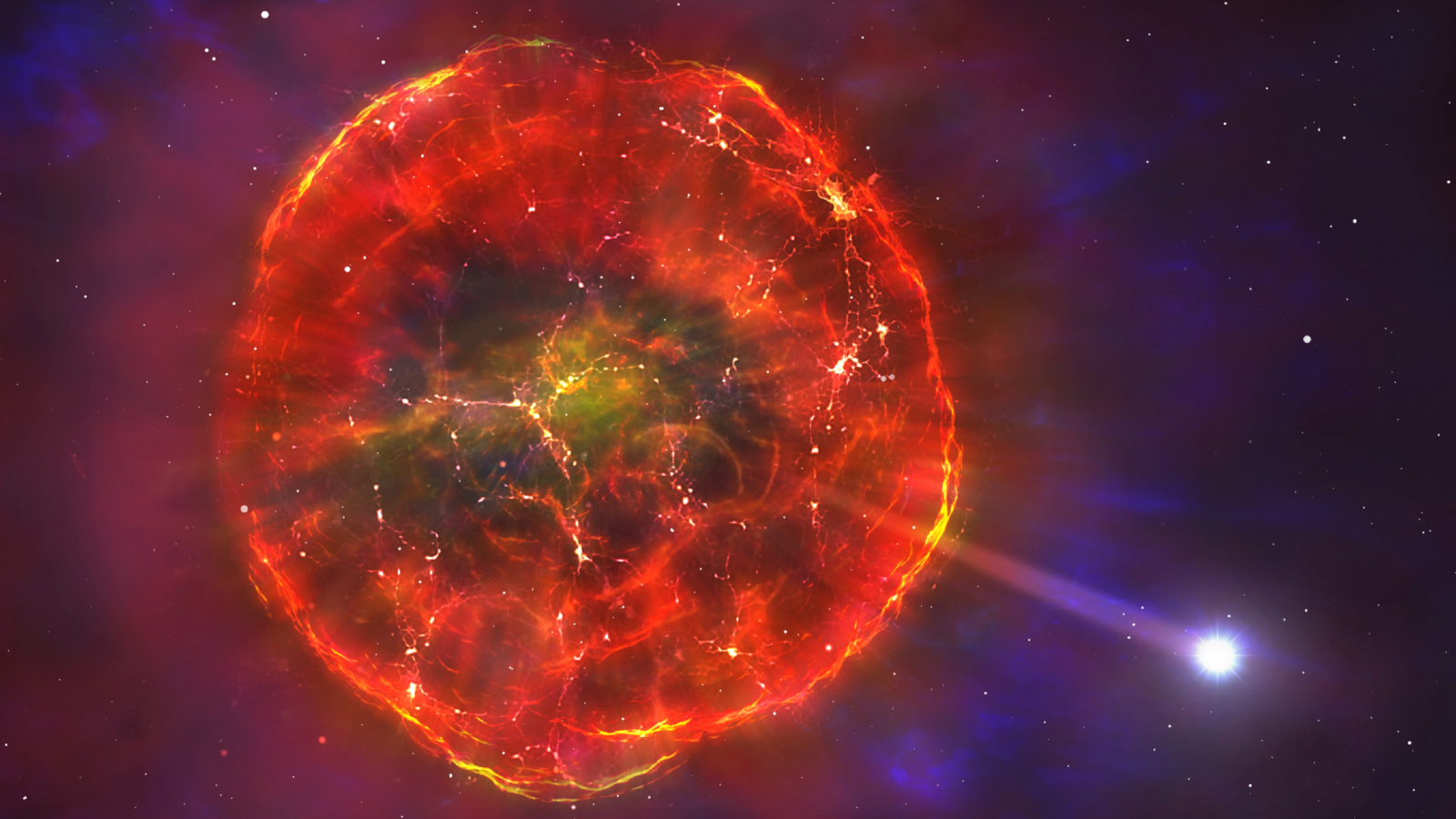

1st supernovas may have flooded the early universe with water — making life possible just 100 million years after the Big Bang

A new study suggests that the explosive deaths of the universe's earliest stars created surprising quantities of water that may have sparked extraterrestrial life in the very first galaxies.

When the cosmos' first stars exploded in spectacular supernovas, they may have unleashed enormous amounts of water that flooded the early universe — and potentially made life possible just millions of years after the Big Bang, new simulations suggest.

However, this theory clashes with our current understanding of cosmic evolution and will be extremely difficult to prove.

Water is one of the most abundant compounds in the universe, according to NASA. Aside from Earth, astronomers have found water in several places throughout the solar system, including scattered above and below the surface of Mars, inside the ice caps of Mercury, surrounding the shells of comets and buried in underground oceans on several major moons. Outside our cosmic neighborhood, researchers have also detected water on distant exoplanets and within massive clouds of interstellar gas that permeate the Milky Way.

Until now, scientists assumed that all this water gradually built up over billions of years as hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, combined with oxygen that has been forged in the hearts of stars and expelled via supernovas. But in the new study, uploaded Jan. 9 to the preprint server arXiv, researchers simulated the explosive deaths of giant, short-lived early stars — which each had a mass equivalent to around 200 suns — and found that they could create the conditions needed for water to take shape.

The water from these stellar explosions would likely have formed at the hearts of dense clouds of hydrogen, oxygen and other elements left behind by stars. It may have had concentrations up to 30 times higher than the water seen floating in interstellar space within the Milky Way, the researchers wrote in the study, which has not been peer-reviewed yet.

Related: Could a supernova ever destroy Earth?

If correct, the new findings would have big implications for scientists' understanding of galaxy evolution and extraterrestrial life.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Besides revealing that a primary ingredient for life was already in place in the universe between 100 million and 200 million years after the Big Bang, our simulations show that water was likely a key constituent of the first galaxies," the researchers wrote.

Early cosmic uncertainty

One of the biggest issues with the new study is that scientists have never directly observed one of the early stars that the researchers are modeling, known as population III stars. Instead, researchers have only indirectly observed a few of these stellar trailblazers by analyzing the stars that were birthed from their remains, so it's still not certain what they were really like.

If there was abundant water in the early universe, it would also suggest that the cosmos should have accumulated much more water than we currently see in our surroundings.

One explanation for this that has been posited by other scientists is that the universe underwent a drying-out period during which large quantities of water were lost, according to Universe Today. However, it is unclear what the cause of this event could have been.

"There is also the fact that while water formed early, ionization and other astrophysical processes may have broken up many of these molecules," Universe Today reported, meaning that the water from the first supernovas may have been short-lived.

Although water is a key ingredient for life on Earth, there is also no guarantee that its presence in the early universe would have made extraterrestrial life more likely.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Harry is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. He studied Marine Biology at the University of Exeter (Penryn campus) and after graduating started his own blog site "Marine Madness," which he continues to run with other ocean enthusiasts. He is also interested in evolution, climate change, robots, space exploration, environmental conservation and anything that's been fossilized. When not at work he can be found watching sci-fi films, playing old Pokemon games or running (probably slower than he'd like).

-

contrarian While water is certainly a requirement for life, a considerable number of other elements and compounds are also required, not the least are silicates, also formed by reacting with oxygen. These compounds, water and silicates, are likely the two most essential for the appearance of life - water for obvious reasons, and silicates because they are the primary component of planetary formation. Silicates are likely also essential for their unique chemical features at the molecular level in an aqueous environment, features that very likely initiated abiogenesis, and its follow-on life forms.Reply

But many other elements are also required, and most of these are also made by either fusion (carbon, etc.), or by nucleosynthesis. With many stars burning and going out in core collapse supernova in those first few hundred million years noted in the article, you should be getting a lot of everything formed in the early years following the BB.

This all relates to how quickly star systems with stable planets for evolving life could form once their essential components had been formed and dispersed. Certainly it must be longer than 200-300 million years after the BB.

After all, it likely took the proto-Earth at least a hundred million years to form from the 'solar nebula', and probably double that to complete its interaction(s) which formed the moon before stabilizing to its present mass. From these observations alone, it would seem that the first habitable planets would have required far longer than it took for all this water to appear. And this despite the higher mass densities of all these elements and compounds in that time frame.

Anyone aware of any rational studies predicting when the first habitable planets might have formed? Perhaps in the first billion years surely seems probable. -

Unclear Engineer Besides the availability of the necessary chemicals, I wonder what the environments of planets are like when they are in a galaxy that is a quasar. Especially if it is an early "small" galaxy so that most stars are in closer proximity to the quasar emissions. At least life on the surface would probably need :cool:.Reply -

contrarian Reply

This was all the post considered. It was not about habitability, but when the conditions for abiogensis might occur following the BB. Obviously heavy radiation plays a role in the viability of life regardless of circustances, but this is not related to the issue at hand - which is simply the formation of planetary bodies that could give rise to life at some point in their history due to their ideal chemical compositions.Unclear Engineer said:Besides the availability of the necessary chemicals, -

George² Reply

Therefore, after ignoring the other necessary conditions, this article is a completely useless waste of mental energy in the name of the record of when the earliest something could have been. And that's assuming that there was a "big bang" and a beginning.contrarian said:This was all the post considered. It was not about habitability, but when the conditions for abiogensis might occur following the BB. Obviously heavy radiation plays a role in the viability of life regardless of circustances, but this is not related to the issue at hand - which is simply the formation of planetary bodies that could give rise to life at some point in their history due to their ideal chemical compositions. -

Unclear Engineer I don't see much "news" in pointing out that the first massive stars are presumed to have made the elements needed for water. Isn't that the basic theory all along? It seems that "news" would be something to the contrary.Reply

The other part of the "news" is how soon after the "big Bang" those stars are presumed to have developed, run their lives, and gone supernova, releasing those newly created elements into the rest of space, so that planets could form from the "ashes" of the supernovas. But, we really only have theories for what the timelines were for those events, and those theories seem to be challenged at least with respect to timing, every time we start using a bigger telescope.

So, I'll ask, do we think we will ever develop the technology to "see" the population 3 stars and their environments to be able to verify that they were created from nearly pure hydrogen and that there were no other elements in their vicinities during their lifetimes?