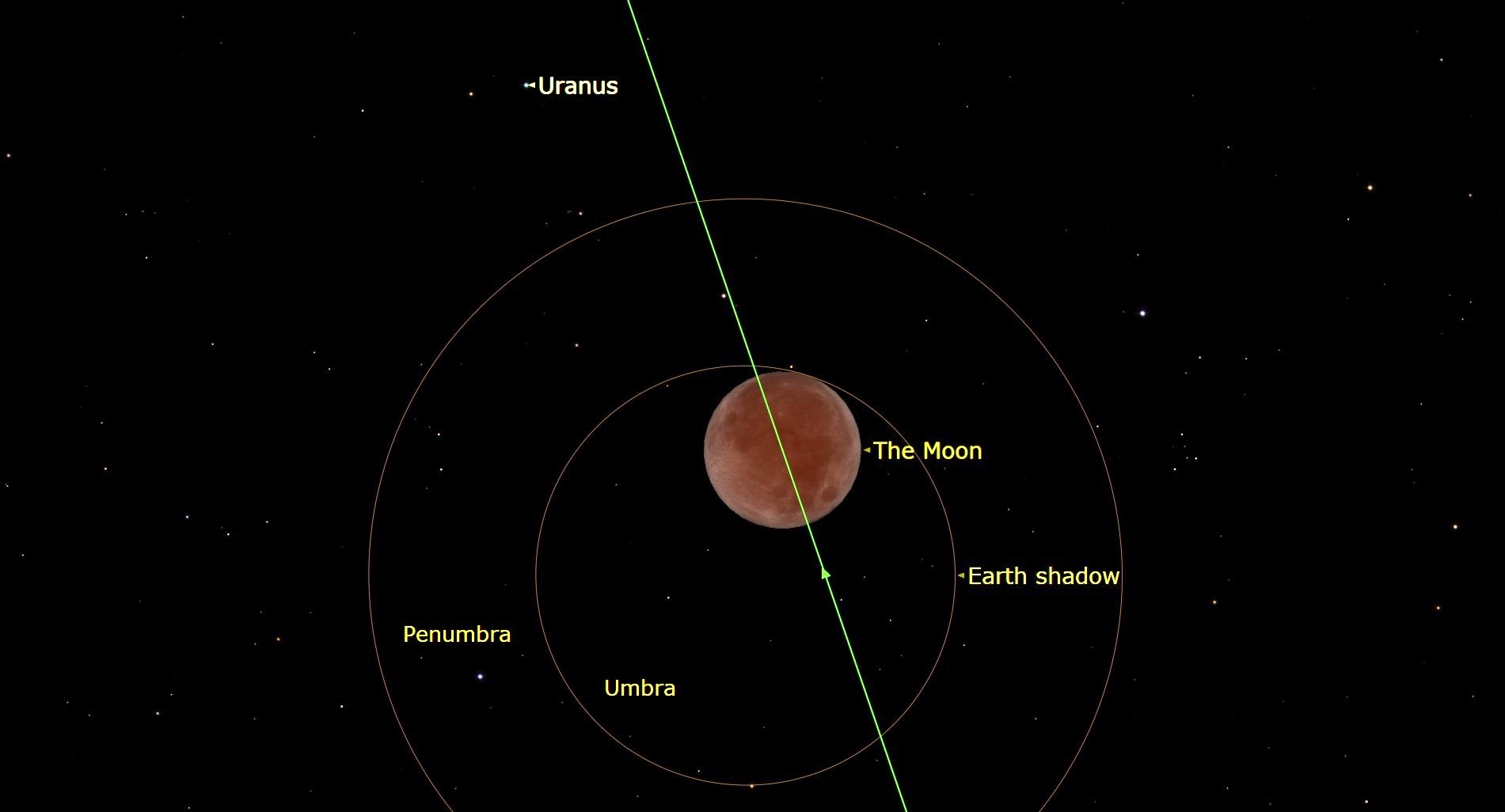

On Tuesday (Nov. 8), Uranus will disappear from the night sky for a brief period as the moon passes in front of the distant and faint ice giant planet. The event is what astronomers call a lunar occultation and it will be visible from northern America and parts of Asia.

The lunar occultation will start at 7:39 a.m. EST (1239 GMT) when Uranus — the seventh planet from the sun — begins to vanish behind the moon. As the lunar occultation begins Uranus will be in the constellation of Aries and will have a right ascension of 02h57m00s and declination of 16 degrees N, according to In the Sky.

As the ice giant planet vanishes behind the 14-day-old moon, Uranus will have a visual magnitude of 5.7. The Nov. 8 lunar occultation of Uranus won't be visible in New York City.

Related: What time is the Blood Moon total lunar eclipse on Nov. 8?

Think it's time to get a telescope to see the moon, Uranus, or any other celestial object close up? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Like all lunar occultations, the lunar occultation of Uranus will only be visible from a tiny fraction of the Earth's surface. This is because the moon is closer to Earth than other objects in the night sky like Uranus. Its proximity is close enough to mean that the moon's position in the sky depends on where on Earth's surface an observer is located.

As a result, as some skywatchers view the moon covering Uranus and hiding the ice giant from view, observers in other locations will see the pair separated by as much as two degrees, which is over four times the moon's diameter in the sky.

This means that even where the occultation is not visible the moon provides a decent guide to spotting Uranus in the sky.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In some areas of the planet, the lunar occultation won't be visible because Uranus is below the horizon at the time when it occurs. In other areas of the planet where Uranus is above the horizon, the occultation may still be unobservable because the sky is too bright for it to be seen.

Skywatchers hoping to spot the moon cover Uranus or the two-degree separation between the two will need a pair of binoculars to see the event and the planet.

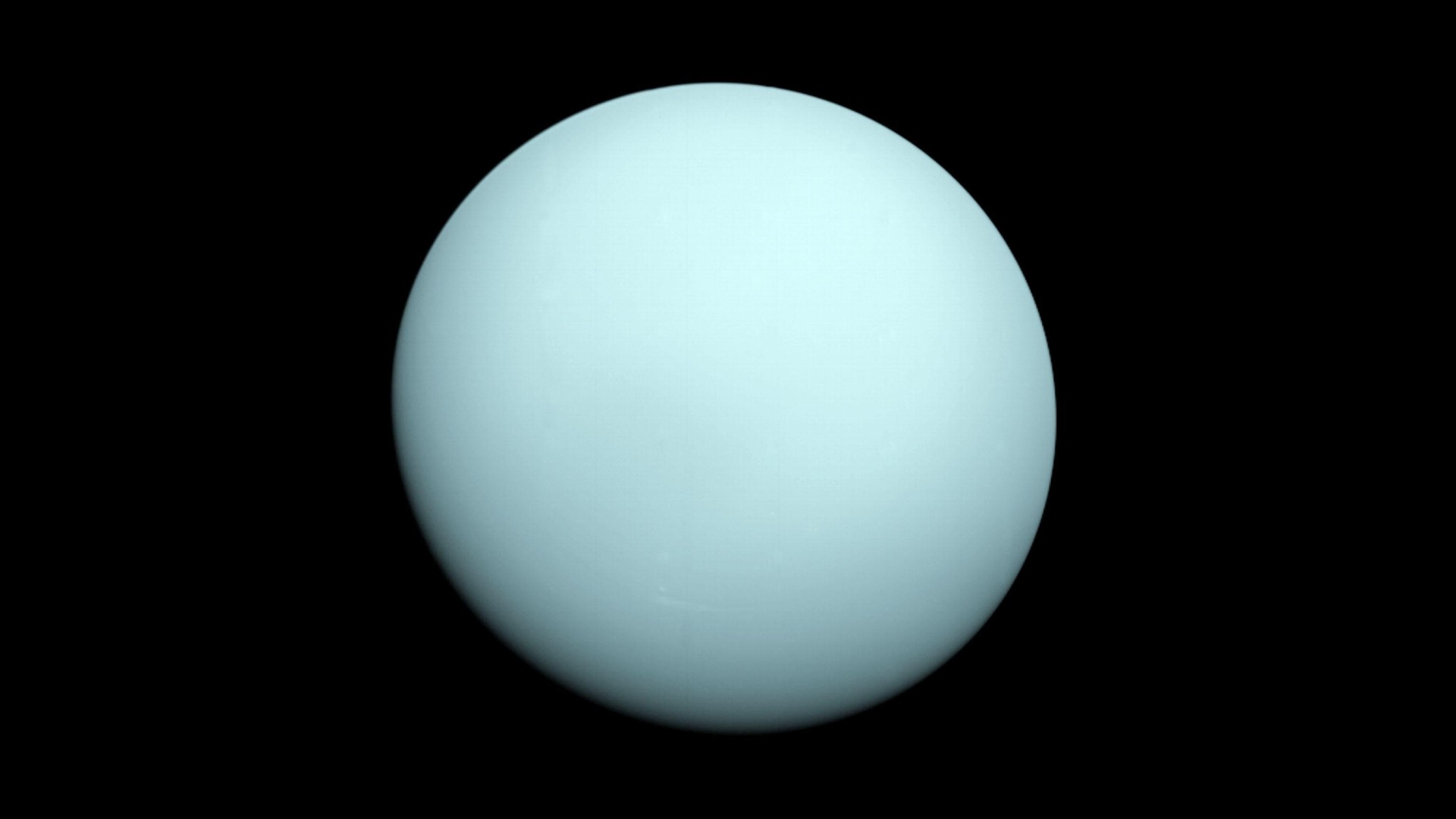

As the third largest planet in the solar system after the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus has a diameter that is four times wider than that of the Earth. As an ice giant world, at least 80% or more of the mass of Uranus is comprised of a frigid mix of water, methane and ammonia.

Despite being so large, Uranus isn't as visible as the solar system's gas giants because of its vast distance from Earth.

The ice giant is located at an average of around 1.7 billion miles (2.8 billion kilometers) from our planet. As the two planets orbit around the sun they never come closer than around 1.6 billion miles (2.6 billion km), and at their furthest from each other Earth and Uranus are separated by 1.98 billion miles (3.2 billion km).

Uranus is so far away from the sun that the planet takes around 84 Earth years to complete an orbit of the star.

Despite the fact that lunar occultations of Uranus are generally rare, the moon is on a roll when it comes to hiding the ice giant in the night sky. The moon has occulted Uranus from somewhere on Earth once a month since February this year and this streak will continue for the rest of 2022.

The next lunar occultation of Uranus happens on Dec. 5, and again will only be observable from certain areas on the planet.

Editor's Note: If you snap a photo of the moon and Uranus and would like to share it with Space.com’s readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.