'See you in orbit?' New book tackles the enduring dream of public spaceflight

Fancy plunking down cold, hard cash to launch your way into near-space heights, or snagging a ticket for a vacation in Earth orbit? Maybe you're still dreaming of that long-distance cruise out to the moon or beyond.

A space vacation has long been available only in the realm of science fiction, but this year, public space travel appears closer than ever before. British billionaire Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic, the company Blue Origin backed by Jeff Bezos (another billionaire) and the Mars-bound goals of Elon Musk and his ambitious SpaceX Starship are all pioneering different ways to bring space travel to the public.

But it's been a long haul to get reach this nexus of private (and public) space travel and a new book takes a look at just how long that voyage has been.

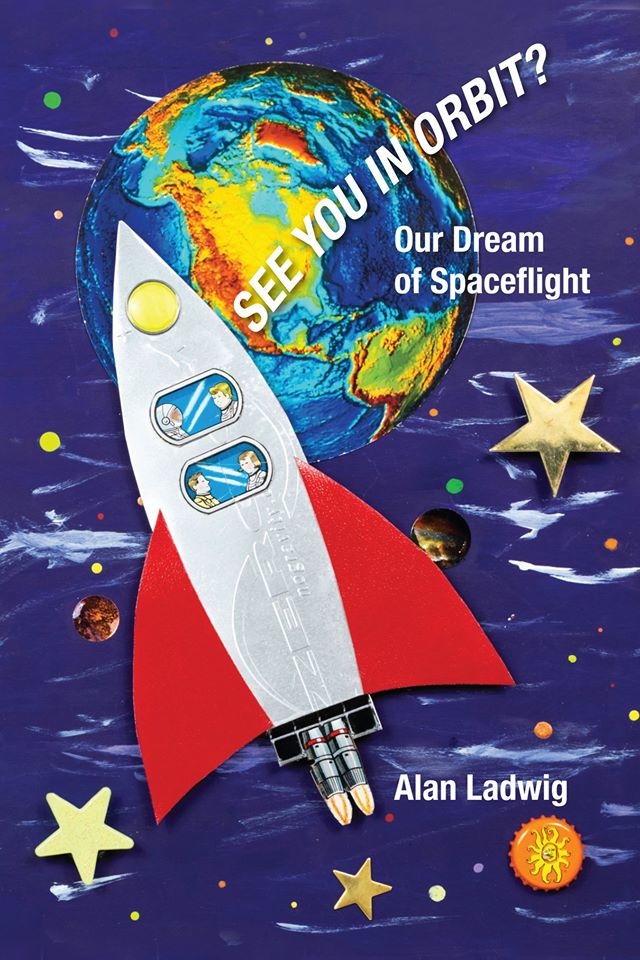

In "See You In Orbit? Our Dream Of Spaceflight" (To Orbit Productions, 2019), Alan Ladwig takes a look back at the missions and milestones in developing public spaceflight opportunities. Ladwig is a former NASA manager for both Shuttle Student Involvement Program and the Spaceflight Participant Program — which included the Teacher in Space and Journalist in Space competitions. He is now chief of To Orbit Productions, LLC, a consulting and art company, and he admits the new book has been a crime of passion for over three decades.

Space.com caught up with Ladwig to explore the historical quest for public space travel, tourism and the promise of one day strapping in and placing your table trays into locked position for liftoff.

See You In Orbit? Our Dream Of Spaceflight | $18 on Amazon

Alan Ladwig, a former NASA manager, dives into the promise of public spaceflight in this new book, which comes as Blue Origin, SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and more take aim at private and commercial space travel.

Space.com: Your book has been 30 years in the making. Why so?

Ladwig: I started it in 1990 and when I began the whole notion of citizen space travel as a reality was pretty far away. There wasn't a good way to have an ending that gave people much hope. You had some companies that came to NASA wanting to outfit the shuttle with a passenger module in the cargo bay. Other organizations wanted to build their own spacecraft. But none of that ever panned out. Most of them were undercapitalized and didn't have the money to pull it off. Or their business model was just not accurate enough to be sustainable.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: And you feel that's changed?

Ladwig: History is full of people that came through with good ideas and just couldn't quite get to the finishing line. I put them in my hall of fame for having tried and trying to keep the dream alive. So it took years to get to this new breed of advocacy investors that had the wherewithal, the technical expertise, but not necessarily operational experience at the beginning.

Space.com: You have a cautionary question mark in the title of your book. How come?

Ladwig: Even now that we're on the precipice of suborbital flight, hopefully this year, look how long that’s taken. Once again, though we're getting closer to the reality, the expectations and the predictions have been off by quite a bit.

Space.com: But over the years, the public remained ready to buckle up?

Ladwig: As I say in the book, that’s because for the last 70 years we were told we were going to get to go … told by industry, by the government, by visionaries, and by the media. Arthur Clarke, a year before Apollo 11 said we’ll be able to fly to the moon as cheaply as you can fly from New York to Tokyo. It got written down as though it was gospel. And I think now you've got a similar thing going on with Elon Musk sending people to Mars by 2025, or circumlunar flight even earlier. He said that he has "aspirational" goals, and I love that term. It's kind of an overall caveat that protects him from not delivering. But sooner or later you've got to deliver. If you don't people start to get a little cynical.

Space.com: I was drawn to your behind-the-scenes account of the loss of Challenger and its crew that included teacher-in-space, Christa McAuliffe. You subtitled that section "The Dream Turns into Heartbreak."

Ladwig: Because of the accident my emotions were all over the place. Having a civilian onboard had nothing to do with the accident. In the beginning, the Spaceflight Participant program was projected to possibly do a flight three to four times a year. We had been considering journalist in space and artist in space too.

My favorite line in the countless letters I received from people eager to fly: "Look no further, I'm the one." After the accident that put it all on hold.

Space.com: Jumping to today, just how on edge is public space travel? Is it resilient enough to survive another accident?

Ladwig: I think it will depend on how far along we are in flight that an accident happens. Also, it depends on what caused the accident. If it occurs early on it could be a setback for the commercial companies. But if it happens three or four years from now and it's a private citizen, I don't think the public reaction will be the same as when astronauts have died in the past.

It's like climbing the Himalayans. Look how many people die in the Himalayans and that hasn't stopped people from going. But I do think that's the kind of discussion people will have should there be an accident. Any endeavor of going forward on ambitious or adventurous things there could be death, and that’s part of it.

Space.com: Do you think public space travel is simply an extension of how passenger air travel has evolved over time?

Ladwig: Professor Patrick Collins is a well-known and respected authority on space economics and space tourism. He noted in his research that in the first 100 years of aviation, passenger travel grew from zero in 1901 to 1.5 billion passengers in 2001. Meanwhile, the first 50 years of human spaceflight, fewer than 600 individuals achieved a rocket ride. So those comparisons are made periodically. And there are those who suggest that space should have done the same thing, but others that say it's much more difficult to make that transition to space.

But early on you saw people from the aviation industry talk about how this was going to be a natural progression, even for their own companies. Again, it was the expectation raised in the public because this is what they were being told.

By the way, Collins had different phases of space travel with dollars attached: Pioneering Phase, Exclusive Phase, the Mature Phase and the Mass Market Phase. I think it's a good model for today.

Space.com: What's your take on the recent Space Adventures/SpaceX agreement to launch citizens into space?

Ladwig: The recent announcement that Space Adventures will be a ticket agent for flights on SpaceX's Dragon2 is an exciting milestone toward the dream of spaceflight. While the expected ticket price remains beyond the reach of all but the wealthiest of citizens, the collaboration represents an important step to open space travel beyond the traditional astronaut corps.

The announced projections of flights by 2022 may be optimistic. However, once service begins, the aspirational goal will quickly fade in the public's memory.

Space.com: What should a civilian space tourist expect from his/her flight?

Ladwig: From an Earth orbiting perspective, there's the Frank White Overview Effect. That part is going to be tougher to do on a suborbital flight. So my answer would be initially the tourism part is more experiential. It's not destination-based, it’s experiential … the experience of enjoying microgravity and that floating sensation.

For the suborbital flights, it appears that individuals will get anywhere from six to eight minutes of weightlessness. Will that be a transformational experience remains to be seen. I just don't think we know enough about it at this point. And that's a challenge for the companies offering this service. Will people come back feeling it was worth it? I'm betting that they are going to enjoy it. But will people come back and say it wasn't worth a quarter million dollars?

Space.com: And you have to be fit and slim to wear those spacesuits!

Ladwig: Everybody talks about the democratization of space. If that's truly going to be fulfilled, it's not going to be by just a bunch of svelte people. There's a pretty diverse range of people that want to have the experience. You have to take on all comers.

Space.com: What are your take home messages in the book?

Ladwig: The dream has been around for decades…even centuries. It's part of our mythology, as early as 1865 when Jules Verne wrote "From the Earth to the Moon." The motivations have been consistent, certainly since the 1920s.

Another point is why people think that they are going to go. It’s because we’ve been told that’s the case for a long time. We’ve been told our ticket to ride was just a rocket away.

The Holy Grail has been launch costs coming down enough that anybody could afford it. I think unless something radical happens with the cost to orbit coming down, it’s a long time before you reach a mass market stage. We probably will some day, but who knows when that’s going to be.

I'm no longer interested in the predictions ...I want to start seeing the reality. You don't want to be negative but you want to be realistic.

Leonard David is author of the recently released book, "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.