Oxygen discovered in most distant galaxy ever seen: 'It is like finding an adolescent where you would only expect babies'

"I was astonished by the unexpected results because they opened a new view on the first phases of galaxy evolution."

Astronomers have found oxygen in the farthest, and thus the earliest, galaxy ever seen. This marks the most distant detection of oxygen ever made by humanity.

This early galaxy, designated JADES-GS-z14-0, has 10 times the amount of heavy elements that would be expected in a galaxy that existed just 300 million years after the Big Bang. The findings indicate that this galaxy was already mature in the early universe, challenging theories of galactic evolution.

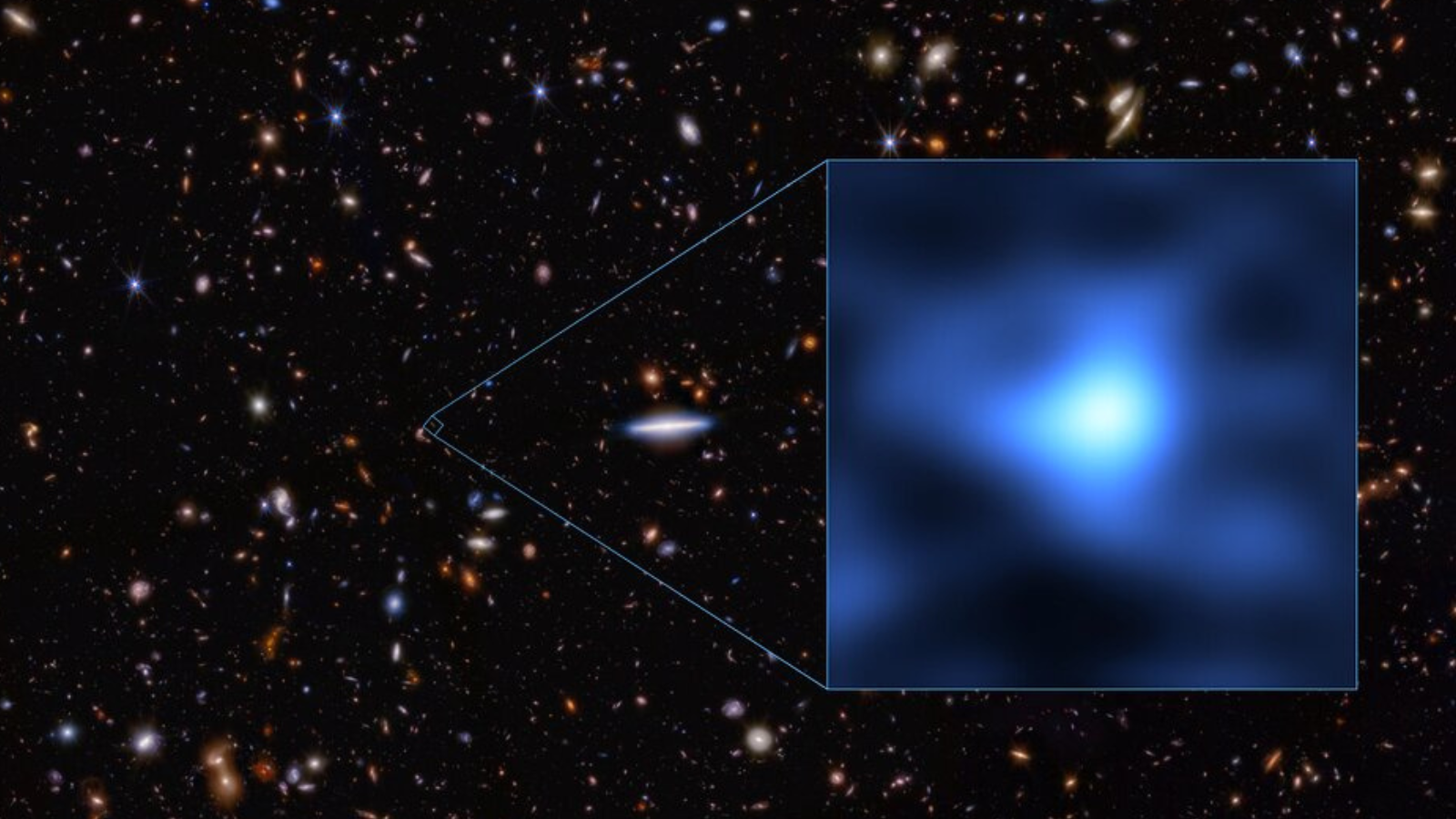

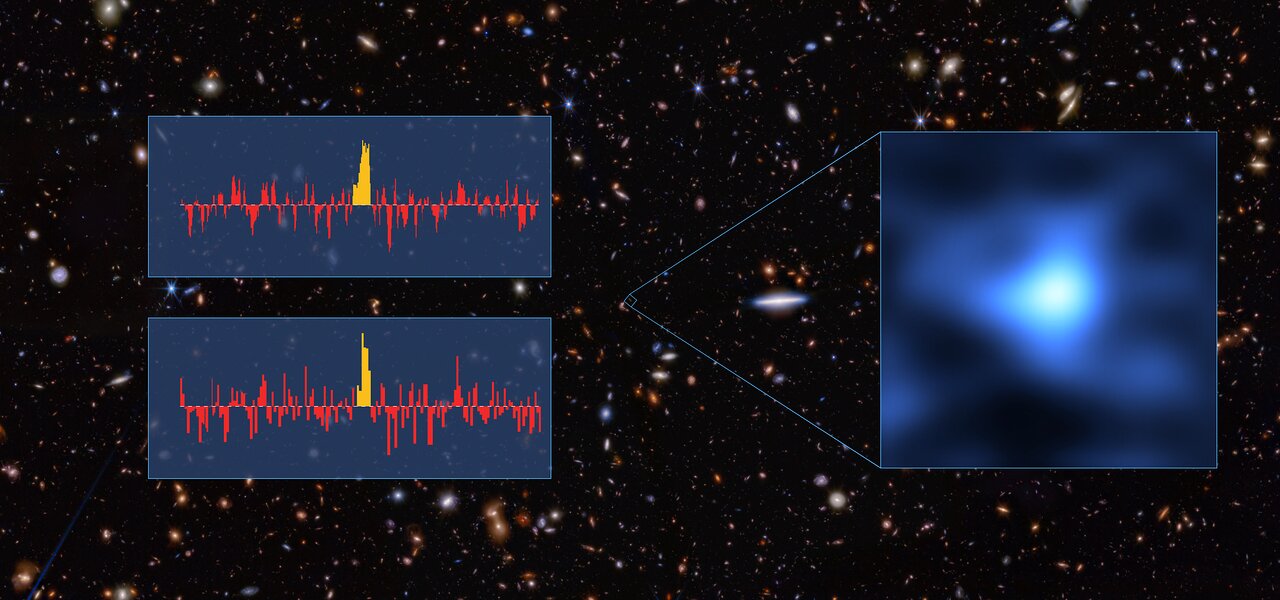

JADES-GS-z14-0 was discovered in 2024 by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST); its light had taken about 13.4 billion years to travel to us, equivalent to around 98% of the 13.8 billion-year-old universe's lifetime. The newly unearthed chemical composition of JADES-GS-z14-0 came courtesy of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

"It is like finding an adolescent where you would only expect babies," team member and Leiden Observatory researcher Sander Schouws said in a statement. "The results show the galaxy has formed very rapidly and is also maturing rapidly, adding to a growing body of evidence that the formation of galaxies happens much faster than was expected."

JADES-GS-z14-0 was spotted alongside several other similarly early galaxies as part of the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) program. This project aims to provide vital insights into how stars, gas and black holes evolved within primordial galaxies when the 13.8 billion-year-old universe was very young.

Why is JADES-GS-z14-0 so metal?

To understand why it is so surprising for heavy elements to be discovered in an early galaxy like JADES-GS-z14-0, it is necessary to consider the chemical composition of the infant universe.

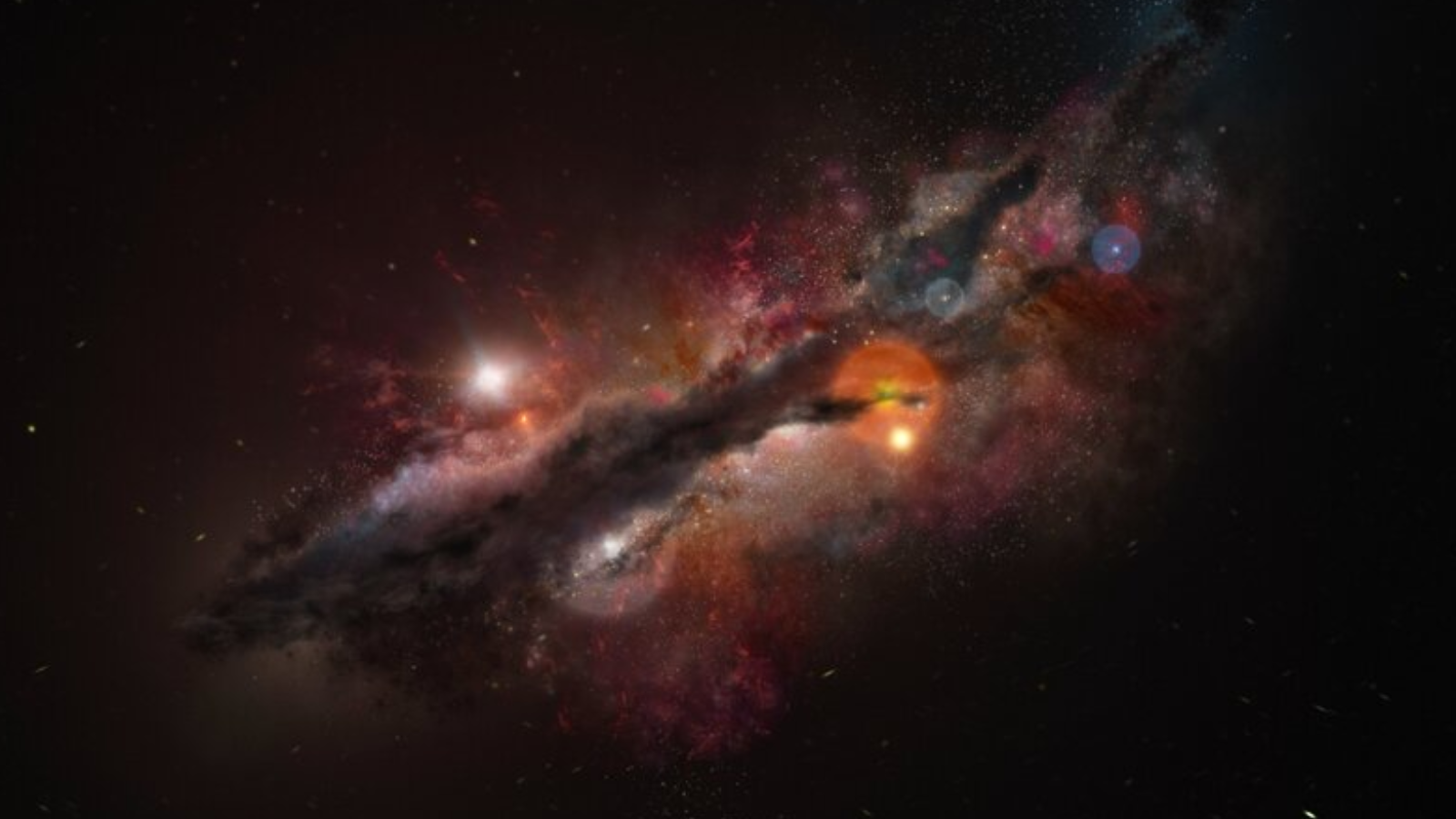

When the universe was 2% of its current age, scientists think it was filled predominantly with hydrogen, the lightest element in the cosmos, some helium, and a tiny smattering of heavier elements, which astronomers somewhat confusingly call "metals." This means stars and galaxies seen during this period should be correspondingly "metal-poor."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As these first stars died and exploded in supernova explosions, the metals they had forged during their lives were dispersed, enriching the gas clouds within their home galaxies. These clouds eventually formed the next generation of stars, which were therefore more metal-rich.

That means the older a galaxy gets, the more its "maturity" can be measured based on the abundance of metals it holds. And, seen at 300 million years into the life of the cosmos, JADES-GS-z14-0 should be metal-poor and "immature" — yet it appears to be mature.

“I was astonished by the unexpected results because they opened a new view on the first phases of galaxy evolution," team member Stefano Carniani of the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa, Italy, said in the statement. "The evidence that a galaxy is already mature in the infant universe raises questions about when and how galaxies formed."

The detection of oxygen in this early galaxy has also allowed astronomers to measure the distance to JADES-GS-z14-0 more precisely.

"The ALMA detection offers an extraordinarily precise measurement of the galaxy’s distance down to an uncertainty of just 0.005%," team member Eleonora Parlanti of the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa, Italy, said. "This level of precision — analogous to being accurate within 5 cm over a distance of 0.62 miles [1 kilometer] — helps refine our understanding of distant galaxy properties."

While it took the JWST to discover this incredibly distant galaxy, the precise measurement of its distance from Earth wouldn't have been possible without ALMA.

"This shows the amazing synergy between ALMA and JWST to reveal the formation and evolution of the first galaxies," team member and Leiden Observatory astronomer Rychard Bouwens said in the statement

Gergö Popping is an astronomer at the European ALMA Regional Center who was not involved in this research.

"I was really surprised by this clear detection of oxygen in JADES-GS-z14-0," he said. "It suggests galaxies can form more rapidly after the Big Bang than had previously been thought.

"This result showcases the important role ALMA plays in unraveling the conditions under which the first galaxies in our universe formed."

The team's research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.