This astronomer found a sneaky extra star in James Webb Space Telescope data

"At some point, I had looked enough into the literature to know that this is real."

While sitting in his office, Naman Bajaj stared at the precious data that led to the final installment of his trio of published papers, each of which incrementally answers a very loaded question: Why do some planet-forming disks creep onto their own stars? The three studies were robust, interesting — and most importantly, finished. But before closing the door on these last few data points, delivered by the famous James Webb Space Telescope, Bajaj decided to wring them for all they were worth. He certainly didn't expect, however, to open yet another door.

"My advisor was gone for a conference or something for a month; I was just playing with the data and saying, 'What more I can do? Is there anything more that this data can tell us?'" Bajaj, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, told Space.com.

Soon, he would make a brilliant find. One of the star subjects he and his collaborators already spent so much time with was actually a double; it's just that no one had noticed. The cosmos, we're constantly reminded, is big enough that something as incomprehensibly huge as a pair of stars waltzing around one another can be missed. "One pixel in this image that we are looking at is 14 AU," Bajaj said. For context, a single AU, or "astronomical unit," represents the mind-blowing distance between our planet and the sun — about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers). In a way, it is remarkable that a human can make this discovery at all.

The paper trail

To understand how Bajaj arrived at his conclusion, recall those first three papers. All three concerned the dynamics of matter-filled disks around stars. It is within these disks that planets can blossom from rocky or gassy seeds, which is why they're so interesting to scientists. More specifically, Bajaj and his team were scratching their heads about how material from those disks can sometimes fall onto the stars anchoring them. It is something of a mystery why this happens.

"For example," Bajaj said, "The Earth is going around the sun, but it's not falling onto the sun because it's constantly going around in that orbit." According to the laws of physics laid out by Isaac Newton, if the orbit of an object isn't interrupted, it shouldn't just start changing its trajectory. So, the team reasoned, maybe something is disturbing such inward-falling disks and they're not acting on their own. It would all make sense if the disks lost some angular momentum, for instance — but to do that, they'd perhaps need to lose some of their masses. So, how would that mass loss happen?

This is the basic question Bajaj and fellow researchers set out to answer.

In a nutshell, the team's first paper confirmed that strong "winds" could be moving material from the disk vertically upward. The second paper was meant to calculate how much material zooms away through jets shooting out from the disks, which are similar to the winds but far faster and narrower. The third paper, meanwhile, was pretty much meant to connect the first two, comparing mass loss through winds with mass loss through jets. But Bajaj saw something fishy in his final dataset.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

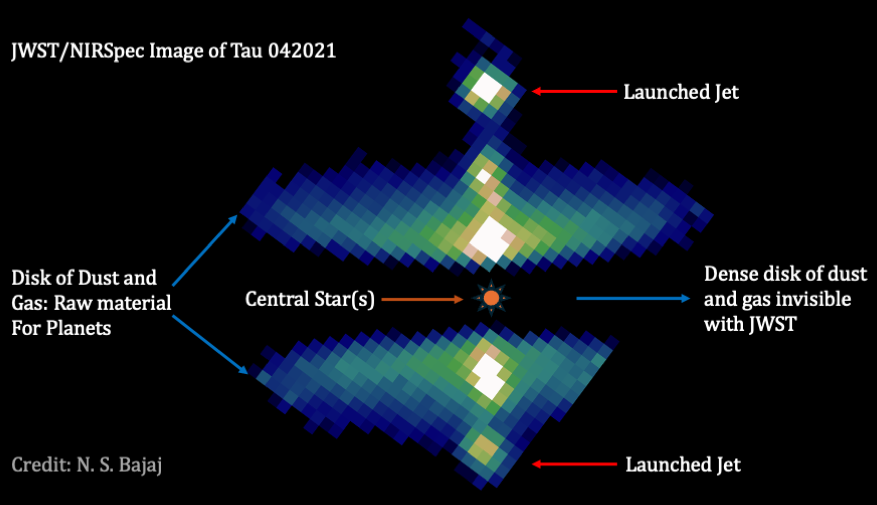

His team's work about the high-energy disk-related jets was based on four star candidates in the Taurus star-forming region, which sits about 457 light-years from Earth — and one of these candidates had a jet that kind of looked … too perfect? It's called TAU 042021.

"This one particular object stuck out because it was so symmetric — it's probably the best case of jet symmetry that we have seen so far, I would think," he said. "The only way you can explain this sort of symmetry is with a binary."

The symmetry speaks for itself

In this case, the term "symmetry" is used in reference to the two lobes of a jet sprouting from an object — the lobe above the object and the lobe below it— syncing up with one another.

"If the two sides of the lobe have nothing to do with each other, like they move randomly, then it doesn't tell you anything — it's probably because of the surrounding medium," Bajaj said. "But when you find some sort of symmetry, or even anti-symmetry for that matter, it is telling you something more."

"If anything is happening to the disk itself, what you will see is a point-like symmetry," Bajaj added. "They will always be exactly opposite of each other, essentially — but what happens when you have a binary?"

What this specific symmetry told Bajaj is the jet he was seeing associated with TAU 042021 was most likely not even coming from the star's planetary disk at all. It was probably blasting out from another star orbiting around the original.

"My first reaction was, 'Oh, this is awesome,'" Bajaj said. "This technically would be my own sort of first discovery in a sense, so I was very excited — but at the same time, I was like: 'But what do I know?'"

The next step, of course, was to test his hypothesis as much as possible; he decided to use models of known binaries to make sure everything checked out. And, well, it did: "At some point, I had looked enough into the literature to know that this is real."

Stellar specs

The fact that Bajaj was looking at a one-pixel-to-14-AU ratio in his dataset, combined with the fact that both stars in the newly found binary are infants that haven't started their core nuclear fusion processes — there's not a ton we know about the stellar subjects. We do know a little, though.

For instance, we know that the stars are separated by a distance of 1.35 AU, which is actually quite close in astronomical terms. If you can picture it, that means the two stars are only a little farther apart than Earth and the sun. We also know that the mass of one of the stars should be about 0.33 solar masses while the other should be about 0.07 solar masses. Remember, they're baby stars, so it's not like two sun-size objects are sitting that close together. And, fascinatingly, Bajaj resolved that the disk around the system is really (really) thick — up to 250 AU in micron-size dust grains. "This corresponds to nearly 27,000 times the diameter of the sun," he remarked. Meanwhile, the diameter of the disk is estimated to reach up to 500 AU. For context, the distance from the sun to the end of the Kuiper Belt that extends far beyond Neptune is only about 50 AU.

"Even in cases of binaries, for this particular mass of the star, I think it's still an outlier," Bajaj said of the huge disk.

This little bit of information might also be enough to ruffle some research going on in the astronomy community.

"I think that the first reaction will be, 'Oh, that's so cool,'" Bajaj said. "And then the second reaction will be 'Oh, we're doomed. Our research is doomed.'"

That's because the object TAU 042021 is quite well-studied among physicists, including through James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) imagery. That's because, serendipitously, Earth's position in space allows us to view the star's disk edge-on. Imagine holding a dinner plate in front of you, if the side of the plate is eye-level with you, you're looking at it edge-on.

This is a huge advantage, because stars can get very (very) bright. "Irrespective of how sensitive your instrument is, you can still look at this," Bajaj said. "Sometimes the star is too bright, so we cannot observe it with great instruments like the JWST — but here, that's not the case. Here, the star is not hampering our ability at all."

Additionally, the disk associated with TAU 042021 was considered particularly large even before Bajaj even learned of the system's binary nature.

"There have been multiple studies with JWST, and, yes, they will be impacted," Bajaj said. "A lot of them are about modeling what is happening at the disk."

If you're trying to model the disk's evolution or behavior, he explained, then it's crucial to know whether there is one star or two stars at the center. He also points out that there's likely a larger gap between the central stellar area and the start of the inner section of the disk than previously anticipated. "In their models," he said, "the disk will start at 1.2 AU, but now the disk has to start out at 4 AU. So that is a big gap right there, and that will lead to so many different things."

Amid that possible chaos, Bajaj hopes to continue looking at the dataset he once thought he was finally ready to move on from. He's looking into the intricacies of the other three star subjects, and has a sneaky hunch about one of them also being a surprise binary. He's also interested in learning about whether there could be more than one jet in the TAU 042021 system, perhaps one coming from each star at its center, and is trying to figure out if NASA's recently launched SPHEREx space telescope can help out with that. The questions are endless, and it bears remembering it is these strings of thought the James Webb Space Telescope was built to inspire in the first place. It really has lived up to its promise.

As Bajaj puts it: "These James Webb Space Telescope data sets are so beautiful."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.