After a tantalizing discovery at Venus, what could an astrobiology mission look like?

Suddenly, a mission to investigate whether Venus might be hospitable to life after all doesn't seem quite so outlandish.

Astronomers announced Monday (Sept. 14) that they have identified phosphine, a chemical some scientists have proposed may be a sign of life, in the clouds of Venus. The new research relied on data from two ground-based telescopes, and scientists already have plans to tug a little more at the Venusian mystery from Earth's surface.

But, if we really want to know what's going on with this strange chemical in the thick, acidic clouds of our planetary neighbor, we're going to need to get a lot closer, even right into Venus' clouds — where no spacecraft has ventured in 35 years.

"This is something more that we can't explain about Venus," Sanjay Limaye, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who wasn't involved in the new study, told Space.com. "Venus has got more questions [about it] than Mars, which is why we are suggesting that Venus should be considered an astrobiology target."

Related: Strange chemical in clouds of Venus defies explanation. Could it be a sign of life?

It's not that scientists haven't wanted to explore Venus more thoroughly, of course. But the planet is seriously rough on the vital organs of a spacecraft. Take a computer, some electronics and a bunch of ultra-sensitive instruments and send them through acidic clouds to a surface that's essentially a broiling pressure cooker, and, well, it isn't pretty. In fact, no spacecraft has ever survived a full two hours on the surface of Venus.

"Venus is ready for the armada to get there, but it's less forgiving than Mars," James Garvin, a planetary scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, who wasn't involved in the new research but is the principal investigator on a Venus atmospheric probe mission that NASA is evaluating, told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

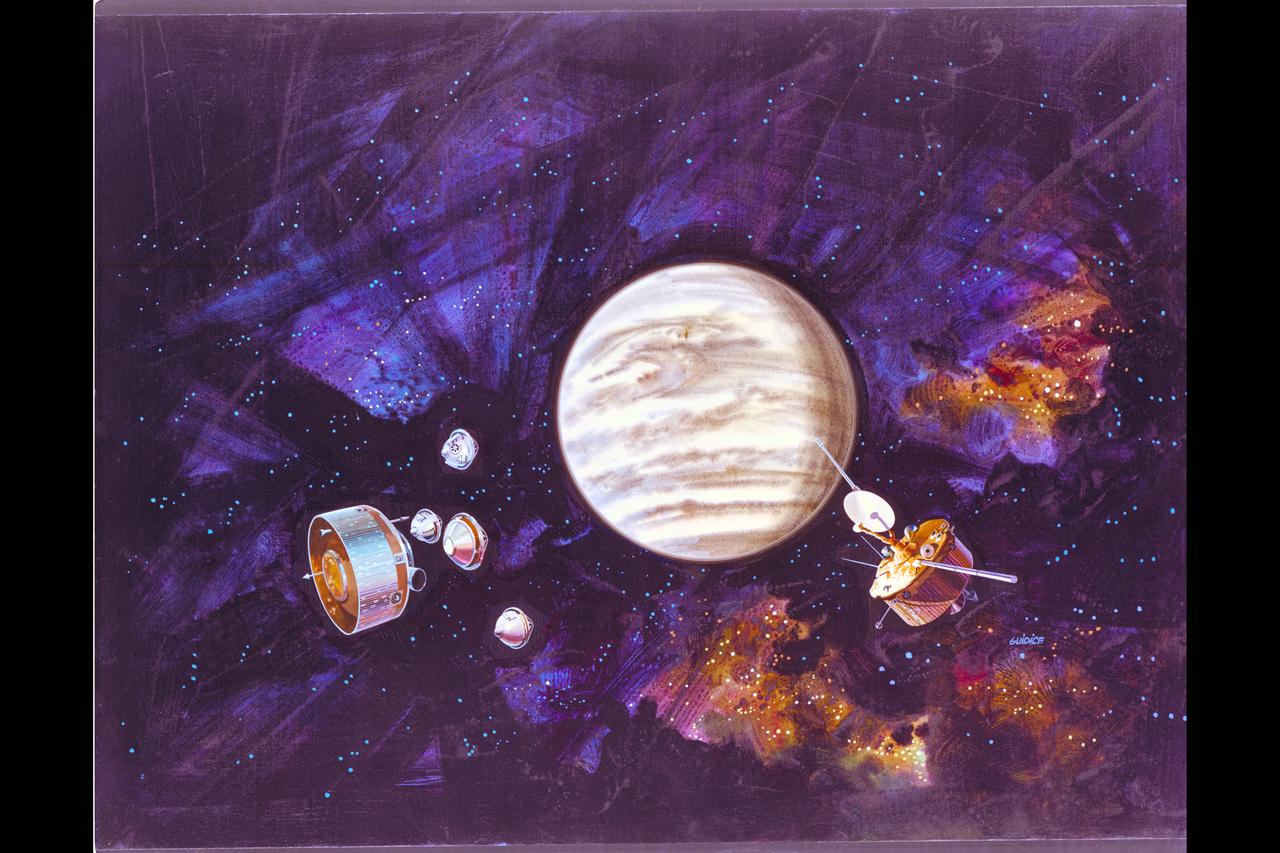

That said, engineers have been busy in the decades since the last spacecraft ventured into Venus' atmosphere when the Soviet Vega probes did so in the mid-1980s. With the added impetus created by the tantalizing new research, scientists hope that agencies may now turn their sights to more — and more daring — Venus missions.

"I think this is catalytic," Garvin said of the potential impact of the new research on the motivation to explore Venus. "After a mad foray, a flourish of attempts to understand Venus in the '70s and early '80s, there was a hiatus and it's actually been 35 years since any mission by any country on this planet has visited the atmosphere of Venus."

Related: Here's every successful Venus mission humanity has ever launched

Back to Venus?

Right now, Venus has just one spacecraft companion, Japan's Akatsuki orbiter. Akatsuki launched in 2010 and, while it flubbed its first attempt to orbit Venus later that year, it succeeded on a second attempt in 2015. The spacecraft has spent its tenure studying the weather on Venus and looking for flashes of lightning — all from a safe orbit, of course.

NASA's, however, hasn't had a dedicated mission to Venus since the Magellan probe orbited from 1990 to 1994. But the new research may prompt NASA to end that drought. "It's time to prioritize Venus," NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine wrote in a tweet on Monday about the phosphine detection, which he called "the most significant development yet in building the case for life off Earth."

NASA is evaluating two Venus-targeted proposals in its current round of so-called Discovery projects, the same class of mission that includes the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, the geophysics InSight lander on Mars and the upcoming asteroid missions Lucy and Psyche.

Other space agencies are also considering a visit. India's space agency is considering a mission called Shukrayaan-1, an orbiter that would launch in 2023 and study Venus' surface. Russia is considering a hardier version of its Soviet-era landers, a longer-lived surface mission. The European Space Agency (ESA) is evaluating a proposal for a mission called EnVision, a geology orbiter that would launch in 2032 and could tell scientists about alternative explanations for the phosphine detection, such as by determining whether the planet hosts active volcanoes that could be producing the gas.

Scientists say that the engineering is ready for such missions, and we long ago hit the point where we had machinery worth sending. "It's so frustrating that we have the technology and have had much of this technology for so long and we're just ready to bring this to bear on Venus now," Darby Dyar, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and the deputy principal investigator on the second mission proposal NASA is currently considering, told Space.com. "Venus offers a smorgasbord of really cool missions that you can do."

There are plenty of other Venus mission concepts out there that aren't formally under agency review, ranging all the way from modest endeavors to NASA's most ambitious (and most expensive) category of projects, on the scale of the agency's sophisticated Mars rovers Curiosity and Perseverance.

But we'll need several spacecraft to really understand the story of Venus. "There's not a single mission," Limaye said. "It's a collection of missions because there are so many different investigations that not a single mission can address all the questions and it'll be a fight to decide which missions should be flown first."

(Venus scientists, even those proposing specific missions, regularly emphasize that because Venus is so understudied, any mission to go there at all would be an improvement over the status quo.)

In the context of the phosphine detection announced this week, there are two ways future missions could build on the new research. Either spacecraft could confirm the detection itself, or they could develop our larger understanding of Venus, helping scientists interpret the detection.

Investigating phosphine up close

The new claim of detecting phosphine at Venus is based only on observations taken by ground-based telescopes, but those observations pose two key challenges.

The first is that there's still a chance the detections weren't actually of phosphine: The scientists studied only a small window of the spectral signature — a sort of chemical barcode, in which the researchers saw only what corresponded to one line of the code. In order to more confidently identify the chemical, scientists will need to be able to see one or more other lines of that signature.

A second challenge is that the telescopes the scientists used can't identify precisely where in Venus' atmosphere the phosphine might be. All scientists know so far is that it must be more than 30 miles (50 kilometers) above the surface of Venus. Without a more precise understanding of the signal's altitude, it's difficult to know what environment the chemical may be in.

Related: The 10 weirdest facts about Venus

Breaking the decades-long drought of atmospheric probes at Venus should help scientists to manage both of those challenges.

"We'd like to see really any kind of mission go back to Venus," Sara Seager, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-author on the new research, said during a news conference held on Monday (Sept. 14). "Something that's capable of measuring gases in the atmosphere, something that has a so-called mass spectrometer that can identify larger complex molecules that could only be associated with life," she said, describing her mission wishlist, adding that a balloon might be the best design for such a spacecraft.

While it isn't a balloon, one of the two missions NASA is currently considering would be equipped to tackle the phosphine mystery head-on, Garvin said of the mission proposal he leads, called DAVINCI+ (short for Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Plus).

DAVINCI+ is a two-part mission that includes a probe that would travel through Venus' entire atmosphere to the planet's surface in about an hour, sampling as it goes, and an orbiter that would study the atmosphere of Venus' daylight side and the terrain of its night side for a full Venusian year, or 225 Earth days.

The probe's descent, in particular, would tell scientists whether the phosphine detection was real and confirm how prevalent the gas is in the Venusian atmosphere. It would also give scientists the thorough understanding of chemistry on Venus that is severely lacking, stymying researchers' attempts to interpret data.

And, while the mission may sound a bit unprecedented, it isn't really, Garvin said. The chemical laboratory at the heart of DAVINCI+ would be essentially the same as those in NASA's Mars Curiosity and Perseverance rovers and the Dragonfly drone that the agency will send to fly on Saturn's strange moon Titan, a mission due to launch in 2026.

"The same way we brought that story to Mars with the Curiosity, and soon Perseverance, rovers; we want to invert that and bring it to the atmosphere, essentially developing a flying sampling rover, that instead of driving, it's flying and falling," Garvin said. "We have to bring the best-instrumented chemistry lab to the samples we want to study in the Venus atmosphere with 21st-century gear."

A step farther

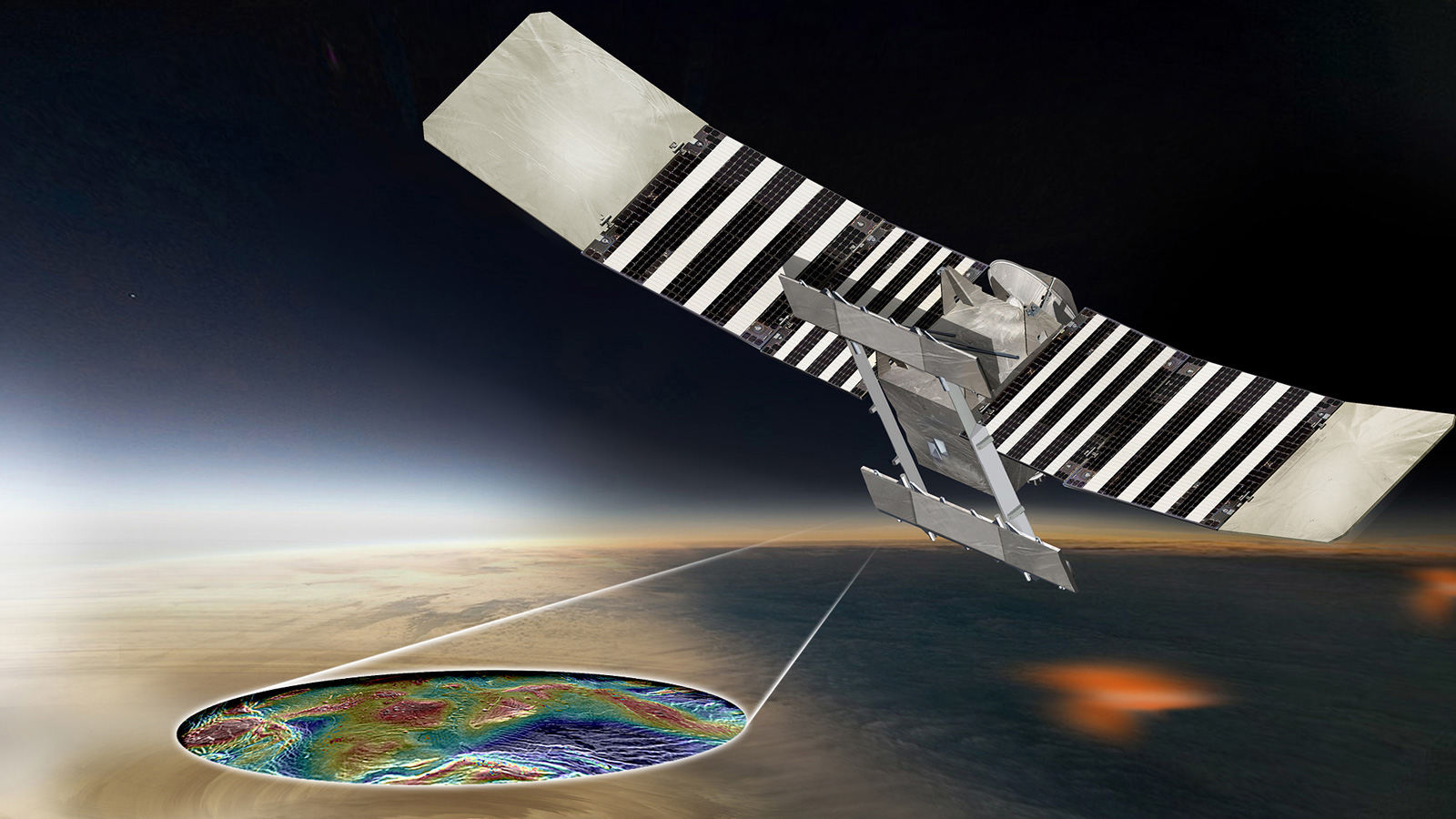

The other Venus mission NASA is currently evaluating could build on the phosphine detection in a different way. VERITAS (short for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy) wouldn't probe the atmosphere directly and wouldn't be able to confirm the phosphine detection up close.

Instead, it's an orbiter that would use radar and spectroscopy to study the surface of Venus. VERITAS is designed to produce a high-resolution topographical map of Venus and identify what types of rocks are found on its surface and where.

"To get the first look at global composition at least is going to tell us so much, even if the method is not everything you might wish for," Sue Smrekar, a planetary geophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and the principal investigator on the VERITAS proposal, told Space.com. "It's going to be, I think, really spectacular in terms of enhancing our understanding of surface chemistry."

The data collected by VERITAS could help scientists address ongoing mysteries like how long Venus had an ocean and how quickly it disappeared, or whether there are still active volcanos spewing chemicals into the planet's atmosphere from its deep innards. Understanding these issues could determine whether the detected phosphine can be explained without invoking life.

VERITAS would also build a foundation for future missions, particularly by mapping the planet's surface in detail. "We've had so much success at NASA having global reconnaissance to find the scientifically most compelling targets and then coming back to follow up," Smrekar said. "Yeah, you need a map," Dyar added.

VERITAS and DAVINCI+ are two of four concepts from which Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate will select one or more missions next spring. Like his boss Bridenstine, Zurbuchen expressed excitement about the new phosphine finding, calling the paper "intriguing," although he was less gung-ho in his remarks.

"We trust in the scientific peer review process & look forward to the robust discussion that will follow its publication," Zurbuchen wrote on Twitter, referencing both the consideration of VERITAS and DAVINCI+, and NASA's involvement in ESA's potential EnVision mission.

One thing is for sure: if these or any other missions visit our neighboring world, Venus scientists will be thrilled.

"The '20s could be a rebirth of using Venus as a clue to the solar system and accessible universe, the same way we've used Mars and the moon and now [Jupiter's moon] Europa so compellingly." Garvin said, adding that he hopes space agencies use this decade to gather the data that has been so sorely lacking about our neighboring world.

"If we can do that in the '20s, the '30s will erupt into this beautiful masterpiece of new kinds of missions: Titan, hopefully also to Venus, Mars, women living on the moon. I mean, it's going to be a different space age." Garvin said. "To be honest, I wouldn't be surprised if we wake up in the '30s and say, 'Oh, my god, how could we have missed this?'"

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

-

Chris Crawford Jeez, people sure are getting carried away by this discovery. There are plenty of ways that phosphine can be made abiologically. The hypothesis that this phosphine is generated by living systems is less plausible than the hypothesis that it is generated by chemical processes lower in the atmosphere and transported up to where we see it.Reply

More important, we must always ask "What is the ESSENCE of the problem?" and the essence of life is negentropy. Life cannot exist without a big supply of negentropy. So what could be the source of negentropy on Venus? Sunlight is the primary source of negentropy, but sunlight doesn't penetrate very far into the Venusian atmosphere, so it is an unlikely source. It is possible that big thermal gradients could supply a small amount of negentropy; that's how the creatures around black smokers deep in our oceans survive. But surface temperatures on Venus are already very high, so there's not much delta-T possible. And of course, big delta-Ts in a gas lead only to convection, not life. It's also possible that some chemical negentropy could be available. We know that some extremophiles on earth survive on chemical negentropy. But this form of life is rare and is unlikely to have evolved directly. -

joover You cite NASA, MIT and others in the US, but not a word about Professor Jane Greaves of Cardiff University, the team leader who made the discovery!Reply -

just_some_dude ReplyChris Crawford said:Jeez, people sure are getting carried away by this discovery. There are plenty of ways that phosphine can be made abiologically. The hypothesis that this phosphine is generated by living systems is less plausible than the hypothesis that it is generated by chemical processes lower in the atmosphere and transported up to where we see it.

IMHO, if people "getting carried away" leads to funding for more probes to investigate the hypotheses, then it's a good thing.

I'm not sure what you mean by negentropy in this context , but it has been suggested that UV from the sun could be an energy source for atmospheric life. I'm not in a position to argue either way, but I'm glad to hear people are getting excited. -

Chris Crawford Wouldn't it be better if precious funding for space projects was given to the investigations that held the greatest promise of interesting results? If this phosphine hypothesis be false, as seems likely, then we'd be wasting money following up on it. There are so many worthy investigations that can't get funding, we really need to be careful about how we spend our money.Reply

UV from the sun is not a primary source of negentropy; most of the negentropy is in the visible spectrum. Negentropy is a concept from thermodynamics. It's a confusing concept for most people, but in fact, it is the essence of life. All living systems, here or elsewhere, must be negentropy harvesting machines. -

just_some_dude Sure, but what's more promising than Venus at the moment, not already being investigated, and within technological reach? Also, people "getting carried away" can lead to MORE funding for space projects.Reply

Regarding negentropy, the only source I really found on that was this line from Wikipedia: "In his book, Schrödinger originally stated that life feeds on negative entropy, or negentropy as it is sometimes called, but in a later edition corrected himself in response to complaints and stated that the true source is free energy. " -

Chris Crawford Yes, Venus is a tantalizing target. It's also a very difficult target, because of the extremely high temperatures. The probes we have sent down to the surface all lasted a few minutes before failing. Sure, we can make metals that can handle those temperatures, but how do we build electronics capable of functioning at those temperatures? So far, the best we can do is get something that can operate for a few minutes longer before failing. Perhaps something with extremely low thermal conductivity (think of the tiles on the bottom of the Space Shuttle) enclosing the electronics could keep it from frying for a little while. But how do the sensors work? To sense the environment, they have to BE in the environment. Nasty, nasty problem. This is why we know so little about the surface of Venus.Reply

More promising would be studies of its atmosphere, which is not so hellishly hot. Indeed, there have been a number of proposals for balloons that float high in the Venusian atmosphere. It's crucial, however, to understand the vertical structure of the atmosphere, and that requires a balloon that can move vertically, dipping down into lower, hotter regions. Moreover, any such system would be vulnerable to high wind velocities.

Yes, Schrodinger's 1944 lecture is considered to be one of the landmarks. You can download the PDF here. You can also search the web for phrases like "negentropy and life" or "entropy and life". I warn you, this is heavy stuff; you'll have to knuckle down and read carefully. -

mbee1 Reply

Sunlight does not penetrate into very far into the atmosphere? That is simply not true. The russian probes took pictures of the surface when they landed so sunlight is there. The problem is not sunlight it is the lack of water and the heat which might be solved if the life was floating around in the clouds which of course does not tell us how it got there.Chris Crawford said:Jeez, people sure are getting carried away by this discovery. There are plenty of ways that phosphine can be made abiologically. The hypothesis that this phosphine is generated by living systems is less plausible than the hypothesis that it is generated by chemical processes lower in the atmosphere and transported up to where we see it.

More important, we must always ask "What is the ESSENCE of the problem?" and the essence of life is negentropy. Life cannot exist without a big supply of negentropy. So what could be the source of negentropy on Venus? Sunlight is the primary source of negentropy, but sunlight doesn't penetrate very far into the Venusian atmosphere, so it is an unlikely source. It is possible that big thermal gradients could supply a small amount of negentropy; that's how the creatures around black smokers deep in our oceans survive. But surface temperatures on Venus are already very high, so there's not much delta-T possible. And of course, big delta-Ts in a gas lead only to convection, not life. It's also possible that some chemical negentropy could be available. We know that some extremophiles on earth survive on chemical negentropy. But this form of life is rare and is unlikely to have evolved directly. -

Chris Crawford Um, have you considered the fact that we cannot see the surface of Venus from earth? If little light from the surface gets OUT, then how much do you think gets IN? Yes, sunlight gets through -- but it's nowhere near as much sunlight as reaches the surface of the earth, even though we're further away. Look at some of the photos from the surface. Yes, there's light, but there's almost nothing in the way of shadows. The light is greatly diffused, which in turn reduces its negentropy.Reply

Moreover, the delta-T on Venus is smaller than on earth. With surface temperatures of about 750ºK (as opposed to 300ºK on the surface of the earth), there's less negentropy to harvest. Lastly,

The absence of water is irrelevant; theoretically, you can have plenty of life without any water at all. Earth's life is based on chemical reactions taking place in water, but there are many other ways to harvest negentropy.

It would be extremely difficult for living systems to form in a gas. Not impossible, but you'd need a LOT of negentropy to drive that process. -

just_some_dude ReplyChris Crawford said:It would be extremely difficult for living systems to form in a gas.

Maybe they didn't originally form where they are today? /venus-life-earth-grazing-asteroid