10 phenomena to see and photograph during a total solar eclipse

From 'shadow snakes' and 'double diamonds' to Baily's beads and the corona, here's what you need to prepare for and the gear you need to see it.

Everyone knows what the highlight of experiencing a total solar eclipse is. For a few fleeting minutes or seconds, it's possible to see, with the sun's disk completely blocked by the moon, our star's outer atmosphere — the corona. It's possible to see, under a suddenly darkened sky and with the naked eye — the whitish corona's filaments and tendrils shoot off into space. It's like seeing the sun for the first time, and as it truly is — as a star floating against the blackness of space.

Totality, however, may be the visual, experiential, and photographic highlight of a total solar eclipse, but it's far from the only thing to experience. Here's what not to miss during the entire partial phases and totality.

Be sure to also find out about the strange eclipse phenomena and all the stages of the total solar eclipse before it joins you in your area.

Solar eclipse kit deals June 2025

- Amazon: Celestron solar eclipse glasses

- B&H Photo Video: Binoculars, glasses and telescopes

- Adorama: Solar glasses, filters, binoculars and cameras

- Best Buy: Solar eclipse power viewers

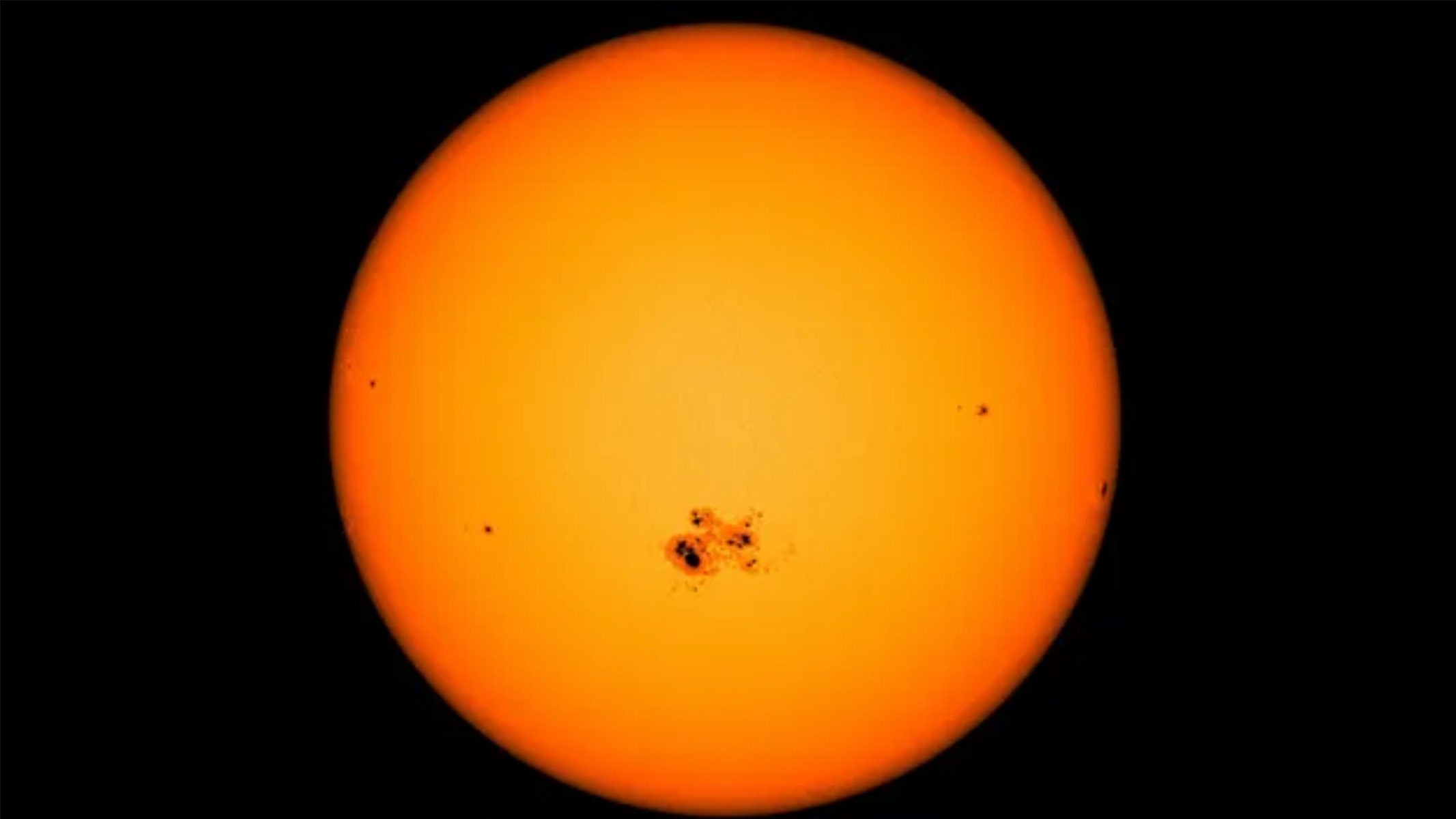

1. Sunspots

As luck would have it, the sun is currently close to solar maximum. This once-every-11-years peak in magnetic activity means there are black sunspots (areas of intense magnetic activity) on its surface almost every day, typically around its equator. Use your solar eclipse glasses, solar telescope or solar binoculars to get a great view of them close to the limb of the moon as it gradually swallows them.

- Read our Celestron EclipSmart 10x25mm roof solar binoculars review

- Read our Celestron EclipSmart 12x50mm porro solar binoculars review

2. Pinhole projections

Before there were solar eclipse glasses and filters, the only way to follow the partial phases of any solar eclipse was to use the pinhole projection method. It works like this: sunlight enters a pinhole and is focused before being projected out of the other side. Put a piece of paper or card in its way, and you'll see an image of an eclipsed sun. Pinhole projection cameras can be made using cardboard boxes, while eclipse projectors — with added magnification — require using binoculars or a telescope pointed at the sun (though avoid anything with electronics in them — they will heat up!). Photographs of people using these awkward-looking contraptions can be memorable.

3. Crescent suns

About 40 minutes after first contact, look around for crescent suns projected onto floors, walls and people. Visible when the sun is approximately 50% eclipsed by the moon, anything with small, defined holes will help create this effect. Spaghetti spoons and colanders are perfect for the job, but so are cards attached with a hole punch. You can even cross the fingers of your hands to create crescent suns, while the canopies of trees can also project carpets of crescent suns across the ground. These are the kinds of images missed by most eclipse photographers focused only on the eclipse itself.

4. Shadow of the moon

There's so much going on as totality begins, but this one is typically forgotten. Darkness will fall quickly as the edge of the moon's shadow reaches your location, traveling between 1,000 and 5,000 mph, depending on where you are along the path of totality. Can you see it coming? Then departing a few minutes later? It's possible to see and capture it on video if you're up somewhere high, perhaps at an overlook or on a mountainside above a valley. It's more prominent under a cloudy sky, so it may be something to try for if the weather is an issue where you are.

5. Purkinje effect

During a solar eclipse, the human eye becomes more sensitive to blue light as the light gradually diminishes. Consequently, the color red appears dull and weird-looking. This phenomenon is known as the 'Purkinje effect' and occurs approximately four minutes before second contact and totality. Consider wearing reds and greens — they're the colors that look downright odd in the otherworldly minutes before totality.

6. Shadow bands

In the last minute or so before totality, the 1% of the sun left uncovered is still enough to illuminate your surroundings, but it's struggling. Earth's atmospheric turbulence refracts the weak light of the crescent sun, the same phenomenon that makes stars twinkle. It causes ripples of light to move quickly, with light-colored surfaces such as walls and vehicles catching them best. At some eclipses, shadow bands can cause a 'woah!' moment; at others, they're barely visible. Don't try to photograph or video them because the results will be poor — just watch.

7. Baily's beads

With second contact imminent and the light level crashing around you, beads of light will begin to fizz around the limb of the moon as the final slit of sunlight dissolves into nothing. They are named Baily's beads after the astronomer who named them during an annular solar eclipse in the U.K. in 1836. These shrinking points of light are sunlight streaming through the valleys and mountains of the moon. They're also visible just as totality ends at third contact, which is the best time to see them (seeing them before totality can dazzle your eyes).

8. Diamond ring

Another phenomenon that occurs just before totality, but is best left for its second appearance at the end of totality, is the diamond ring. It's one large Baily's bead, which makes the moon look like a ring with a shiny diamond. It's dangerous to look at it for a long time, but that's not really a concern as it only lasts a millisecond. Its appearance at the end of totality signals third contact and the end of naked-eye views of the eclipse. It's time to put the solar eclipse glasses back on or, more likely, crack open the champagne.

9. Solar Corona

This is what you've been waiting for. As Baily's beads diminish to nothing at the beginning of totality, the light disappears, and the sun's outer atmosphere is instantly revealed. What a sight! Its diffuse, whitish light is usually hidden because the sun's visible light from its photosphere is a million times brighter. You can look intensely at the corona with your naked eyes since it's no brighter than a full moon. Try looking at it with eclipse glasses, and you'll see nothing! If you have a pair of binoculars, use them — it will be the absolute sight of your life. While you do, look out for pinkish prominences explosions on the sun's surface — which will almost certainly be visible during totality.

10. Planets and Comet Pons-Brooks

Will a comet be visible during totality? Perhaps. Orbiting the sun every 71 years, Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks will next get closest to the sun on April 21, 2024. That's handy timing for eclipse-chasers, though it is not expected to get brighter than magnitude +4.7, which is on the cusp of naked eye visibility at night. To complicate things, totality probably won't be as dark as night. Pons-Brooks will be 27-degrees from the sun and close to the bright planet Jupiter to the upper-left of the eclipse, which will also be visible. Venus, meanwhile, will shine very brightly to the lower right of the eclipse.

When is the next solar eclipse?

The next solar eclipse will take place on October 2 and it will be an annular eclipse. If you're interested in photographing this rare event, take a look at our how to photograph the total solar eclipse guide. Always remember to make sure you are viewing the sun safely.

Keep up to date with the latest eclipse content on our eclipse live blog and watch all the total eclipse action unfold live here on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jamie is an experienced science, technology and travel journalist and stargazer who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com and author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, and is a senior contributor at Forbes. His special skill is turning tech-babble into plain English.