Monocular vs binocular: Which is best for stargazing

From magnification to light-gathering, here’s how to make the decision between buying binoculars or a monocular for stargazing and astronomy.

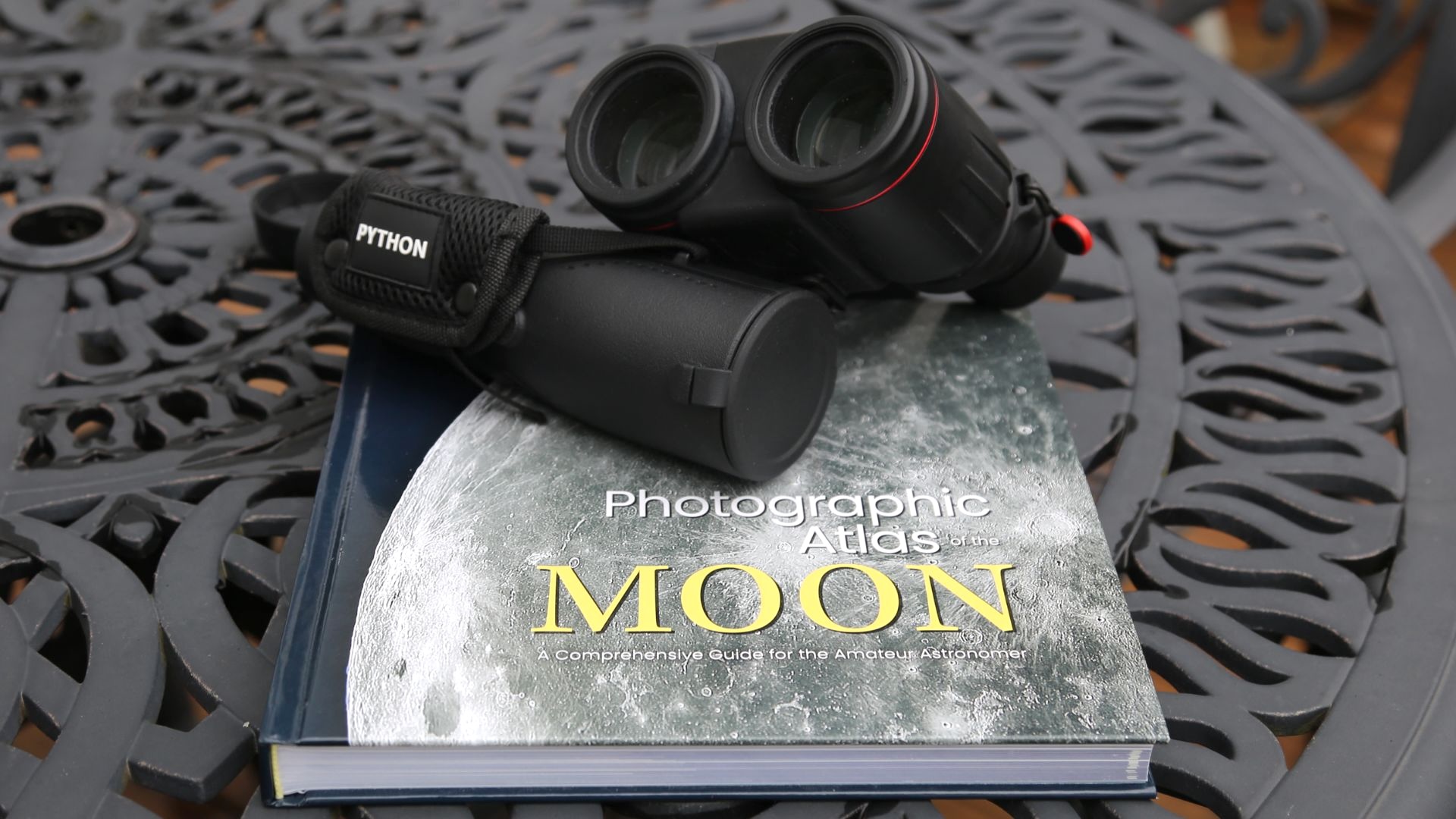

Why are you carrying around a bulky pair of binoculars for stargazing when you could be packing a monocular and doing away with half the bulk? If you’ve been on the road lately – whether traveling, hiking or camping – and decided to leave your heavy binoculars at home, you’ve likely considered investing in a monocular.

But is it possible to choose between the best binoculars and monoculars for stargazing? Despite weighing about half what a pair of binoculars can, is a monocular a good substitute for stargazing and astronomy? Which is better for watching the night sky, a monocular or binoculars?

Both have their uses, but there are differences you need to know about before making that all-important purchasing decision. Here’s everything you need to know about comparing binoculars and a monocular for stargazing and astronomy.

Similarities between binoculars and monoculars for stargazing

Both monoculars and binoculars are great for studying the moon and brighter celestial objects. Although you won’t see much detail, if any, from the planets, it’s easily possible to see Jupiter's moons using monoculars or binoculars.

A good monocular or binocular for astronomy will have more or less the same specifications. Every binocular and monocular is sold with two numbers prominently displayed, such as 8x42. That refers to 8x magnification and 42mm diameter objective lenses. For looking at the night sky, choose at least 10x42, preferably 10x50, which keeps the magnification low enough to easily navigate the night sky while allowing enough light in at night.

Magnification comes in handy — you’ll get a good look at the lunar surface and the Jovian moons — but it adds hugely to the weight of both a monocular and binoculars. Magnification means a narrower field of view, but which can make smaller deep-sky objects harder to find, such as the Pleiades (M45), the Perseus Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884) and the Andromeda Galaxy (M31).

Differences between binoculars and monoculars for stargazing

If your priority is portability, you may be tempted to compare any bulky pair of binoculars with any small, sleek, pocket-sized monoculars. Don’t do that. Asking which is better — a monocular or binoculars — is the wrong question because both have pros and cons for stargazing.

Doing astronomy means collecting lots of light. While it’s mostly down to the aperture of the optic, ED (short for extra-low dispersion), glass better transmits light, while multi-coated lenses reduce glare. You can get both of these features on both binoculars and monoculars. However, while the market for binoculars is mature and has plenty of choice, that’s not true of the monocular market, which is changing quickly but is less dependable. So, while it’s now difficult to buy a terrible pair of binoculars, it’s still possible to buy a bad monocular.

When would a binocular be better for stargazing?

Binoculars are better for longer stargazing sessions and a detailed night sky exploration and are best suited to those who don’t mind a slight learning curve. The way binoculars work, looking with two eyes instead of one heightens the experience, creates more immersion in the night sky and reduces eyestrain (because you don’t have to scrunch one eye shut).

The added weight can make it tricky to hold binoculars steady, but that does give you options. One technique here is to observe objects high above you, allowing the binoculars to be supported by your face. Another is to use your forearms as scaffolding, with elbows drawn into the chest. Either way, the added bulk of binoculars makes them best for use with a shoulder bag or camera bag.

When would a monocular be better for stargazing?

A monocular is an ideal gadget in a backpack or the glove box of a car, and it can be used by anyone immediately. It’s handy in emergencies and valuable for grabbing a quick close-up of the moon, the moons of Jupiter or bright deep sky objects while on camping or driving trips where portability is critical.

A monocular is easier to set up and use than binoculars, which are slightly more complex because the distance between the two eyepieces is essential to keep a single image. It’s also necessary to focus both eyepieces to match your eyes.

That’s not the case for a monocular. The way monoculars work, they merely requires one eyepiece to be focused. Monoculars are more difficult to hold still than binoculars if you hold them with a hand, so you use two hands – one in front of the other – to keep them steady.

Price comparisons

Generally speaking, monoculars are about half the price of binoculars, but that becomes more obvious because they’re typically smaller.

A good example of what to expect is Hawke’s Endurance ED range, which includes monoculars from 8x25 to 10x42 and binoculars from 8x32 to 12x50. The 10x42 monocular costs $145/£122, and the 10x42 binocular costs $249/£279. We tested the Hawke Endurance ED 10x42 monocular and gave it 4/5 stars due to its fog- and waterproofing, the clear and bright images it produced and good close-focusing ability (down to six feet / two meters).

It’s relatively rare to find a monocular above 12x50 from a major brand — most come with smartphone adaptors and tend to be for wildlife — but binoculars are sold in much larger, astronomy-centred sizes, such as the great-value Celestron SkyMaster Pro 15x70.

It’s also more common to find high-end optical features on binoculars, such as the Nikon Monarch HG 10x42 ($979/1,159), which has a Field Flattener Lens System to create a sharp and clear view around the lens periphery.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jamie is an experienced science, technology and travel journalist and stargazer who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com and author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, and is a senior contributor at Forbes. His special skill is turning tech-babble into plain English.