Shuttle Delivers $2 Billion Astrophysics Experiment to Space Station

HOUSTON — The International Space Station is about to get a major upgrade: a $2 billion astrophysics experiment to hunt for invisible cosmic rays and, in turn, search for new clues into antimatter and elusive dark matter.

The instrument, called the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, launched toward the station on Monday (May 16) aboard NASA's Endeavour on the shuttle's final mission. The shuttle arrived at the station today with the spectrometer packed in its cargo bay. [Photos of Shuttle Endeavour's Final Launch]

Endeavour's six astronauts will attach the massive spectrometer (it weighs 7 tons) to the space station's exterior tomorrow (May 19) as part of their mission to deliver new gear and supplies.

Unprecedented experiment

The AMS is the most expensive science experiment ever flown on the station. It represents 17 years of work by scientists in 16 countries. [Video: Sifting Cosmic Sand for Dark Matter]

It represents one of the most fundamental human drives: curiosity, according to the instrument's principal investigator, Nobel laureate Samuel Ting of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"The difference between humans and animals is curiosity," Ting told SPACE.com. "It's curiosity that drives a physicist forward to search for the unknown."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Huge magnet

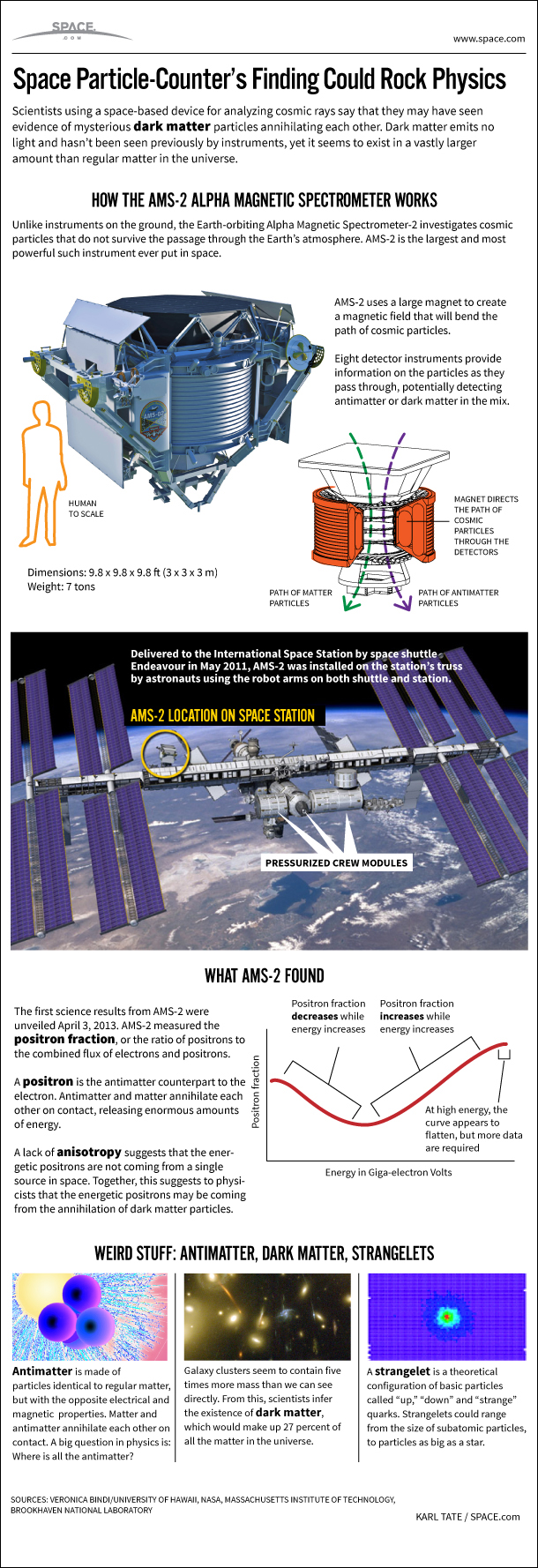

The bus-sized experiment houses a 3-foot (1-meter) wide magnet that will bend the paths of cosmic ray particles flying through space, sending them into special detectors that will measure their properties. [Infographic: How the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer Works]

"It's a particle detector," Endeavour's pilot, Greg H. Johnson, said in a preflight NASA interview. "It collects various cosmic particles that can't come through our atmosphere to Earth, so this particular experiment can't be on the surface of the planet."

Scientists hope these particles will include exotic species such as antimatter and even strange matter, which contains rare particles called strange quarks. AMS will also search for signs of the elusive dark matter scientists suspect permeates space, but have yet to detect directly. [Q&A with AMS Principal Investigator Sam Ting]

But the most exciting discoveries of AMS could turn out to be the ones scientists haven't even thought to predict.

"You set up these scientific experiments … and you end up learning something that you didn't expect," Gary Horlacher, the shuttle's lead flight director, said told reporters today. "Hubble's done that, all the great observatories have ended up surprising us. Just like Hubble, I expect it to rewrite our textbooks for a long time."

The experiment almost never got the chance to fly. After the 2003 space shuttle Columbia accident, the flight slated to launch AMS was cancelled. It took lobbying by hundreds of scientists, and a bill passed by Congress, to add one more space shuttle mission to launch AMS.

Tricky installation

The installation of the experiment will begin with astronauts Drew Feustel and Roberto Vittori controlling the space shuttle Endeavour's robotic arm, called Canadarm 2, to grab onto AMS and lift it out of the orbiter's payload bay. Then the astronauts will hand the instrument off to their crewmates, Greg Chamitoff and Greg H. Johnson, controlling the space station's robotic arm.

The overall maneuver to transfer AMS from shuttle to station is set to begin at 1:56 a.m. EDT (0556 GMT) on Thursday, and complete at 3:41 a.m. EDT (0741 GMT). The station arm will attach to the AMS and carry it over to its permanent destination on the lab's starboard-side truss, or backbone.

"It takes quite a few hours; it’s a tricky operation," Chamitoff said in a preflight NASA interview. He pointed out that the attachment mechanism used to install the AMS doesn't have the same level of redundancy, or backup equipment, in place in case it fails. "I'll be breathing a little better after that's been completed and I know that it's attached successfully, just because we don't have the redundancy there if something does go wrong."

The instrument will be turned on shortly after installation, and should begin recording data that same day. Results from the experiment, however, won't be available for months because scientists will need time to collect and analyze its many measurements.

Shuttle heat shield dings eyed

While the shuttle crew will be focused on AMS Thursday, some mission managers will be investigating a few small patches of damage discovered in the shuttle's heat shield.

The patches were revealed by a detailed scan of the heat shield tiles conducted by the astronauts on their first full day of space on Tuesday, as well as by high-resolution photos of the shuttle's underbelly made during a special maneuver today as Endeavour approached the International Space Station before docking.

The largest of the areas measures almost 7 inches (18 cm) across.

"This is not cause for alarm, this is not cause for any concern," LeRoy Cain, chair of the shuttle's mission management team told reporters Wednesday. "We haven't done enough work yet to be able to determine whether or not there's any more information or assessment we need. We're in the throes of doing that work right now."

If more data is needed to assess whether or not the damaged tiles pose any threat to the shuttle during re-entry to Earth, mission managers may elect to have the astronauts conduct an optional second inspection later on in the mission.

Endeavour is in the midst of a 16-day mission to deliver the AMS and other equipment to the International Space Station. The mission is the 25th and final spaceflight for the shuttle before it is retired this year along with the rest of NASA's orbiter fleet.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Visit SPACE.com for complete coverage of Endeavour's final mission STS-134 or follow us @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.