New Flavors of Super-Dense Stars Found, Study Suggests

Researchers might have detected different breeds of dense stars called neutron stars, each created by different kinds of exploding stars.

Neutron stars are stellar corpses left over from supernovas, huge star explosions that crush protons together with electrons to form neutrons. This neutron star matter is the densest known material, with a sugar cube-size piece weighing as much as a mountain at about 100 million tons. The mass of a single neutron star exceeds that of the entire sun, but squeezed into a ball smaller in diameter than the city of London.

Two kinds of supernovas are thought to produce the overwhelming majority of neutron stars in the universe. One type is the iron-core-collapse supernova, which forms when a massive star becomes too laden down with iron to sustain its nuclear fires. Without this energy pushing matter outward, the star's core quickly collapses on itself. The other type is the electron-capture supernova, where atomic nuclei in a star's core glom onto electrons and become heavier and slower, thus decreasing outward pressure and leading to rapid collapse. In both cases, matter rushing inward violently rebounds off the core, leading to a supernova explosion that can briefly outshine entire galaxies.

"Theoreticians have speculated before about the possible existence of different types of neutron stars, but there has never been any clear observational evidence that there is really more than one type," said study co-author Malcolm Coe, an astrophysicist at the University of Southampton in England. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

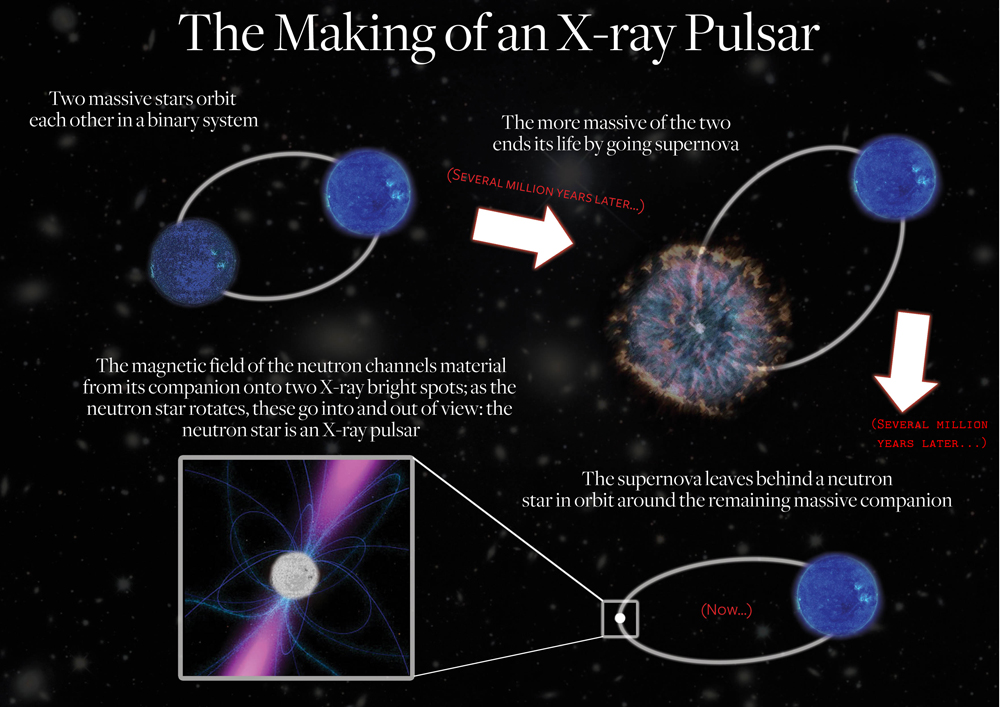

Now researchers suggest they have detected these distinct breeds of neutron stars by analyzing nearly 100 high-mass X-ray binaries — double star systems in which a fast-spinning neutron star orbits a massive young companion. The neutron stars in these binaries periodically siphon off material from their partners, which can slam into neutron stars at near-light-speed, generating pulses of X-rays. By timing these pulses, astronomers can accurately measure how quickly these neutron stars whirl.

The investigators detected two distinct classes of X-ray pulsars this way with the Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer and ground-based telescopes in South Africa and Chile. One group of neutron stars typically completed a spin once every 10 seconds, and the other once every 5 minutes. In addition, some of the slower-spinning stars seemed to have more eccentric, oval-shaped orbits with their companion stars than the faster-spinning stars did.

"Our results suggest strongly for the first time that not all neutron stars are the same," Coe told SPACE.com. "There appear to be some subtle but important differences."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers suggest these different kinds of neutron stars were created by different classes of supernovas, although it's uncertain which supernova type created each breed of neutron star. Perhaps the slower-spinning neutron stars with a more eccentric orbit were created by iron-core-collapse supernovas, and the faster-spinning neutron stars with a less eccentric orbit were created by electron-capture supernovas — iron-core-collapse supernovas should in theory impart more of a kick to any resultant neutron star, for a more eccentric orbit.

Confirming this idea by measuring the eccentricity of the orbits of all these neutron stars is going to be tricky — "we only see these objects intermittently," Coe said. "It may take a while to make the next step."

Coe and his colleagues Christian Knigge and Philipp Podsiadlowski detailed their findings online Nov. 9 in the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us