Ex-NASA scientist dishes on space food in new memoir 'Space Bites'

"There are a bunch of people out there who think, 'Oh, it is horrible. There is nothing enjoyable about it at all.' That's not true."

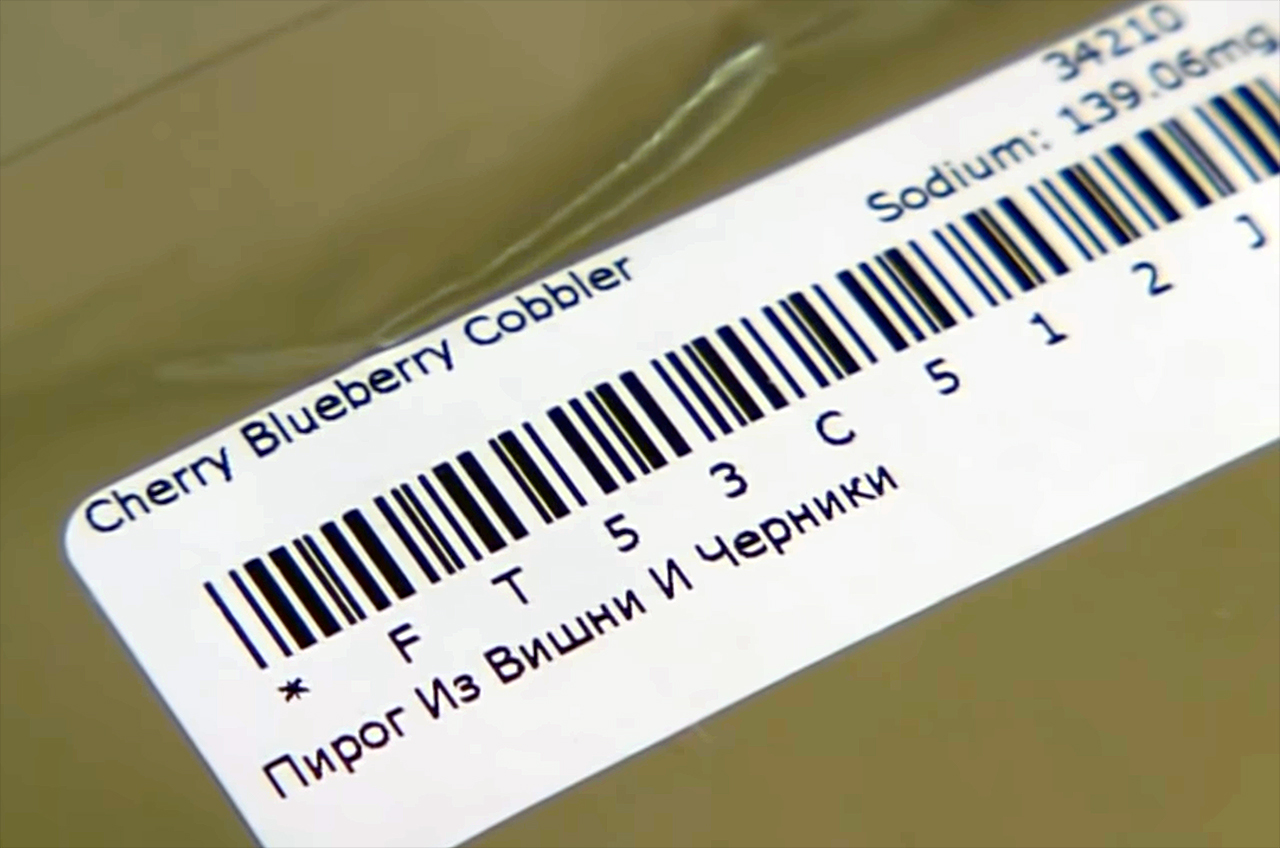

Of all of the freeze-dried, thermostablized and off-the-shelf food items that she helped send into space, Vickie Kloeris' personal favorite was the cherry-blueberry cobbler.

A food scientist at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston for 34 years, Kloeris not only enjoyed the cobbler, but helped to develop it.

"During the shuttle program, we really weren't doing any product development. All we were doing was, if a product went away, we would find a commercial product to replace it," she said in an interview with collectSPACE.com. "It wasn't until we got into the International Space Station [program] that we finally got the funding to develop some products, and the first thing that came up was desserts."

More than just a desire to satisfy astronauts' sweet tooths, Kloeris and her team in the Space Food Systems Laboratory felt there were benefits to adding desserts to the crew members' menus.

"We really thought that, from the psychological perspective, having a dessert that you could warm up would be great. And they were; they were highly accepted."

Plus, the cherry-blueberry cobbler was just "really, really good."

Related: Food in space: What do astronauts eat?

Kloeris shares more details about the desserts' development and more anecdotes from her NASA career in her newly released memoir, "Space Bites: Reflections of a NASA Food Scientist," published by Ballast Books.

collectSPACE spoke with Kloeris about the book, space food and the challenges facing her successors as commercial spaceflight expands and astronauts embark on longer space missions. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

collectSPACE (cS): So we know what was your favorite, but what was your least favorite food item that you sent into space?

Vickie Kloeris: I guess for me, just personally, it was the split pea soup. I'm not a pea person.

The thing about the split pea soup — it was in a pouch. And because it was in a pouch, it had to have a certain level of viscosity. It had to be pretty thick. And so not only was it peas, which I didn't like, but it was really thick. So that was my least favorite.

cS: As you explain in "Space Bites," some foods are just not a good match for the microgravity environment of space. You write about why tortillas are the perfect bread for spaceflight, which is the same reason potato chips are not a good idea — crumbs (or the lack thereof). But when you mention an attempt at flying chips in cans, you refer to them generically, rather than as Pringles. Is that just a force of habit, given NASA's aversion to referring to foods by their brand names?

Kloeris: It was definitely Pringles that I was talking about, but, yeah, it was a force of habit that I didn't identify the brand name.

We used to joke about it. The fact that M&M's are called "candy coated chocolates" goes back to before my tenure, but more than once I got asked, "Do you erase all the little m's off the candy?" [No.] But for most of my career with NASA, "commercialization" was a dirty word. Now the pendulum has swung far in the opposite direction.

Now the agency's overall goal is, how can we commercialize? And it is interesting to see that has not yet drifted down to the food system. For instance, Axiom Space's third private mission to the space station is about to fly a Thai product, and that was done through an agreement between three different companies. NASA still is not in a position where it would consider something like that.

Related: Private space station: How Axiom Space plans to build its orbital outpost

cS: You recall in "Space Bites" about how, early in your career, you were tasked with cleaning out a closet and discovering all this leftover food — space food cubes — from the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs. You not only cleaned it out, but tasted some of them. Was that the oldest example of space food you've eaten?

Kloeris: The cubes were probably the oldest space food I ate, and they were pretty awful.

cS: There are space food packages that you prepared that are now in private and museum collections. Would you recommend someone trying to eat them?

Kloeris: It depends on how and where it was stored, because the pouch material that NASA has been using for freeze-dried foods is not totally impervious to moisture. We used an overwrap with a foil layer to keep the moisture out aboard the space station. But if you had a freeze-dried package that had been sitting out on display for a long period of time, in theory, it could pick up moisture, and the freeze-dried foods are not sterile; there is bacteria in there.

We tested the cube packages before eating them to make sure there were no pathogens.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

cS: Is bacteria or pathogens a concern for future, longer-duration missions, such as when we send astronauts to Mars?

Kloeris: What's interesting about NASA's Artemis program is the food system is actually going to be a step backwards. This could change, but the latest that I've heard is that they will not have the capacity to heat food on the Artemis vehicles.

But for Mars, shelf life is definitely the biggest challenge. I touch on this in the last chapter of the book, but having to most likely pre-position the food for a Mars mission — having to produce it, put it on a cargo rocket and send it Mars — by the time the crew eats it, it is going to be really old. It could be anything from five to seven years old, potentially, depending on how they pre-position the food and when they pre-position.

We can make food that is safe to eat for that length of time. The challenge is going to be what kind of nutritional content it will still have, because while freeze-drying and thermostabilization controls microbial growth, it cannot really stop the chemical changes in the food. Over time, chemical changes are going to cause the nutrition to decline, especially with certain nutrients.

And quality degrades. So color, flavor and texture. After a while, if the quality is poor enough, the astronauts will eat only enough to survive and not really enough to thrive. So that's a challenge, because NASA wants high-performing crew members throughout a three-year Mars mission or however long it's going to wind up being. That's the biggest challenge.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2023 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.

Rooms and a view | Space photo of the day for May 6, 2025

NASA astronauts prep ISS for new solar arrays on 5th-ever all-female spacewalk