Scientists are starting to take the measure of the monster volcanic eruption that rocked the South Pacific kingdom of Tonga earlier this month.

The undersea volcano had been burbling since late December 2021, shaking the seas near Tonga with a series of outbursts. Things kicked into higher gear this month, with powerful blasts on Jan. 13 and Jan. 14 and then an even bigger eruption on Jan. 15 that sent ash and dust 25 miles (40 kilometers) into the Pacific sky.

Satellite photos showed the most recent eruption to be titanic, and researchers are now putting some numbers on it.

Related: 10 incredible volcanoes in our solar system

"This is a preliminary estimate, but we think the amount of energy released by the eruption was equivalent to somewhere between 4 to 18 megatons of TNT," Jim Garvin, chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement.

"That number is based on how much was removed, how resistant the rock was and how high the eruption cloud was blown into the atmosphere at a range of velocities," Garvin added.

For perspective: The 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens in Washington released about 24 megatons of TNT equivalent, and the famous 1883 explosion of Indonesia's Krakatau is estimated to have unleashed 200 megatons or so, NASA officials said in the same statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The atomic bomb that the United States dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in July 1945 released the energy of roughly 15 kilotons of TNT. There are 1,000 kilotons in a megaton, so the high end of the Tonga volcano estimate is equivalent to about 1,200 Hiroshima bombs.

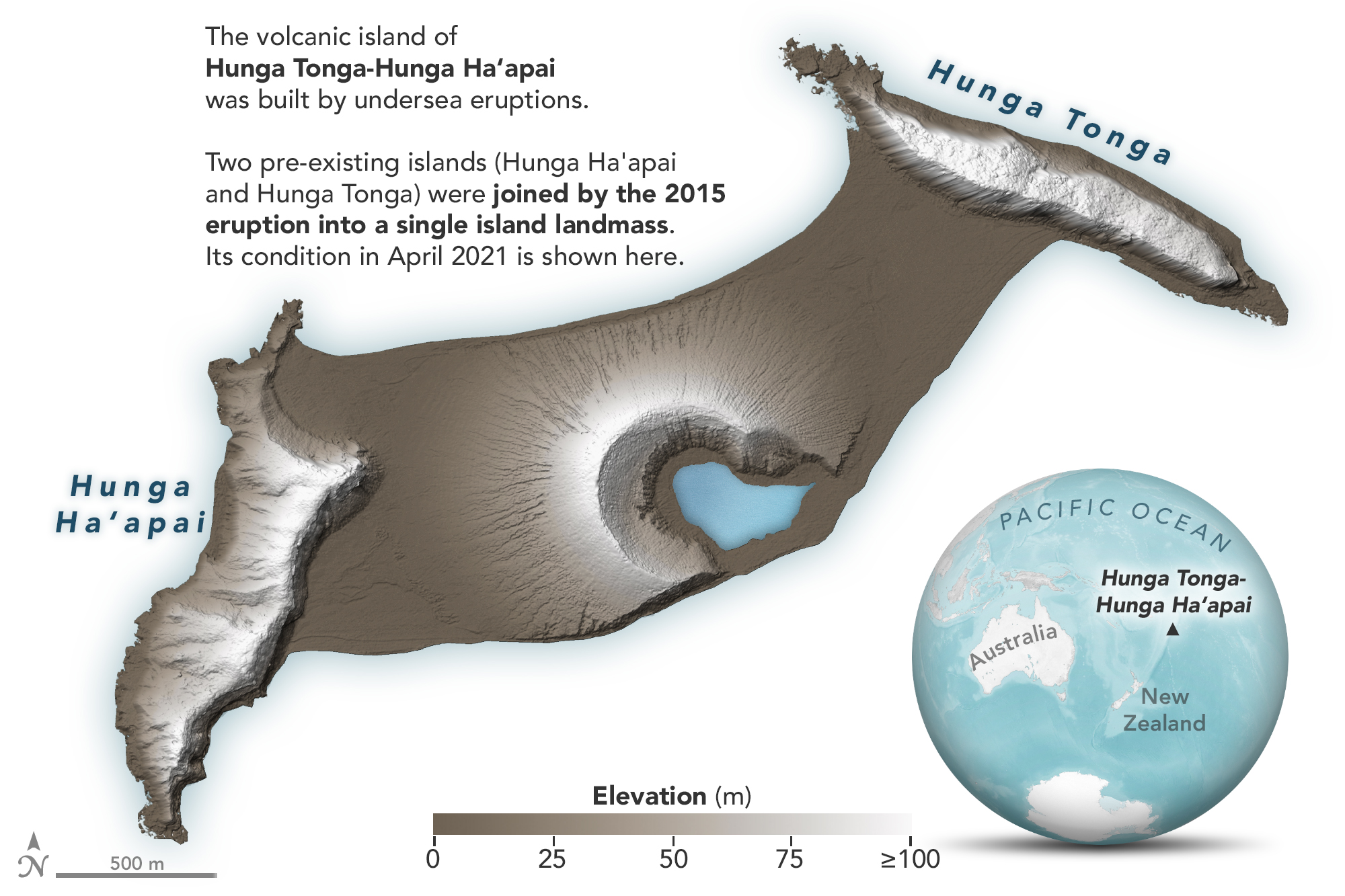

Garvin is part of a team of researchers who have been monitoring the Tonga volcano closely since 2015, when its activity pushed new land above the Pacific waves and joined two small pre-existing islands known as Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha'apai.

The recent eruptions enlarged that newly created island, at least initially.

"By early January, our data showed the island had expanded by about 60% compared to before the December activity started," Garvin said. "The whole island had been completely covered by a tenth of [a] cubic kilometer [0.02 cubic miles] of new ash. All of this was pretty normal, expected behavior, and very exciting to our team."

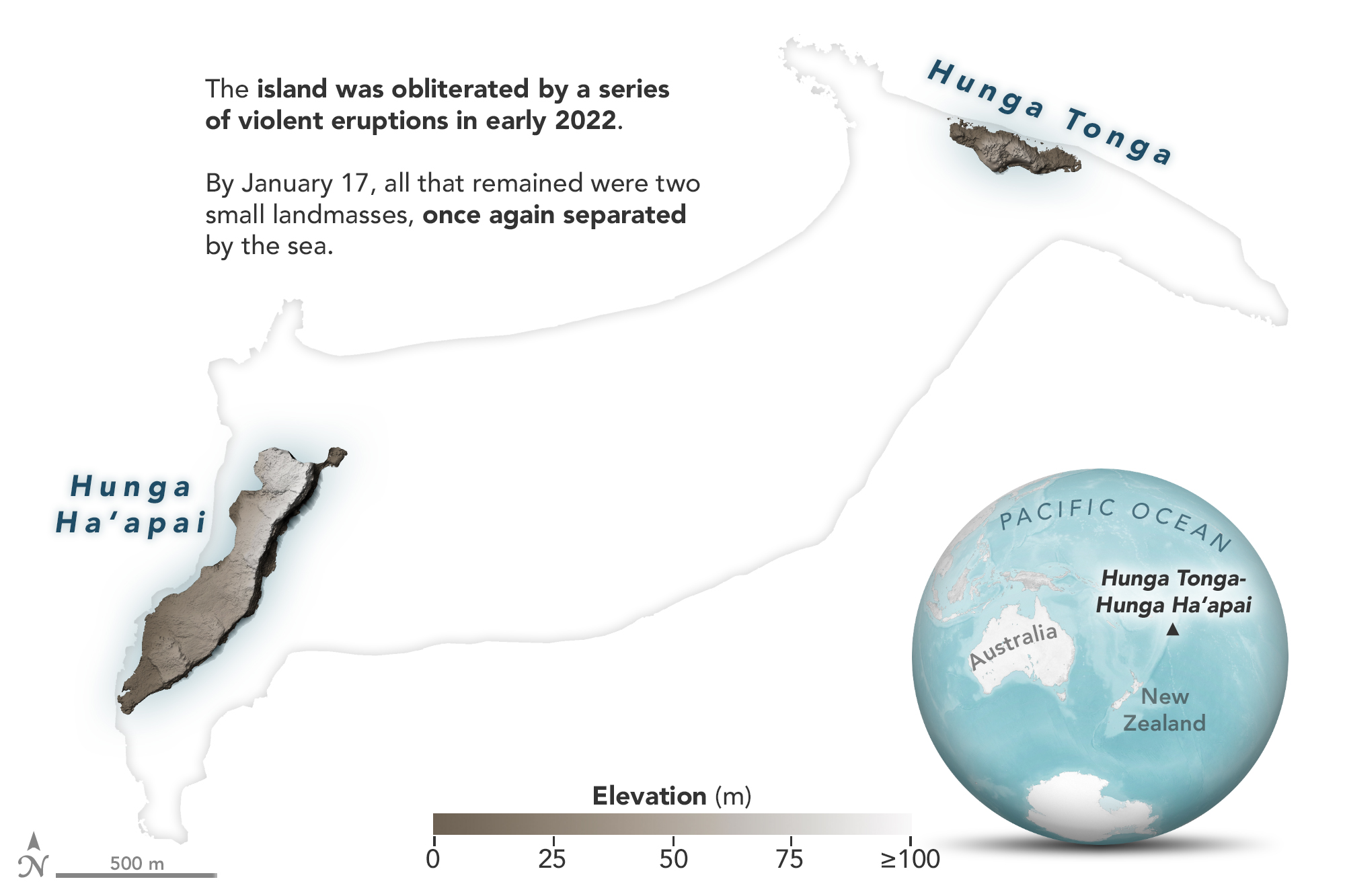

The mid-January eruptions undid this island-building work, however, blasting away the recently created land and leaving small, separated remnants of Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha'apai. Such activity provides more data for Garvin and other researchers to analyze, to help them better understand volcanoes here on Earth and on other worlds as well.

"Small volcanic islands, freshly made, evolving rapidly, are windows [into] the role of surface waters on Mars and how they may have affected similar small volcanic landforms," Garvin said. "We actually see fields of similar-looking features on Mars in several regions."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.