If you look to the east at night with a telescope this week, you may see a bright cluster of stars with a powerful name and a discovery story that dates back to the 18th century.

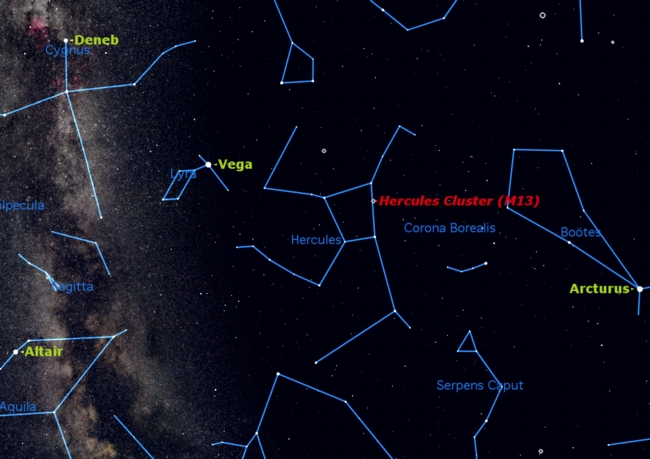

The cluster is an especially beautiful Messier object known as the great globular cluster M13, in the constellation Hercules, which stands high in the eastern sky at dusk this week. Because of its location, the cluster is sometimes known as the Globular Cluster of Hercules. The sky map available here shows where the cluster appears in relation to other constellations.

Famous star clusters and glowing cosmic nebulas are often denoted by names that begin with the letter M, such as M42 (the Orion nebula) and M31 (the Andromeda galaxy). These objects are part of the storied Messier catalogue, created by 18th century comet observer Charles Messier (1730-1817).

Find the Keystone

To locate Messier 13, look toward the four stars known as the "Keystone," which supposedly forms the body of Hercules. A keystone is the stone atop an arch, and is narrower at one end. The keystone of Hercules is composed of the stars Eta, Pi, Epsilon, and Zeta Herculis. It's an asterism, which is defined as a distinctive grouping of stars forming part of the recognized constellation outlines, or lying within its boundaries.

Ranging in size from sprawling naked-eye figures to minute stellar settings, asterisms are found in every quarter of the sky and at all seasons of the year. The larger asterisms – ones like the Big Dipperin Ursa Major and the Great Square of Pegasus– are often better known than their host constellations.

It's between the two western stars of the keystone that we can find the Great Globular Cluster of Hercules. It's about a third of the way along a line drawn from the stars Eta to Zeta.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Actually, it was not Messier, but Edmund Halley (of comet fame), who first mentioned this cluster in 1715, having discovered it the previous year: "This is but a little Patch," he wrote, "but it shows itself to the naked Eye, when the Sky is serene and the Moon absent."

Located at a distance of about 25,000 light-years, the Globular Cluster of Hercules has been estimated to be a ball of tens of thousands of stars roughly 160 light-years in diameter. Globular clusters are masses of stars that typically lie on the outskirts of our galaxy.

False comets

Messier was deeply interested in discovering comets but he was plagued by the same trouble that besets all comet hunters. He kept finding "comets" that were not comets at all but only star clusters and nebulae. His hopes were dashed so often that for his own convenience he kept a list of these deceiving objects, which he published in a catalogue.

Messier first saw the Hercules cluster in June 1764, and described it as a "round and brilliant nebula with a brighter center, which I am sure contains no stars."

Today, if you use good binoculars and look toward that spot in the sky where M13 is, you likely will see a similar view: a roundish glow or patch of light.

Moving up to a telescope, the view dramatically improves. With a 4 to 6-inch telescope, the "patch" starts to become resolved into hundreds of tiny pinpoints of light. In larger instruments, Messier 13 is transformed into a spectacular celestial chrysanthemum. [New Tips to See Ancient Star Clusters With Telescopes]

In his Celestial Handbook, Robert Burnham describes the view of the cluster in a 12-inch or larger telescope as "an incredibly wonderful sight; the vast swarm of thousands of glittering stars, when seen for the first time or the hundredth, is an absolutely amazing spectacle."

An oldie but goodie

For those who regularly attend the annual Stellafane convention, which is held just outside of Springfield, Vt. (which in 2011 takes place July 28-31), the Great Hercules Cluster is the object that the 12-inch Porter turret telescope on Breezy Hill is directed toward most often.

Many years ago, the legendary deep sky observer, Walter Scott Houston (1912-1993) – known to one and all as "Scotty" – noticed a long line of people patiently waiting their turn to get a view through the eyepiece.

"What are you folks looking at?" he asked as he poked his head through the observatory door. From out of the darkness, came the response: M13. "M13?" replied Scotty, with a tinge of incredulity. "So many people have looked at it, you would think it'd be worn out by now!"

Stellar nuisances

Many of the objects listed in Messier's catalogue have turned out to be beautiful star clusters like that in Hercules. Others are great clouds of nebulosity, while still others are galaxies similar to our own.

Yet, there is absolutely no reason to believe that Messier had the slightest interest in these objects. They were all merely a nuisance to him.

The 13 comets that Messier discovered and of which he was so proud of are long gone and forgotten now. But his catalogue, the by-product of his main work, has turned out to be amazingly useful to astronomers. His catalogue numbers have been retained and are the principal reason Messier is still remembered today.

Messier's original list contained 45 celestial objects and was published in 1774. By 1781, the list had grown to 103. Historians have since added seven more objects that were seen, but never catalogued by Messier.

Single-minded zeal

It has been written by many that Messier had consummate skill in making astronomical observations, even though by contemporary standards the telescopes he utilized were inefficient and crude (that fact is made obvious by his description of the Great Cluster in Hercules). Nonetheless, he was highly ambitious and always sought recognition of his observing skills and comet discoveries.

One oft-repeated anecdote demonstrates Messier's single-minded and zealous pursuit for finding comets.

On the occasion that a rival, Jacques Leibax Montaigne (1716-1785), discovered a brand new comet, Messier was holding watch at his wife's deathbed.

When a friend later offered condolences for his loss, Messier – thinking only of the comet – answered, "I had discovered twelve, alas, to be robbed of the thirteenth by that Montaigne!" His eyes then began to fill with tears. There was a long, awkward moment and then, realizing his friend was actually commenting not about comets but about his wife, Messier quickly added "Ah! The poor woman."

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.