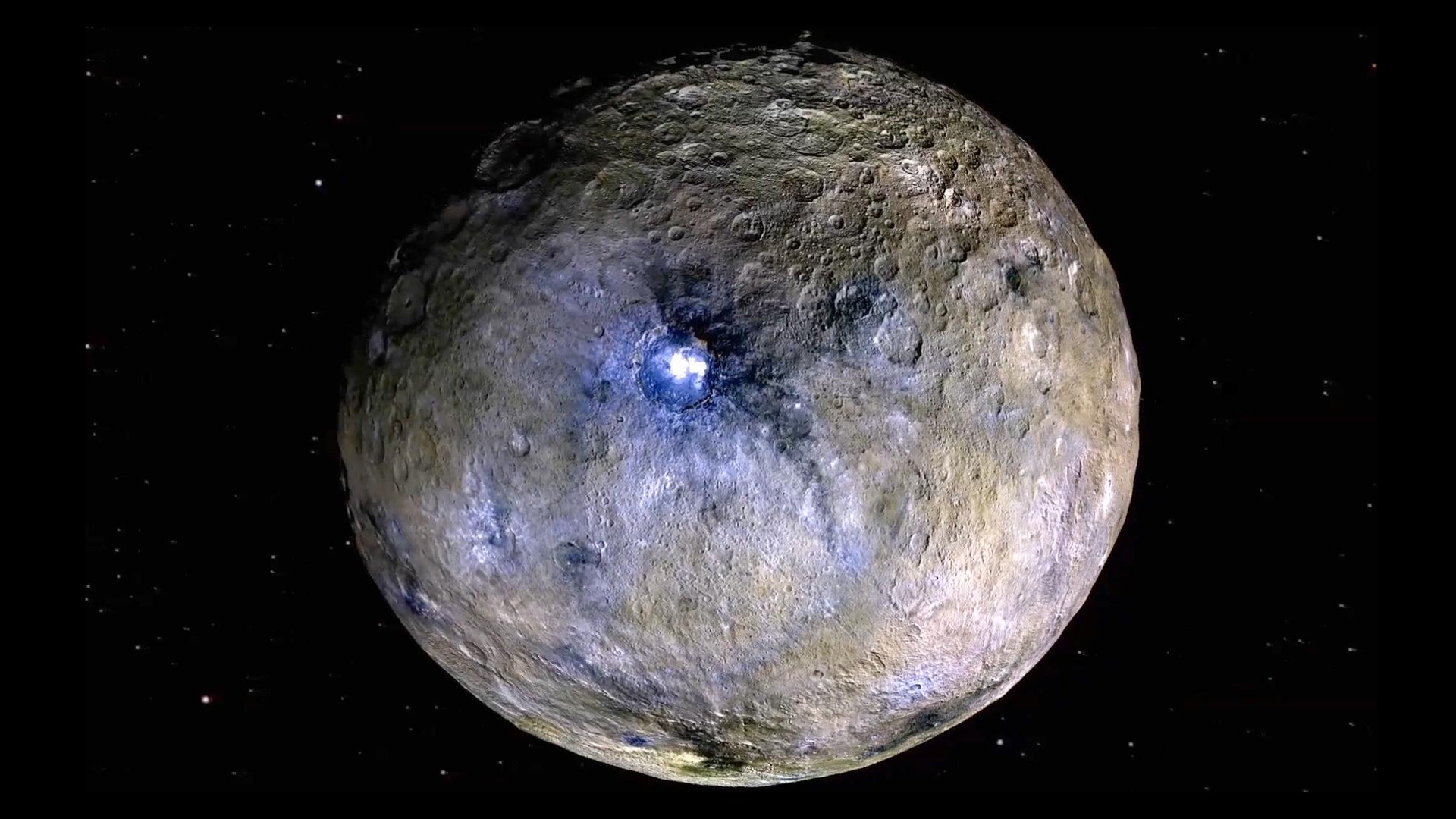

How did life's building blocks end up on dwarf planet Ceres?

The building blocks of life could have been delivered to Ceres by one or more space rocks from the outer asteroid belt.

Using AI to comb through data gathered by NASA's Dawn spacecraft, scientists have conducted a detailed scan of the dwarf planet Ceres to map regions rich in organic molecules to determine whether these "building blocks of life" originated from within the planet or were delivered by external sources.

Ceres boasts a fascinating history. Located in the asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars, it was once classified as an asteroid. However, its size (Ceres makes up 25% of the asteroid belt's total mass) and distinct characteristics set it apart from its rocky neighbors, leading scientists to reclassify it as a dwarf planet in 2006. Ceres is a cryovolcanic world, where ice and other volatile substances are expelled by volcanic activity instead of molten rock.

It is this volcanic activity that led scientists to previously assume that the organic molecules on the dwarf planet were generated and transported from the dwarf planet's interior, but this new AI-powered study suggests a different explanation. "Of course, the first assumption [was] that Ceres' unique cryovolcanism has transported the organic material from the interior of the body to the surface," said Andreas Nathues from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany in a statement. "But our results show otherwise."

Ceres was explored by NASA's Dawn mission, which arrived there in March 2015 and orbited the dwarf planet for about three and a half years. During this time, the spacecraft's scientific camera and onboard spectrometer mapped its entire surface.

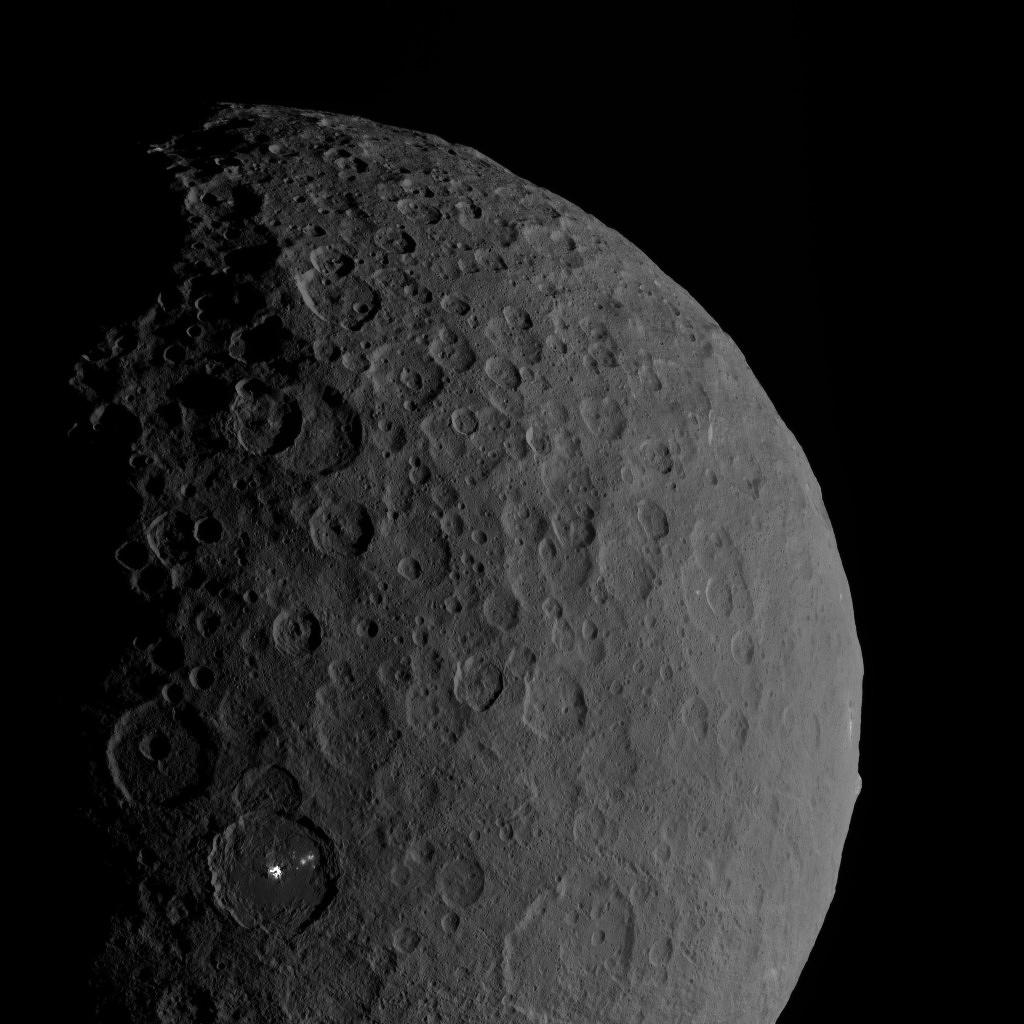

At the time, scientists identified potential patches of organic material by observing that the amount of light reflected from certain areas on Ceres' surface was higher in longer wavelengths. Organic materials, especially those with complex molecules like hydrocarbons, often reflect more light from longer wavelengths due to their molecular structure, which influences how they absorb and scatter light.

Based on their initial analysis, researchers believed that the deposits they identified could contain organic compounds with a chain-like structure, known as aliphatic hydrocarbons. However, their remote data couldn't pinpoint the exact types of molecules with any certainty.

Now, using AI, scientists have reanalyzed the entire surface of the dwarf planet Ceres. While previous studies identified organic compounds in specific regions, AI allowed for a systematic examination of the Dawn mission's full dataset, uncovering patterns that had previously been overlooked.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By cross-referencing spectral data with geological features, AI helped the team confirm that organic materials were in fact not associated with sites of cryovolcanic activity. "Sites of such organic molecules are actually rare on Ceres, and devoid of any cryovolcanic signatures," commented one of the study's scientists, Ranjan Sarkar from MPS, in the statement.

These findings help rule out the possibility that the organic molecules originated from Ceres' interior. Conversely, where organic compounds were reliably detected, there were no signs of deep or surface activity.

"At none of the deposits do we find evidence of current or past volcanic or tectonic activity: no trenches, canyons, volcanic domes or vents. Furthermore, there are no deep impact craters nearby," said Martin Hoffmann, also from MPS.

The vast majority of deposits were located along Ceres' large Ernutet crater in its northern hemisphere. Only three are located at a greater distance from it. Two patches were not previously known.

"Unfortunately, Dawn can't detect all types of organic compounds," said Nathues. "However, the organic deposits that have been reliably detected with Dawn so far likely do not originate [from] Ceres itself."

One plausible explanation researchers propose is that organic material was delivered to Ceres by the impact of one or more asteroids from the outer asteroid belt — a theory supported by computer simulations. These simulations show that such asteroids frequently collide with Ceres, but because they originate from the same general region, their relative velocities are low. As a result, the impacts generate little heat, allowing organic compounds to survive without being destroyed.

This is significant, as it suggests that organic molecules could have been present on asteroids and comets in the outer solar system early in its formation and may have only reached the inner solar system much later, potentially playing a key role in the development of life here on Earth.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.