Bullet-fast moon rocks carved 2 lunar gorges deeper than the Grand Canyon

It only took less than 10 minutes.

Two gigantic canyons on the moon — both deeper than the Grand Canyon — were carved in less than 10 minutes by floods of rocks traveling as fast as bullets, a new study finds.

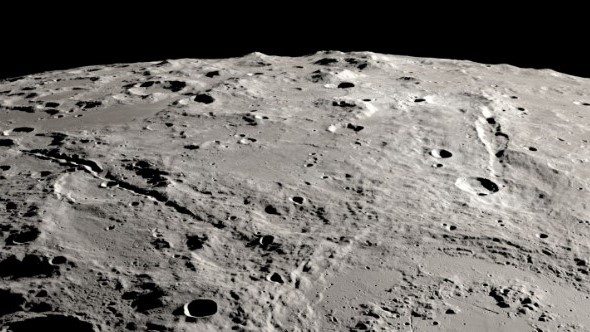

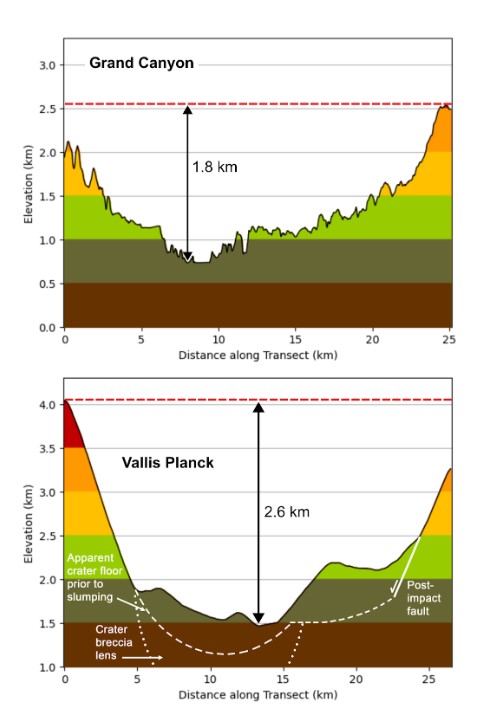

Scientists analyzed the lunar canyons, named Vallis Schrödinger and Vallis Planck, to find that these huge valleys measure 167 miles long (270 kilometers) and nearly 1.7 miles (2.7 km) deep, and 174 miles long (280 km) and nearly 2.2 miles deep (3.5 km), respectively. In comparison, the Grand Canyon is 277 miles long (446 km) and is, at most, about 1.2 miles deep (1.9 km), the researchers noted.

"The lunar landscape is dramatic," David Kring, a geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute of the Universities Space Research Association, told Space.com. "In the lunar south polar region, there are mountains that exceed Mt. Everest in height and canyons that exceed the Grand Canyon in depth. Future lunar surface explorers will be awed."

This pair of lunar canyons represents two of many valleys radiating out from Schrödinger basin, a crater about 200 miles wide (320 km) that was blasted out of the lunar crust by a cosmic impact about 3.81 billion years ago. This structure is located in the outer margin of the moon's largest and oldest remaining impact crater, the South Pole–Aitken basin, which measures about 1,490 miles wide (2,400 km) and dates about 4.2 billion to 4.3 billion years old.

Kring and his colleagues investigated the Schrödinger basin for potential landing sites for future robotic and human lunar missions. They analyzed photos from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to better understand how Vallis Schrödinger and Vallis Planck formed, generating maps from these images of the moon's surface to calculate the direction and speed of debris expelled from the collision that created Schrödinger basin.

The scientists estimate that rocky debris flew out from the impact at speeds between 2,125 to 2,860 miles per hour (3,420 to 4,600 km/h). In comparison, a bullet from a 9mm Luger handgun might fly at speeds of about 1,360 mph (2,200 km/h).

The researchers suggest the energy needed to create both of these canyons would have been more than 130 times the energy in the current global inventory of nuclear weapons.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The lunar canyons we describe are produced by streams of rock, whereas the Grand Canyon was produced by a river of water," Kring said. "The streams of rock were far more energetic than the river of water, which is why the lunar canyons were produced in minutes and the Grand Canyon produced over millions of years."

The angle at which the collision occurred led the resulting debris to scatter in an uneven manner around the Schrödinger basin, with less material covering the area closer to the South Pole–Aitken basin. With less debris covering this ancient region, astronauts that land there "will find it easier to collect samples from the earliest epoch of the moon," Kring said.

The scientists detailed their findings in a paper published on Feb. 4 in the journal Nature Communications.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us

-

m4n8tpr8b Interesting article, and the paper it is based on is even more interesting.Reply

Craters have the paradox that they are almost round regardless of the impact angle (well within bounds, the shallowest impact angles do produce oval craters). The basic level explanation has to do with the conservation of momentum an energy: most of the kinetic energy of the impacting object is turned into heat and a shock wave travelling through the impacted body outwards, turning into the kinetic energy of the ejecta (which has orders of magnitude higher mass than the impacting object), much of the moment is carried by a small portion of the ejecta that also has the highest velocity. But more detailed simulations (cited in the paper) show this is a simplification: at shallower impact angles, the original impact point will be at the uprange edge of the eventual crater, and the ejecta will leave in a butterfly pattern, with the fastest ejecta focused along certain directions, and the exact pattern depends on many factors (impact angle and speed, impactor size, surface gravity of the impacted object.)

Even the paper doesn't say so but the ejecta-produced canyons of the Schrödinger Basin still don't resemble any of the simulated patterns from earlier studies, in particular their angle. It's worth more research. -

Unclear Engineer A couple of thoughts:Reply

First, the velocities stated in the article don't seem particularly high, to me. The muzzle velocity of a typical military rifle round is about 2,200 mph, and the fastest rifle cartridge muzzle velocity is about 2,700 mph. Escape velocity from the Moon is only about 5,100 mph.

A single "bullet" that shot straight through 170 miles of rock would be impossible, though. But that is not what the subject paper is saying happened. The hypothesis of the paper is that streams of rocks were ejected from the impact point along 2 rather narrow directions, and those rocks came down in the two straight lines to make strings of secondary craters. Although that does seem much more plausible than a single, very low angle projectile being able to penetrate so far sideways, the pictures of the resulting canyons look more "plowed through" than a bunch of circles strung closely together. So, I am trying to envision a stream of rocks flying at low angles such that the near ones hit and make craters that are quickly extended on their far sides as additional rocks hit their rims and make additional craters farther from the initial impact site. And so on, for 170 miles in a straight line. Actually 2 straight lines.

That sort of makes sense to me But the narrowness of those 2 streams of rocks diverging from each other by a substantial horizontal angle makes me wonder it those rocks were more related to the original impactor breaking/exploding into 2 pieces, rather than some sort of inhomogeneity in the impacted surface that could have directed the surface ejecta into such tight patterns in 2 directions, as well as making the other observed spread pattern of ejecta.

Even when (if) astronauts get there to take a close look, it is probably going to be long time before humans get to travel distances like 200 miles across broken lunar terrains. So, info may be slow coming. -

whoknows Are there antipodal maps for the Moon with meaningful data?Reply

Mars might have linked "opposites"

eg :-

"The shield volcano Alba Mons however is almost exactly antipodal to the Hellas Basin."

https://astronomy.stackexchange.com/questions/34749/are-tharsis-montes-and-hellas-basin-a-result-of-the-same-event.

Interpret that how you will, but it would be interesting to see if there are antipodal formations corresponding with the Schrödinger and Aitken basins? (and separately the Moon's mares) -

m4n8tpr8b ReplyUnclear Engineer said:But the narrowness of those 2 streams of rocks diverging from each other by a substantial horizontal angle makes me wonder it those rocks were more related to the original impactor breaking/exploding into 2 pieces, rather than some sort of inhomogeneity in the impacted surface that could have directed the surface ejecta into such tight patterns in 2 directions, as well as making the other observed spread pattern of ejecta.

whoknows said:Are there antipodal maps for the Moon with meaningful data?

Mars might have linked "opposites"

eg :-

"The shield volcano Alba Mons however is almost exactly antipodal to the Hellas Basin."

https://astronomy.stackexchange.com/questions/34749/are-tharsis-montes-and-hellas-basin-a-result-of-the-same-event.

Interpret that how you will, but it would be interesting to see if there are antipodal formations corresponding with the Schrödinger and Aitken basins? (and separately the Moon's mares)

Unclear Engineer said:That sort of makes sense to me But the narrowness of those 2 streams of rocks diverging from each other by a substantial horizontal angle makes me wonder it those rocks were more related to the original impactor breaking/exploding into 2 pieces, rather than some sort of inhomogeneity in the impacted surface that could have directed the surface ejecta into such tight patterns in 2 directions, as well as making the other observed spread pattern of ejecta.

There was no breaking into pieces, and inhomogeneity of the impacted surface also can only have little influence. This was an impact by an object dozens of kilometres across. Even a hundred-metre object would completely melt upon impact, along with a lot of mass of the impacted surface, and the ejecta pattern is produced by shock wave and fluid dynamics. Those two canyons weren't all the ejecta (you can see the ejecta blanket map in the paper), it was just the highest-velocity part of the ejecta.

If you check another paper, cited as source 44 in this paper, you can see several nice diagrams showing the pattern and evolution of ejecta blankets at different impact parameters. At shallower angles, two streams of high-velocity ejecta seem quite common, albeit in those simulations, the angles differ from those for the Schrödinger Basin, so some other factor modified the pattern.

I don't think astronauts are of much use for observations of these canyons.Unclear Engineer said:Even when (if) astronauts get there to take a close look, it is probably going to be long time before humans get to travel distances like 200 miles across broken lunar terrains. So, info may be slow coming. -

Unclear Engineer I have not read deeper than the cited paper, so don't know details in the paper's references.Reply

So, I am wondering about the posted statement that the impacting material would be "completely melt upon impact".

How does a rubble pile asteroid melt immediately in a homogeneous manner? Or a comet?

Especially if there were substantial amounts of more volatile constituents with less volatile clumps, I can visualize all sorts of non-uniform dispersal patterns. And, with an impactor estimated at dozens of kilometers across, impacting directly at a shallow angle, without interactions with an atmosphere, it seems most likely to me that the first effects would occur on the lower edge and propagate upward through the impactor, perhaps spreading and even somewhat lofting the upper fragments before they reach the surface of the Moon farther along the impactor's initial trajectory.

Actually, it is hard for me to accept a model that simply assumes the impactor instantaneously and uniformly transforms from solid to a liquids before any dispersal. Is that what the paper assumes in its simulations? -

m4n8tpr8b Reply

On Mercury, the Caloris Basin has an antipodal chaos region. Given that the Moon is smaller while the South Pole-Aitken basin is larger, there certainly was an antipodal chaos region. However, don't look for it, because the crater formed when the Moon was very young and several massive impacts followed, blanketing older features in their own ejecta and eroding them with moonquakes.whoknows said:Interpret that how you will, but it would be interesting to see if there are antipodal formations corresponding with the Schrödinger and Aitken basins? (and separately the Moon's mares)

For the Schrödinger Basin, go here, change Projection to "Lunar Globe (3D)", and type "-75,132.4" into the search field. (You'll see the whole crater from about a height of 500 km.) You'll find the antipodal region by typing in the antipodal coordinates, which are "75,312.4". It's not particularly noteworthy because it is a bunch of old craters filled with younger lava just like neighbouring areas, thus even if there was a chaos regio, it is mostly covered in the lava. -

m4n8tpr8b Reply

By the time it hits a solid body, it doesn't matter what the impactor is composed of - it can be solid iron or it can be a dense cloud of dust, if it has the same mass, and reaches the bottom of the atmosphere at the same speed, the end result is basically the same. Consider the amount of kinetic energy that has to be absorbed and the time in which it has to be absorbed. Asteroids travel at speeds in the range of dozens of kilometres per second. They cannot sustain any structural integrity and will completely melt upon impact in about the time it takes for the asteroid to travel a distance equivalent to its diameter. Even for an impactor as large as necessary to form the Schrödinger Basin, this is just a second or two. It will take several more seconds for the shock wave to travel outwards and excavate the initial crater (which is roughly ten times wider than the impactor, with a volume hundreds of times larger), during which time a lot of impacted material also experiences enough extreme pressure & shear & heat to also melt.Unclear Engineer said:I have not read deeper than the cited paper, so don't know details in the paper's references.

So, I am wondering about the posted statement that the impacting material would be "completely melt upon impact".

How does a rubble pile asteroid melt immediately in a homogeneous manner? Or a comet?

In fact, in vacuum, even fist-sized impactors are enough to produce a plasma "fireball", which is visible by telescopes on Earth as flashes of light. That's how impacts on the Moon have been observed in recent years.

Actually, it is hard for me to accept a model that simply assumes the impactor instantaneously and uniformly transforms from solid to a liquids before any dispersal. Is that what the paper assumes in its simulations?

I didn't say "instantaneous", nor did I say that it is an "assumption". Such simulations are complex 3D simulations that consider all the relevant laws of physics and material properties of both impactor & impacted ground. The melting - in fact, to a good part, vaporization - of material can be seen as a result of the simulations. -

Unclear Engineer Still, in the end, the results visible on the Moon and in the simulations that try to mimic it are not uniformly distributed. There are those 2 canyons going out in straight lines, plus a more common splash/spray pattern of similar extent. So, there are clearly some dynamic processes that are more complex than impactor-hits-surface-and-melts going on.Reply

I even wonder if "upper" parts of the impactor retained sufficient velocity to escape the Moon's gravity and not impact anywhere. With the moons escape velocity at only 2.4 km/s, it seems like something moving at "dozens of kilometers per second" and striking at a shallow angle would be a good bet for partially escaping back into space. Probably shedding slower moving material under it along its path. Or, paths, if it broke apart during the impact.

While 3D simulations are modeled based on laws of physics, they necessarily contain assumptions about various important parameters, even at the individual finite element level. When those are not known for sure, a variety of possibilities is usually tried.

Modeling is not "truth", but rather an attempt to understand how something observed could have come to exist/occur. There is a tendency for modelers to think they have the right answer when they can at least roughly produce the observed effect with a simulation. But, that has substantial vulnerability to confirmation bias. There are plenty of examples in science of theories that seemed to be supported by evidence being overturned by further analysis showing the same results due to different phenomena.

So, it would be interesting to know how detailed the 3D simulations were with respect to the dynamics of the impactor morphology changes. How do the kinetic energies and momenta of the upper parts of the impactor get changed? By impacting the surface themselves, or by effects from lower impactor parts having already impacted the surface?

And, with the high fraction of orbiting pairs of asteroids, even of pairs stuck together, along with the tidal disruptive forces of encounters with massive bodies like the Moon (and nearby Earth), how are we even sure that there was only one impactor part to begin with? -

m4n8tpr8b Reply

I never said anything about uniform distribution, in fact, quite the opposite.Unclear Engineer said:Still, in the end, the results visible on the Moon and in the simulations that try to mimic it are not uniformly distributed.

So, there are clearly some dynamic processes that are more complex than impactor-hits-surface-and-melts going on.

I never said there weren't. I only countered your idea that the pattern could have been produced by surface features or the impactor breaking apart, which severely underestimates the impact energy and its effects on the impactor & impacted terrain. That is: the impact does much more than break the impactor into pieces.

Unclear Engineer said:I even wonder if "upper" parts of the impactor retained sufficient velocity to escape the Moon's gravity and not impact anywhere.

Parts of the impactor: unlikely, again because of the melting/evaporation, and also the direction change. However, you're not that far off, because parts of the blasted-out impacted ground can very well reach escape velocity. In fact, that's how meteors from the Moon and Mars could get to Earth, and we even have identified some small near-Earth asteroids that had to be ejecta from the Moon due to their very Moon-like surface composition (read up on Earth's quasi-satellite Kamo'oalewa, for which we could even identify the crater it came from, and it wasn't even that big of a crater).

Modelers are much more aware of this than you are :) You should really read the paper I suggested.Unclear Engineer said:Modeling is not "truth", but rather an attempt to understand how something observed could have come to exist/occur.

That depends on multiple factors, above all the impact angle.Unclear Engineer said:How do the kinetic energies and momenta of the upper parts of the impactor get changed? By impacting the surface themselves, or by effects from lower impactor parts having already impacted the surface?

Right upon first contact, several processes start at the same moment: evaporation of both impacting and impacted material and its expansion due to tremendous pressure, shock waves travelling through both at the speeds typical for solid materials (much higher than the speed of sound in air but still much slower than the asteroid's impact speed) and breaking them apart at a microscopic level, elastic compression of the impacted ground (in the case of such a big impact, on the scale of kilometres!) that will eventually lead to a rebound (this is what produces central peaks or rings in larger craters; including the prominent ring still visible in spite of lava fill-up in the Schrödinger Basin); the mixing together of impactor and impacted material; and more. We are talking about the big picture but it is actually a rather complex process.

During the course of the impact, the original material of the impactor will first deform greatly. Exactly how depending on the angle of impact: in a steeper impact, the entire asteroid material gets squished lie a dropped fruit, but in a shallow impact, it might get elongated and the lower to upper parts can progressively impact the ground.

However, progressively, you cannot talk about the original impactor material separately as it will mix with the impacted material, and in fact a good part of this mix will rise above the forming crater in a giant fireball (the one key element of big impacts almost never shown in films & TV shows). Do you know about the iridium that was found in the rock layer separating the Cretaceous and Paleogene (formerly Tertiary) layers around the world and was the first evidence for the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs? That iridium is not in the form of nuggets or dust, it is trace amounts found everywhere in what used to be material similar to ash. It is actual material from the impactor that condensed out of that fireball and got everywhere around Earth through the atmosphere, "contaminating" the fallen-back ejecta and the dust clouds in the atmosphere that caused the decade-long 'nuclear winter'.

That's actually half a good point: a contact binary might produce more weird eject patterns. (I recall reading that there were already simulations of such impacts but the one study referenced above did not cover it.) Binary asteroids with larger separation would produce not only more weird ejecta patterns but also non-circular craters, though.Unclear Engineer said:And, with the high fraction of orbiting pairs of asteroids, even of pairs stuck together, along with the tidal disruptive forces of encounters with massive bodies like the Moon (and nearby Earth), how are we even sure that there was only one impactor part to begin with? -

m4n8tpr8b This is as good a place as any to talk about how giant impacts in fiction cannot fully show how extreme conditions are.Reply

In Armageddon, a giant asteroid is split into two halves that recede enough in a day to both fly past Earth. Given that gravity between the two halves will slow the separation, how big Earth is, and how its gravity will change the orbit of the two halves, the separating blast would need to give the halves an initial speed in the order of hundreds of metres per second. The adteroid being the size of Texas, even if it had just the density of water, the separating blast would need to be in the order of dozens of billions of megatons. And, of course, even if the asteroid would be a contact binary rather than the weird non-compact but single-body ice dwarf in the movie, you would get a lot of large splinters in the middle in addition to the two big halves, and those would be enough to wipe us out.

In Deep Impact, minutes before impact, the impactor is blown into tiny pieces that harmelssly burn up in the atmosphere. But those tinly pieces would carry the same kinetic energy. Even if the first few hundred pebbles in each square metre burn up, they would clear the way for millions more behind them, and you would still get a crater the same size. Things would be better if the blowing into tiny pieces happened not minutes but days before impact and the cloud of pebbles could expand to say 1,000 km across. But they would still carry all the kinetic energy and deposit that into the atmosphere, along with high-altitude dust, causing severe climatic distruption at the least.

Also in Deep Impact but also in several other films/shows, you have people looking up in the sky in horror as an approaching asteroid starts to burn in the upper atmosphere before impact. In reality, the asteroid would be brighter than the Sun, blinding eyewitnesses and giving them severe burns. (Even the Chelyabinsk meteor caused milder injuries of these kinds).

One thing almost never shown on screen (the only I can recall is in the TV show The Expanse) is that immediately after impact, a giant fireball will rise above the forming crater. This again will be much brighter than the Sun (for several seconds for a large impact), in fact, much worse than before impact: its radiation heat is enough to set anything alive with direct line of sight on fire. (For the Chixculub impact, the affected area extended as far as Florida.) This is the most immediate effect of the impact, arriving before the earthquakes, the airblast, the falling-back ejecta and the secondary fires it starts, and the tsunami (more or less in that order).

In Greenland, people hide from an impact in bunkers. But the earthquake would shatter those bunkers and shake everything inside apart even if not, no way life support systems would keep functioning.