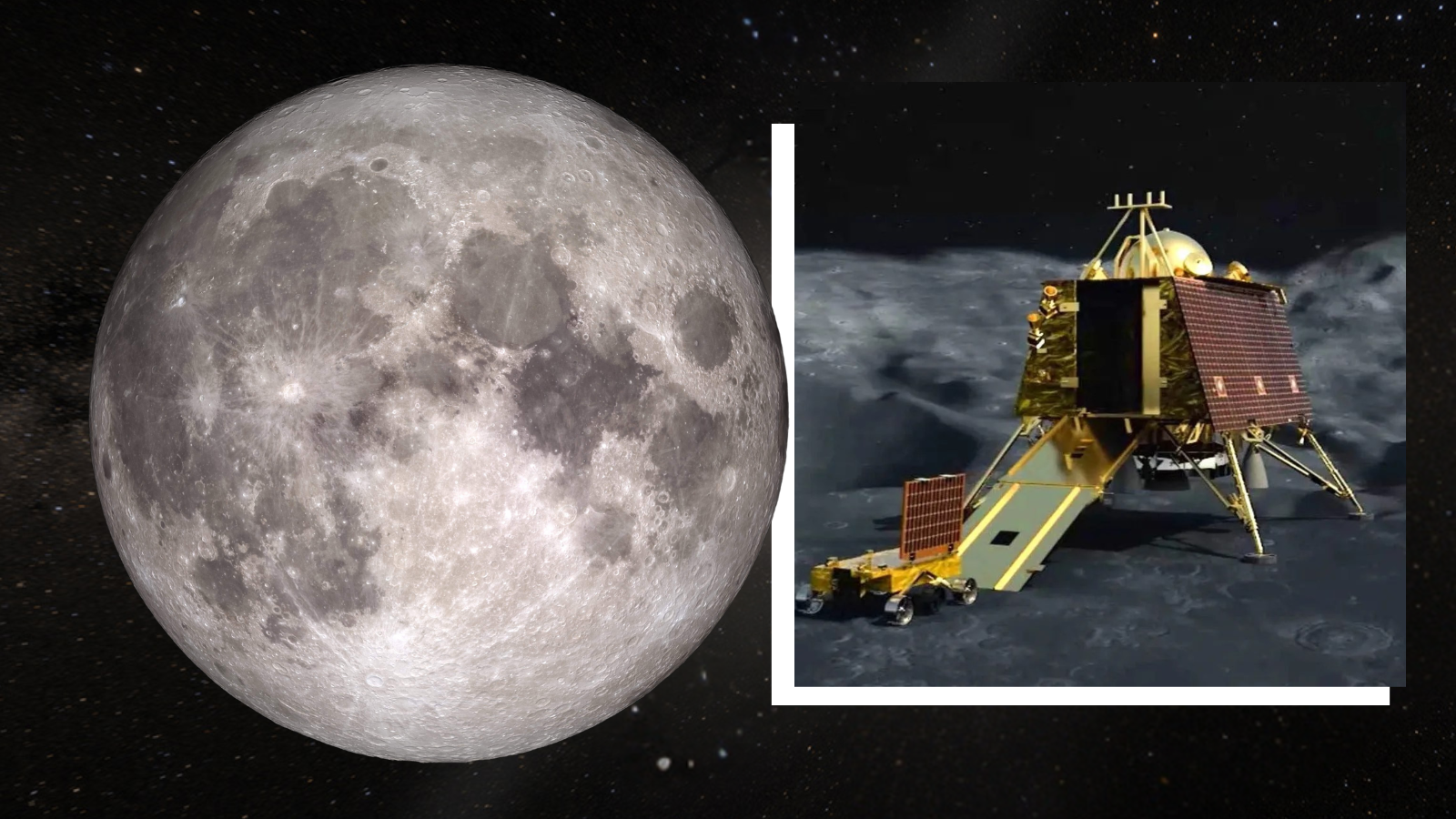

Water mining on the moon may be easier than expected, India's Chandrayaan-3 lander finds

Higher latitudes on the moon with slopes facing the poles "are not only scientifically interesting but also pose less technical challenges for exploration in comparison with regions closer to the poles of the moon."

Future astronauts traveling to the moon may have easier access to life-sustaining water and extractable ice than previously thought, according to new research.

A team of scientists led by Durga Prasad of the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad analyzed lunar temperature data collected on site by India's Chandrayaan-3 mission, which landed near the moon's south pole in August 2023. The researchers found that temperatures at the spacecraft's landing site fluctuated dramatically, even among areas that are very close to each other.

To better understand these temperature swings, the researchers plugged this data into a computer model they fine-tuned to match the spacecraft's landing conditions, including local topography and illumination. The results suggest higher latitudes on the moon with slopes that face its poles share conditions similar to those at Chandrayaan-3's landing site. These regions typically receive less intense solar energy, which leads to cooler surface temperatures that could allow for the accumulation of ice at relatively shallow depths. This means such lunar areas would present fewer technical challenges for accessing local resources compared to the more extreme conditions at the moon's crater-riddled poles, the researchers say.

The findings hold significance for agencies planning long-term crewed missions to the moon's south pole, such as NASA with its Artemis program. If ice can be found and harnessed on the moon, it could reduce astronauts' reliance on Earth-based supplies, making missions more sustainable and cost-effective. Water extracted from ice could serve multiple purposes for astronauts, not only as drinking water but also for producing rocket fuel by splitting water molecules into their constituent parts — oxygen and hydrogen.

For decades, however, the only direct measurements of the moon's surface temperature were taken during the Apollo 15 and 17 missions in the 1970s, both of which landed near the moon's equator — far from the proposed sites for future polar missions.

In August 2023, shortly after the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft notched a flawless touchdown near the lunar south pole, an instrument onboard its lander, called ChaSTE — short for Chandra's Surface Thermophysical Experiment — bored into the moon's soil, reaching a depth of up to 10 centimeters (4 inches) and measured local temperatures over the course of a lunar day.

The recorded data showed temperatures at the spacecraft's landing site that's on a sunward-facing slope — named "Statio Shiv Shakti" — peaked at 179.6 degrees Fahrenheit (82 degrees Celsius) and plummeted to -270.67 degrees F (-168.15 degrees C) during the night. However, just a meter away, where the terrain flattened out and faced toward the pole, the temperature peaks were much lower, reaching just 138.2 degrees F (59 degrees C).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Simulations suggest that slopes greater than 14 degrees in higher latitudes, but facing in the poleward direction, may be cool enough for ice to accumulate at shallow depths. And these conditions are similar to those proposed for future lunar south pole landing missions, including with NASA's Artemis moon missions, the researchers write in their new study:

"Such sites are not only scientifically interesting but also pose less technical challenges for exploration in comparison with regions closer to the poles of the moon."

The study was published on Thursday (March 6) in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social