A red moon: Will the next 'Sputnik Moment' be made in China?

Why being first to return to the moon matters.

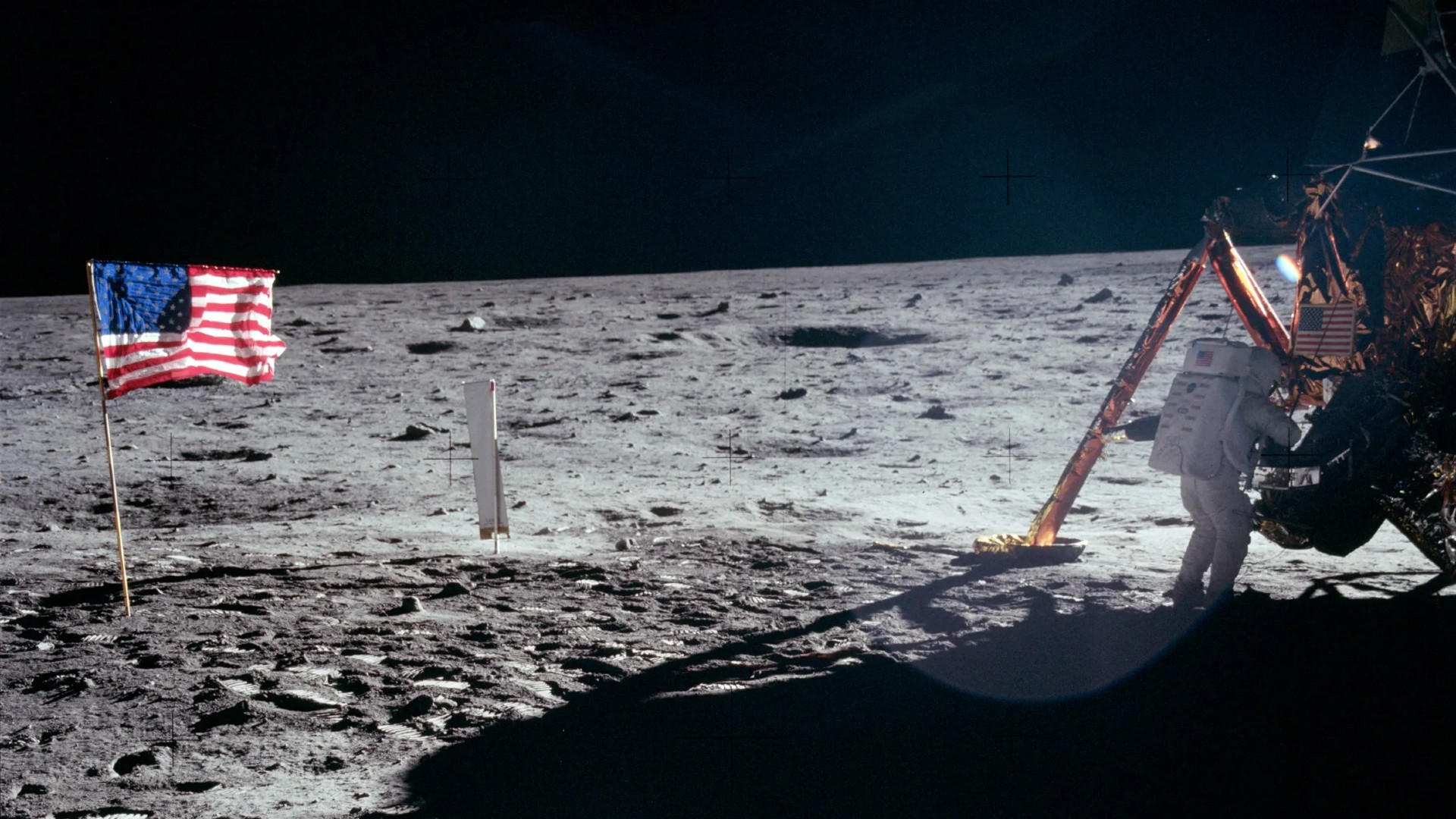

In late 1957, the US Navy's Vanguard rocket was primed to launch the world's first artificial satellite. But, on the morning of Oct. 4, the Soviet Union struck first and lobbed a small metal ball into orbit that Moscow Radio called Sputnik ("Fellow Traveler"). That "Sputnik Moment" had a profound impact on the nascent Space Age, significantly escalating the race between the United States and the Soviet Union, prompting soul searching in the U.S., and spurring a national effort to promote science and math education. America ultimately won the race to the moon, and the benefits changed the nation and the world. The question that confronts us today is: Can the United States prevail again?

Sixty-seven years after Sputnik, space is the great strategic frontier. Yet the U.S. faces growing competition from countries like China and Russia, both of which are targeting Western space assets with economy- and defense-crippling weapons. At the same time, the space economy is exploding as technological advances in reusability, avionics, and artificial intelligence increasingly put lunar resources within reach. Finally, there is geopolitics — the renewed lunar push, initiated under President Trump, is still seen as a geopolitical statement and a symbol of national prestige. The outcome of this lunar competition will have major ramifications today and well into the future.

The next Sputnik Moment will take place — just as it did in the 1950s — against the backdrop of great power competition. This time, the top contenders are the U.S. and China. The winner will not only claim bragging rights but will have first dibs on lunar resources, especially at the moon's south polar region, where safe, sunlit landing sites are scarce. Whoever gets there first will hold the winning hand in setting norms of behavior and rules of governance, which could limit who can access valuable resources for decades to come.

The United States' National Space Policy, released in December 2020, directed NASA to "land the next American man and the first American woman on the moon by 2024, followed by a sustained presence … by 2028." Four years later, both goals remain out of reach. NASA's first crewed lunar landing has slipped repeatedly, with no permanent presence planned for the foreseeable future. In contrast, Beijing has voiced plans to land Chinese "taikonauts" on the lunar surface before 2030 with the prospect of a heavy-lift launch vehicle, crew capsule, and lunar lander flight-ready as early as 2027.

Related: The US is now at risk of losing to China in the race to send people back to the moon’s surface

With so much at stake, Beijing will take great risks to land before the end of 2029, the 80th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC). As usual, China has taken inspiration — and pinched technology — from the United States, emulating the fast-and-expendable Apollo program design of the 1960s. The assistant to the director of the Chinese space agency, Ji Qiming, told China state television, "For now, the development of primary spacecrafts such as the Long March 10 rocket, Mengzhou crew spacecraft, Lanyue lander, and spacesuits are finished." If that's accurate, China leads the U.S. in the race for the next crewed lunar landing.

In contrast, NASA's timeline for the Artemis program is well behind schedule. Artemis 3, the first planned landing mission, had been slated for late 2025 but was recently postponed to no earlier than mid-2027. This date is supported by a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, stating that Artemis 3 is unlikely to land before 2027 due to the pace of lunar lander and spacesuit development. NASA's own internal analysis tagged an early 2028 landing — with an uninspiring 70% confidence level. In other words, there is a 70% chance that NASA's lunar suit and SpaceX's Human Landing System (HLS) will be ready by that date. However, it also means there is a one-in-three chance that critical technology won't be flight-ready till sometime later in 2028 or even 2029.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The China advantage

The contrasting commitment to deadlines is telling. While China single-mindedly pursues a focused and coherent lunar program fortified by a unified political structure, the U.S. lunar program is often swayed by political winds and is struggling to deliver key elements on time. Furthermore, Artemis is architecturally complex and faces regulatory delays. The Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) protracted and byzantine process for issuing Starship launch licenses to SpaceX, critical for Starship lunar lander development, is an example. Though recently improved, the licensing procedures still need streamlining to unleash American industry.

The upshot? The U.S. risks being caught flat-footed once again, as it was in the 1950s. Peter Garretson, co-director of the American Foreign Policy Council's (AFPC) Space Policy Initiative, likens the current situation to the classic fable "The Tortoise and the Hare," with America in the role of overconfident hare. The combination of America's delay and China's steady progress raises the specter that the next humans on the moon will not unfurl the Stars and Stripes. It is entirely possible that the first woman and "person of color" — NASA's stated priority for a first lunar crew — will speak Mandarin, not English. "China and its partners have marched forward, notching one success after another," writes Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's former head of science. "There is no reason to believe they will not be first to send a crewed mission to the lunar south pole."

That prospect should set off alarm bells in Washington. A Chinese crewed landing ahead of the United States would — just as in the original Sputnik Moment — impact the perception of global leadership, thereby reshaping global power dynamics. "You can pretend this won't be a national humiliation," Philip Metzger, cofounder of NASA's Swamp Works, posted on Twitter/X, "but it will … be sold by the CCP as another demonstration of their success and the US's failure, resulting in PRC partnerships and treaties across South America and Africa."

Chinese boots on the moon would surely have wide geopolitical significance, including, critically, broader space governance. Besides reaping geopolitical rewards, China could use the prestige garnered by an early human landing to codify regulations by international bodies that would stymie space development, which the U.S. currently leads.

Related: China plans to build moon base at the lunar south pole by 2035

Maintaining leadership in space

In 2016, President Trump shifted NASA's priority from an improbable crewed flight to a small, captured asteroid to an ambitious mission returning astronauts to the moon — not merely to visit, but to stay and set up a permanent base as a first step toward a crewed landing on Mars. This remarkable public commitment has faced numerous delays and risks getting lost in history.

This is a singular moment in time, sparked by a bold commitment to advance American interests in space. The U.S. should not squander its hard-won technological lead by ceding dominion of cislunar space and the lunar surface to other parties. If we fail to follow through, such a moment may never occur again, and we will have de-facto ceded this new era of spaceflight to China.

Indeed, Beijing's lunar ambitions are more tangible than "flags and footprints." Unlike the United States, the PRC has embraced policies that make economic development a central rationale for spaceflight. The future is not merely a race to be "first" — as important as that is — but rather to exploit space resources and ignite economic growth. The moon itself has more land area than the continent of Africa, but the supply of prime lunar real estate is limited. Landing zones in the coveted south polar regions are strategically important. From these zones, robots and astronauts can access areas of near-constant sunlight for power generation as well as permanently shadowed regions with large reservoirs of valuable resources, including water ice. Lunar ice deposits are critical for making rocket fuel and breathable oxygen to jumpstart the cislunar economy and forge a path to Mars.

Both the United States and China are targeting some of the same sunlit zones, so landing first is critical. "We better watch out … It is not beyond the realm of possibility that they [China] say, 'Keep out, we're here, this is our territory,'" cautions former NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, who served under the Biden Administration. Unfortunately, this lunar contest would take place in a regulatory no man's land with few internationally agreed upon rules and standards of behavior.

Beijing, under the guise of "landing zones," "safety zones," or "research areas," could mount a lunar land grab with economic and geopolitical consequences. Denied access to these resources, NASA and Western enterprises would be squeezed by a lunar standoff as they try to advance their own business plans and resource claims. With moon-related enterprises hanging in the balance, jittery Western investors could turn bearish, fearing that a lunar dispute could undermine business prospects — and possibly spark a confrontation.

Related: Are we prepared for Chinese preeminence on the moon and Mars? (op-ed)

Unleashing American technology and initiative

American launch providers, especially SpaceX, and payload delivery companies, like Intuitive Machines, tower over global competitors … for now. Unleashing the synergy of public and private American space power can achieve extraordinary world-leading results in record time. However, American competitors face headwinds and regulatory hurdles that could trip them up in this lunar competition. The U.S. government needs to balance these private hard chargers with NASA's programs to speed a return to the moon by American astronauts and their international partners.

Elon Musk has declared that each launch of his Starship rocket requires "multiple fish licenses" in addition to lengthy FAA safety reviews. An open letter from his company, SpaceX, called out "patently absurd" regulatory delays. The FAA's snail's pace has also caught the eye of members of Congress, including Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.), a senior authorizer and appropriator who oversees the space sector. These needless delays threaten to hobble Artemis as China paces ahead.

To avoid ceding ground and influence to China and Russia (here and on the moon), the new Trump Administration and Congress should immediately streamline and simplify launch licensing. Elevating the Office of Commercial Space Transportation from the FAA to report directly to the Secretary of Transportation would be a critical first step. "It should be led by a business-savvy professional appointed by and accountable to the president," says professor, author, and space policy expert Greg Autry. Clearing the regulatory and bureaucratic underbrush is the single most impactful and urgent step lawmakers can take to accelerate Artemis.

Currently, the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and crewed Orion capsule are the only available and funded technology to transport astronauts to the lunar neighborhood. However, both are costly and years behind schedule for a crewed launch. Some experts predict SLS will ultimately be replaced because of cost and delays, as reusable superheavy-lift vehicles like Starship and New Glenn come online. Instead of SLS/Orion, the human landing system configuration of SpaceX's Starship or possibly Blue Origin's Blue Moon spacecraft could carry astronauts from Earth to lunar orbit, refuel there, and then land on the lunar surface. There is no reason these human-rated vehicles could not transport crew from the Earth to the moon. Alternatively, a distributed architecture with separate launches of Falcon Heavy and/or New Glenn rockets could boost Orion and an upper stage into low Earth orbit (LEO), where they would dock and perform a translunar injection (TLI) burn. There is room for multiple providers — and the beneficial competition they bring — in this lunar quest.

That is a project for the longer term. For now, the fastest path to the moon is to augment the Artemis program with more power, more energy, and increased speed. As presumptive head of the National Space Council, Vice President J.D. Vance can inject a sense of urgency and energy to get American boots on the ground as soon as possible, and permanently inhabit the moon by 2030, through public-private partnerships. Forward-looking space-economic initiatives, including guaranteed purchase of propellant in orbit, subsidized mining of lunar and asteroid resources, and accelerated timelines, could be game changers. These programs could spur commercial space players to redouble their efforts to develop and monetize cislunar space and the lunar surface. This would spur competition, with SpaceX, Blue Origin, and the traditional aerospace giants vying for contracts at fair, fixed-fee pricing. That's a win for everyone.

Our place in history

Finally, there is the concept of the "Tide of History," or cultural zeitgeist. The original Sputnik Moment triggered an intense and energetic American response, culminating in the triumph of Apollo 11. But some worry about a "reverse Apollo moment." If China returns humans to the moon first, the U.S. could suffer the same global loss of face, the same loss of national pride, and a crippling loss of initiative, which could become an existential crisis for Western democracies as China reshapes the future of spaceflight and human civilization — in space and on Earth.

Resting on past laurels — especially in the new and high-profile frontier of space — is the surest way to lose the future. For a host of reasons — national security, geopolitics, economics, and cultural resonance — being the first to return humans to the moon matters. There is no medal for second place. The world is watching.

John Kross is the Senior Contributing Editor for Ad Astra magazine and a retired medical editor and writer. Rod Pyle is the Editor-in-Chief of Ad Astra magazine and author of "Space 2.0: How Private Spaceflight, a Resurgent NASA, and International Partners are Creating a New Space Age." They contributed this article to contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

John Kross is an author and senior contributing editor of Ad Astra magazine for the National Space Society. Prior to his Ad Astra duties, Dr. Kross was a medical editor/writer and vice president of a medical communications company and publisher. His work has appeared in medical journals, professional conferences, as well as space-focused publications such as Sky and Telescope and 21st Century Science. Personal highlights of his career include coauthoring an article with Apollo 11 astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and contributing to the space reference book, Space Sciences. He is the author of “America’s Path to Deep Space.”