Sun's Fading Spots Signal Big Drop in Solar Activity

This story was updated at 3:54 p.m. EDT.

Some unusual solar readings, including fading sunspots and weakening magnetic activity near the poles, could be indications that our sun is preparing to be less active in the coming years.

The results of three separate studies seem to show that even as the current sunspot cycle swells toward the solar maximum, the sun could be heading into a more-dormant period, with activity during the next 11-year sunspot cycle greatly reduced or even eliminated.

The results of the new studies were announced today (June 14) at the annual meeting of the solar physics division of the American Astronomical Society, which is being held this week at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces.

"The solar cycle may be going into a hiatus," Frank Hill, associate director of the National Solar Observatory's Solar Synoptic Network, said in a news briefing today (June 14).

The studies looked at a missing jet stream in the solar interior, fading sunspots on the sun's visible surface, and changes in the corona and near the poles. [Photos: Sunspots on Earth's Star]

"This is highly unusual and unexpected," Hill said. "But the fact that three completely different views of the sun point in the same direction is a powerful indicator that the sunspot cycle may be going into hibernation."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

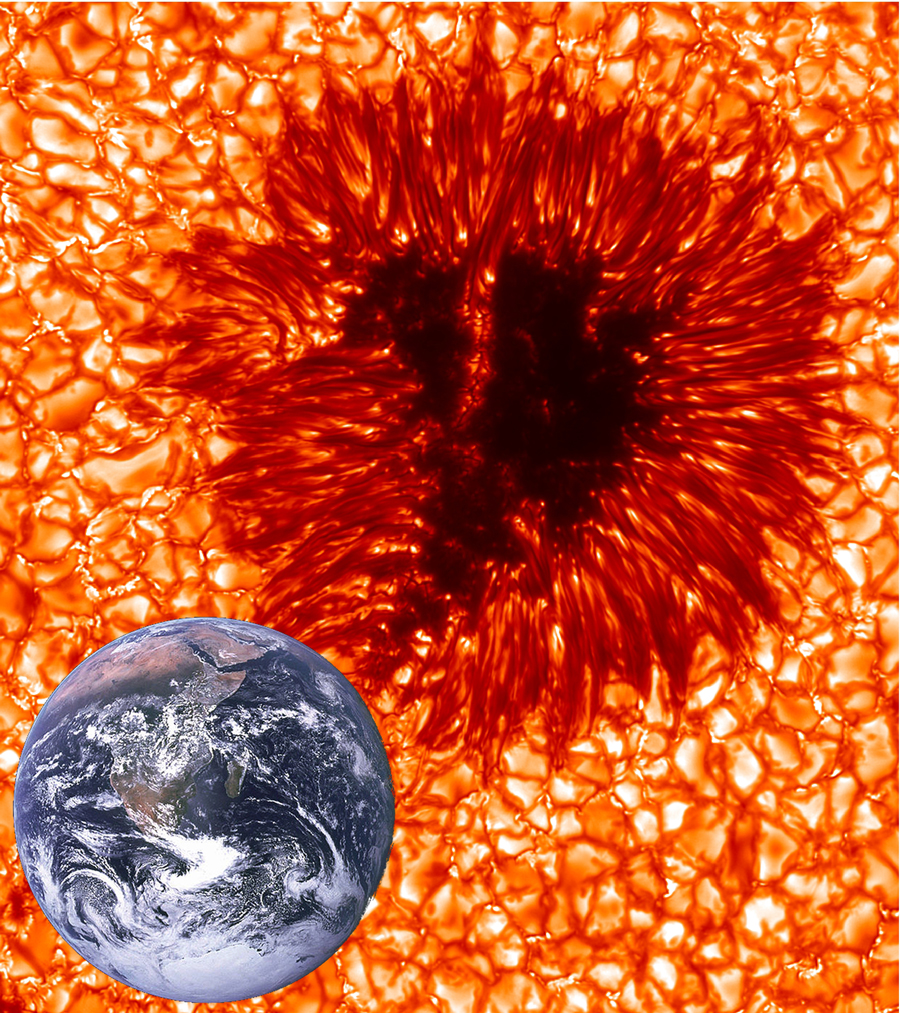

Spots on the sun

Sunspots are temporary patches on the surface of the sun that are caused by intense magnetic activity. These structures sometimes erupt into energetic solar storms that send streams of charged particles into space.

Since powerful charged particles from solar storms can occasionally wreak havoc on Earth's magnetic field by knocking out power grids or disrupting satellites in orbit, a calmer solar cycle could have its advantages.

Astronomers study mysterious sunspots because their number and frequency act as indicators of the sun's activity, which ebbs and flows in an 11-year cycle. Typically, a cycle takes roughly 5.5 years to move from a solar minimum, when there are few sunspots, to the solar maximum, during which sunspot activity is amplified.

Currently, the sun is in the midst of the period designated as Cycle 24 and is ramping up toward the cycle's period of maximum activity. However, the recent findings indicate that the activity in the next 11-year solar cycle, Cycle 25, could be greatly reduced. In fact, some scientists are questioning whether this drop in activity could lead to a second Maunder Minimum, which was a 70-year period from 1645 to 1715 when the sun showed virtually no sunspots. [Video: Rivers of Fire Inflame Sunspots]

Hill is the lead author of one of the studies that used data from the Global Oscillation Network Group to look at characteristics of the solar interior. (The group includes six observing stations around the world.) The astronomers examined an east-west zonal wind flow inside the sun, called torsional oscillation. The latitude of this jet stream matches the new sunspot formation in each cycle, and models successfully predicted the late onset of the current Cycle 24.

"We expected to see the start of the zonal flow for Cycle 25 by now, but we see no sign of it," Hill said. "The flow for Cycle 25 should have appeared in 2008 or 2009. This leads us to believe that the next cycle will be very much delayed, with a minimum longer than the one we just went through."

Hill estimated that the start of Cycle 25 could be delayed to 2021 or 2022 and will be very weak, if it even happens at all.

The sun's magnetic field

In the second study, researchers tracked a long-term weakening trend in the strength of sunspots, and predict that by the next solar cycle, magnetic fields erupting on the sun will be so weak that few, if any, sunspots will be formed.

With more than 13 years of sunspot data collected at the McMath-Pierce Telescope at Kitt Peak in Arizona, Matt Penn and William Livingston observed that the average magnetic field strength declined significantly during Cycle 23 and now into Cycle 24. Consequently, sunspot temperatures have risen, they observed.

If the trend continues, the sun's magnetic field strength will drop below a certain threshold and sunspots will largely disappear; the field no longer will be strong enough to overcome such convective forces on the solar surface.

In a separate study, Richard Altrock, manager of the Air Force's coronal research program at NSO's facility in New Mexico, examined the sun's corona and observed a slowdown of the magnetic activity's usual "rush to the poles."

"A key thing to understand is that those wonderful, delicate coronal features are actually powerful, robust magnetic structures rooted in the interior of the sun," Altrock said. "Changes we see in the corona reflect changes deep inside the sun."

Altrock sifted through 40 years of observations from NSO's 16-inch (40 centimeters) coronagraphic telescope.

New solar activity typically emerges at a latitude of about 70 degrees at the start of the solar cycle, then moves toward the equator. The new magnetic field simultaneously pushes remnants of the past cycle as far as 85 degrees toward the poles. The current cycle, however, is showing some different behavior.

"Cycle 24 started out late and slow and may not be strong enough to create a rush to the poles, indicating we'll see a very weak solar maximum in 2013, if at all," Altrock said. "If the rush to the poles fails to complete, this creates a tremendous dilemma for the theorists, as it would mean that Cycle 23's magnetic field will not completely disappear from the polar regions. … No one knows what the sun will do in that case."

If the models prove accurate and the trends continue, the implications could be far-reaching.

"If we are right, this could be the last solar maximum we'll see for a few decades," Hill said. "That would affect everything from space exploration to Earth's climate."

You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.