Venus May Not Have Been As Earthlike As Scientists Thought

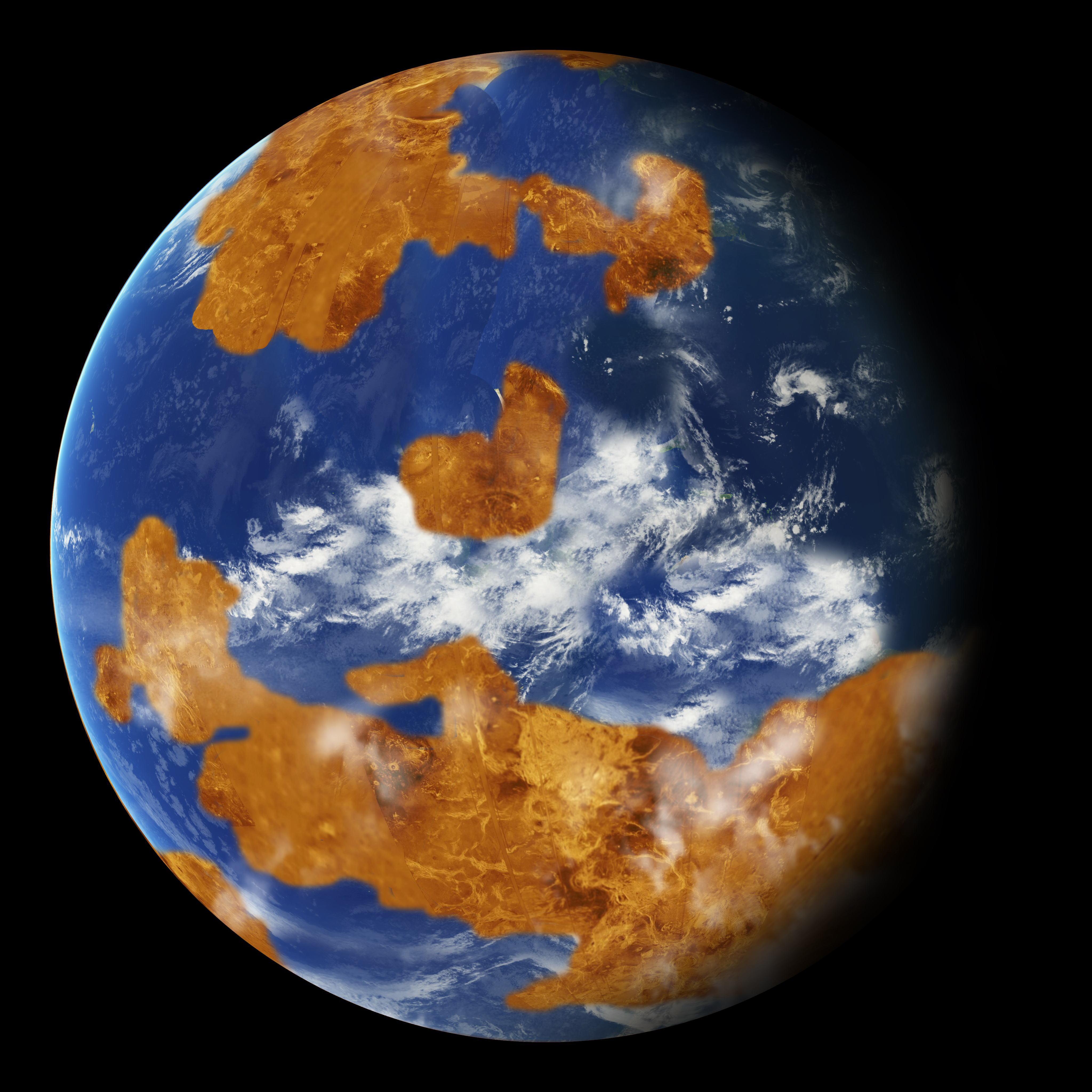

Was Venus once covered in a liquid water ocean? A new study suggests it was not, which could diminish hope that eons ago, warm and wet conditions allowed life to arise on the planet.

Today, Venus' climate is far from temperate. The planet is completely shielded by clouds and has a hell-like surface; a runaway greenhouse gas effect makes for lead-melting temperatures of more than 700 degrees Fahrenheit (370 degrees Celsius).

But some scientists argue that the requirements for life could have existed on Venus earlier in the solar system's history. Venus is roughly the same size and mass as Earth and even had plate tectonics. The sun was also dimmer during that epoch, so Venus, despite being closer to the sun than Earth is, was in the habitable zone, or the region where a rocky planet could have liquid water on its surface.

Related: Can Venus Teach Us to Take Climate Change Seriously?

Some scientists suggest that habitability vanished when the sun's radiation grew stronger, causing the Venusian oceans to evaporate and water molecules to be thrown into the atmosphere. Water vapor is a greenhouse gas that would have made it harder for heat to escape from the planet. The wet atmosphere began a cycle of rising temperatures, evaporating oceans and increasing water vapor that made temperatures rise even further.

In September, researchers from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies released simulations of several scenarios that would allow liquid water to exist at the surface for millions of years, before this runaway effect occurred.

But the new study suggests that such water oceans were never there in the first place. While previous work hinted at a warm and wet environment based on the chemistry of the atmosphere and the higher regions of Venus, the new research suggests the highlands were made of lava rather than water.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This finding comes down to the composition of the highland rock. Previously, scientists thought the highlands were made up of granitic rock, just like continents on Earth. Granite needs a lot of water to form. But a survey of Venus' Ovda Regio highlands plateau — remapped with radar data gathered by NASA's Magellan mission, which studied Venus between 1989 and 1994 — shows the flow type is more typical of basalt rock.

"We know so little about Venus' surface," team member Allan Treiman, a Universities Space Research Association scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute, said in a statement. "If the Ovda Regio highlands are made of basaltic rock as is most of Venus, they were likely squeezed up to their current heights by internal forces, possibly like mountains which result from plate tectonics on Earth."

A study based on the research was published Aug. 9 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

- The Strange Case of Missing Lightning at Venus

- Should We Land on Venus Again? Scientists Are Trying to Decide

- Life on Venus? Why It's Not an Absurd Thought

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.