This star burped after eating a planet — but the planet was really asking for it

The planet "splashed down" into the star, sending a giant plume of gas into space that gave the star a ring.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has been studying the scene of a dramatic collision between a star and its planet, but whereas astronomers had originally thought that the star was a red giant that engulfed the planet, the JWST has found a very different story: The planet crashed into the star.

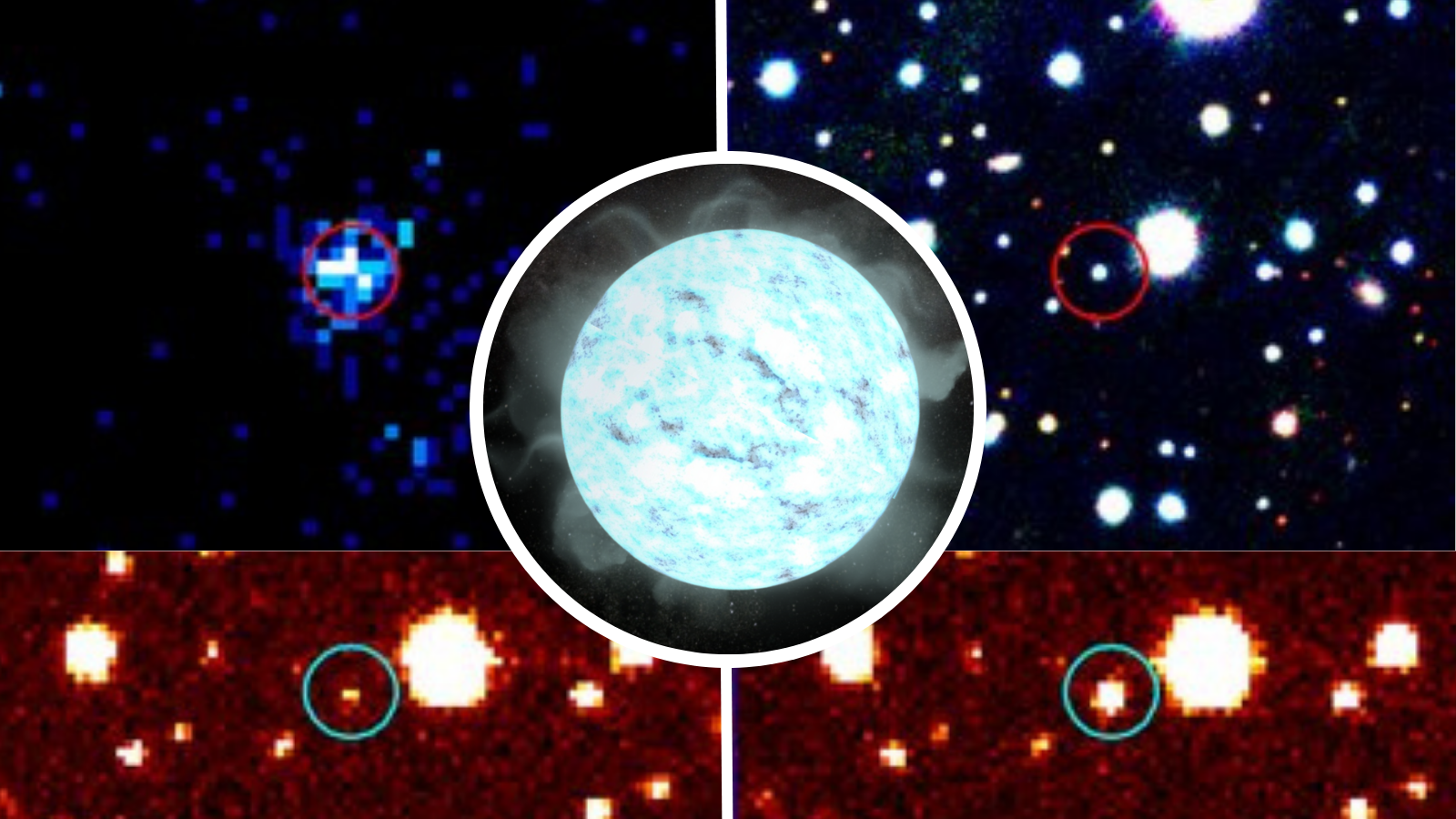

In 2020, the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory in California spotted a distant star — that sits about 12,000 light-years away from us — suddenly brighten in the night sky. When looking back at the star in archival data from NASA's NEOWISE mission, astronomers found that the star, designated ZTF SLRN-2020, had been brightening in infrared light for a year before the optical flash.

A study from 2023 concluded that ZTF SLRN-2020 was an evolved sun-like star called a "red giant" that had expanded, in the process engulfing a gas giant planet orbiting around it. The flash of light was then interpreted as the planet being destroyed as it was consumed by the growing red giant; the infrared brightening was believed to be caused by dust left over as the planet effectively burned up in the red giant's atmosphere, much like a giant meteor.

However, a team led by Ryan Lau of the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab in Tucson, Arizona, chose to take a closer look at ZTF SLRN-2020 using the JWST.

"Because this is such a novel event, we didn't quite know what to expect when we decided to point this telescope in its direction," said Lau in a statement. "With its high-resolution look in the infrared, we are learning valuable insights about the final fates of planetary systems, possibly including our own."

What Lau's team found was a surprise: The star wasn't bright enough to be a red giant. Instead, it looked like a "regular" star with about 70% of the mass of our sun. This, of course, changes the story of ZTF SLRN-2020. If the planet in this system wasn't consumed by a red giant, then the opposite is the only explanation: The planet must have crashed into the star instead.

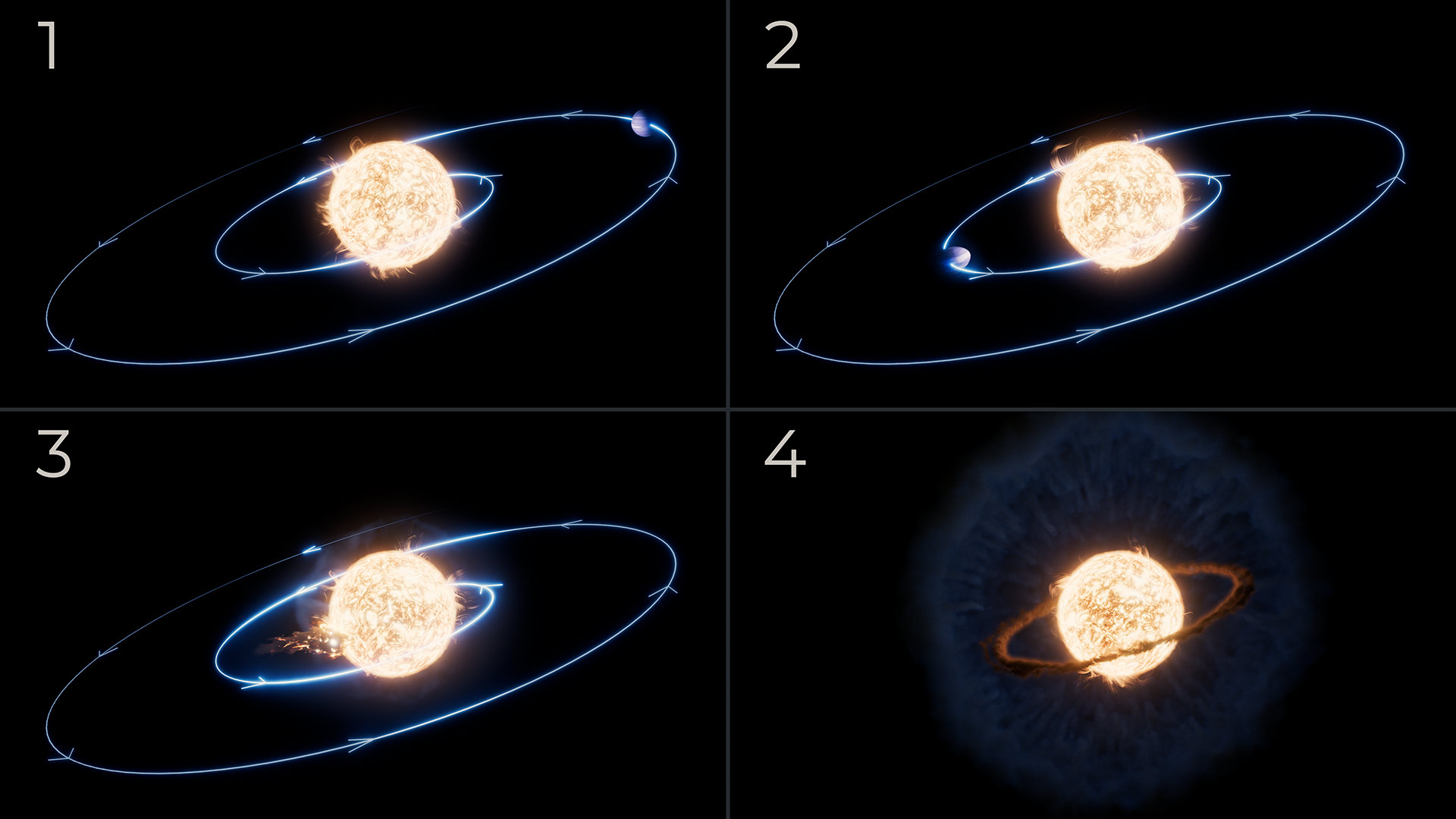

How can this happen? Well, right from the very first exoplanet discoveries, astronomers have been finding bizarre worlds called hot Jupiters. These are gas giants that formed far from their star and then migrated inwards. This particular planet must have migrated so close to its parent star that, over time, gravitational tides began to pull the planet inexorably to its doom.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The planet eventually started to graze the star's atmosphere. Then it was a runaway process of falling in faster from that moment," said Morgan MacLeod of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "The planet, as it's falling in, started to sort of smear around the star."

The tidal forces began to stretch the planet in a vice-like grip, until finally the planet "splashed down" into the gases of the star, and as the star swallowed the planet it belched out a tidal wave of gas into space. This ejected plume cooled and condensed into a cloud of gas, instigating the infrared brightening seen by NEOWISE.

But there was one more surprise. Astronomers had expected to see an amorphous cloud of gas, but the JWST's Near-Infrared Spectrometer instead found a disk of molecular gas encircling the star at close proximity. The disk looks for all the world like a miniature planet-forming disk.

"I could not have expected seeing what has the characteristics of a planet-forming region, even though planets are not forming here, in the aftermath of an engulfment," exoplanet astronomer Colette Salyk of Vassar College in New York said in the statement.

The disk is thought to be composed of some of the ejected gas plume that fell back towards the star, but the details are still sketchy. However, given that this is only the first of hopefully many similar planet-star collision events to be observed, it may be that we'll find the answers in another doomsday system. The in-depth, wide-field surveys of the forthcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory (which sees first light this year) and NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope are expected to find many other similar events that astronomers can follow up on with the JWST.

The results were published on April 10 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.