Fixing the Hubble Space Telescope: A timeline of NASA's shuttle servicing missions

Just because your space telescope is serviceable doesn't mean it's easy to service.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a masterwork of engineering and human ingenuity. Hubble is comparable in size and weight to a large school bus, but its contributions to science and astronomy could fill libraries.

Not only is Hubble one of Earth's premium sources for absolutely incredible, out-of-this-world imagery, it is also a testament to human curiosity and determination. The telescope has been in operation for over 30 years, undergone a total of five servicing missions and delivered nearly 250 terabytes of data in contributions to our understanding of the universe.

Scientists began working on ideas for a large space telescope in orbit by the end of the 1960s, but it would take nearly a decade of lobbying and refining plans before funding for the project was approved by the U.S. Congress. It was almost another half a decade after that before the telescope received its official name — after famed American astronomer Edwin Hubble. Then, due to the loss of Challenger in January 1986 and the ensuing pause of the space shuttle program, Hubble would wait yet another five years before reaching orbit.

Deployment

Loren J. Shriver, commander

Charles F. Bolden, pilot

Steven A. Hawley, mission specialist

Bruce McCandless, mission specialist

Kathryn D. Sullivan, mission specialist

Hubble was built with a number of instruments onboard, including the Wide Field Planetary Camera (WFPC), the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph (GHRS), the Faint Object Camera (FOC), the Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS) and the High Speed Photometer (HSP).

Hubble launched on April 24, 1990, stowed inside the cargo bay of space shuttle Discovery. STS-31 was Discovery's 10th launch, and it was the 35th space shuttle mission overall.

Related: NASA's space shuttle: The first reusable spacecraft

One day after reaching orbit (April 25), the STS-31 crew deployed Hubble, and then spent most of the duration of their mission bringing the telescope into operation. Discovery returned to Earth on April 29, leaving Hubble in an orbit 380 miles (612 kilometers) in altitude, where it could begin awing humanity with the secrets of the universe.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

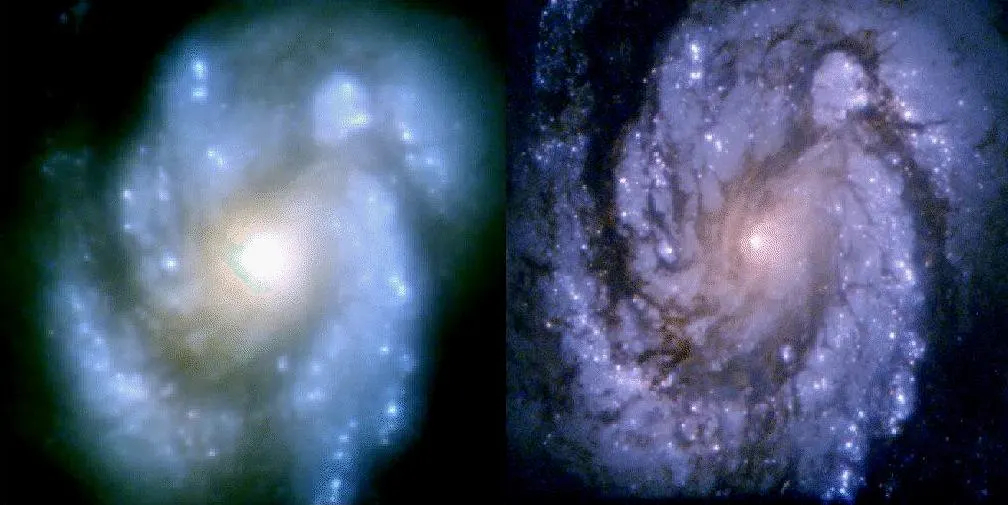

At least, that's what was supposed to happen. But the first images beamed back to Earth from Hubble — NASA's $1.5 billion space telescope that took three decades to reach space — were blurry.

In June 1990, NASA announced the discovery of a spherical aberration on Hubble's primary mirror due to a 2-micron mistake in the curvature of the telescope's primary mirror — about 1/50 the width of a human hair. Though small, the defect made the telescope mostly useless to astronomers. Thankfully, Hubble was designed to be serviceable, and NASA's best minds took to the task.

Servicing Mission 1

NASA's space shuttle Endeavour launched on Dec. 2, 1993 on the STS-61 mission. The goal was to fix the debilitated space telescope so it could finally start seeing straight.

Richard Covey, mission commander

Kenneth Bowersox, pilot

Kathryn Thornton, mission specialist

F. Story Musgrave, mission specialist

Claude Nicollier, mission specialist

Hubble's engineers designed the telescope specifically to be upgraded. Its large body features handrails for astronauts to perform maintenance and modular components to facilitate upgrades with the evolution of technology. This allowed NASA to design and plan fixes to bring Hubble back into operation after its disastrous start.

The STS-61 astronauts aboard Endeavor during Hubble's first servicing mission (SM1) spent more than 35 hours across a total of five spacewalks, or EVAs (extravehicular activity) over the course of as many days to complete their planned upgrades. They installed the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR) unit in place of the HSP — akin to Hubble getting a new pair of glasses to bring its blurry vision into focus. The WFPC was replaced with the WFPC2, which came with internal corrective optics, and Hubble's solar arrays and gyroscopes were upgraded to improve the telescope's tracking ability.

The SM1 mission restored Hubble to operational status, and as a result, produced one of the telescope's most iconic images.

Related: 30 years ago, astronauts saved the Hubble Space Telescope

Servicing Mission 2

Discovery lifted off on the STS-82 mission from Launch Complex-39A, at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, on Feb. 11, 1997. During the 10-day flight, five EVAs were performed to complete the upgrades made to Hubble.

Kenneth Bowersox, mission commander

Scott Horowitz, pilot

Joseph Tanner, mission specialist

Steven Hawley, mission specialist

Gregory Harbaugh, mission specialist

Mark Lee, mission specialist

Steven Smith, mission specialist

Hubble's second servicing mission, SM2, was less reparative and more focused on what engineers had intended when they designed the telescope to be serviceable: upgrades and boosting performance.

Discovery launched on STS-82 in February 1997, with two new instruments for Hubble. The Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) and Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) replaced Hubble's GHRS and FOS. The swap expanded the telescope's vision into near-infrared wavelengths. The mission was also successful in trading out some of Hubble's degraded data recorders, as well as some other, secondary hardware.

Servicing Mission 3A

Discovery's third mission to Hubble was an unexpected one. In November 1999, the fourth of six gyros used to maintain the telescope's orientation failed, sending Hubble into a protective "safe mode." Previous gyros had failed as well, but in order to continue effectively collecting science data, at least three needed to be in working order.

Curtis Brown, mission commander

Scott Kelly, pilot

Jean-Francois Clervoy, mission specialist

Michael Foale, mission specialist

John Grunsfeld, mission specialist

Steven Smith, mission specialist

Claude Nicollier, mission specialist

What was originally scheduled in June 2000 as Servicing Mission 3 (SM3) was split into two missions: An emergency SM3A mission was created for space shuttle Discovery, and STS-102 was added to the launch manifest for December 1999.

Many of the mission's spacewalks exceeded eight hours, making them some of the longest EVAs in shuttle history. During those extended stints navigating Hubble's handrails, NASA astronauts Steven Smith and John Grunsfeld replaced all six gyroscopes inside the telescope's Rate Sensor Unites (RSUs) and installed a new transmitter and data recorder.

During a different EVA, NASA astronauts Michael Foale and Claude Nicollier replaced Hubble's main computer, increasing its processing speed by almost 20 times. They also upgraded Hubble's fine guidance sensors.

Servicing Mission 3B

The splitting up of SM3 into SM3A and SM3B pushed the maintenance scheduled for June 2000 back to March 2002. Space shuttle Columbia launched STS-109 on March 1, with the primary goal of delivering and installing the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS).

Scott Altman, mission commander

Duane Carey, pilot

John Grunsfeld, payload commander and mission specialist

Nancy Currie, mission specialist

Richard Linnehan, mission specialist

James Newman, mission specialist

Michael Massimino, mission specialist

Hubble's ACS replaced the aging FOC, adding 10 times the imaging power compared to that of its predecessor. Astronauts on SM3B were also tasked with replacing Hubble's solar arrays, which had been worn by years of radiation and debris.

Though smaller, Hubble's new solar arrays provided between 20% and 30% more power. They also replaced Hubble's Power Control Unit (PCU) and added a new cooling system to increase the lifespan of NICMOS.

Servicing Mission 4

STS-125 was the last mission to Hubble. With the space shuttle set to retire two years later, Hubble's SM4 aimed to upgrade the space telescope with the technologies to help it last into the 21st century.

Scott Altman, mission commander

Gregory Johnson, pilot

Michael Good, mission specialist

Megan McArthur, mission specialist

Andrew Feustel, mission specialist

Michael Massimino, mission specialist

John Grunsfeld, mission specialist

Space shuttle Atlantis launched on May 11, 2009, carrying two new instruments for the space telescope: the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) and Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3).

When astronauts replaced the FOC during SM3B, the COSTAR instrument that served as Hubble's glasses became redundant. COS replaced COSTAR during SM4 and became a complement to STIS. Where COS's ultraviolet spectrum detection falls off, STIS can pick up in ultraviolet wavelengths through optical to near-infrared light. The astronauts also managed to repair STIS, which had been inoperable since August 2004, when a failure of its power supply sent it into "safe mode."

Some of Hubble's most iconic imagery, including the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, is attributed to the ACS. In 2007, however, it also suffered an electrical failure. Remedies for STIS and ACS were both similar to each other in the tasks astronauts needed to perform to complete their repairs, but were both very dissimilar to how and where engineers expected astronauts to be performing maintenance on Hubble.

NASA astronauts — including John Grunsfeld, who had already participated in three Hubble servicing missions — trained for two years to develop the tools, strategies and techniques they would need to successfully repair the space telescope for the last time.

Hubble today

In the more than a decade and a half since astronauts last visited Hubble, the telescope has continued to provide amazing views of the cosmos, but its operation has not been without its hiccups. As Hubble has aged, NASA mission managers have tightened their operating constraints, deriving strategies for the observatory to continue functioning despite several issues.

As new gyros installed during servicing missions aged and failed, technicians built deeper margins into the components' parameters. Today, the telescope has two functioning gyros and has been shifted to a one-gyro mode to preserve the other as backup. This presents limitations on some of the science and observations Hubble can make but has allowed the famed scope to continue probing the mysteries of the universe.

NASA hopes the new operating parameters will extend Hubble's life into the 2030s. However, that will likely be the end of the road for the space telescope, functioning instruments or not. Without a boost to its altitude from a visiting spacecraft, Hubble will dip into a lower and lower orbit and eventually burn up in Earth's atmosphere by the mid-2030s.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Josh Dinner is the Staff Writer for Spaceflight at Space.com. He is a writer and photographer with a passion for science and space exploration, and has been working the space beat since 2016. Josh has covered the evolution of NASA's commercial spaceflight partnerships and crewed missions from the Space Coast, as well as NASA science missions and more. He also enjoys building 1:144-scale model rockets and human-flown spacecraft. Find some of Josh's launch photography on Instagram and his website, and follow him on X, where he mostly posts in haiku.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.