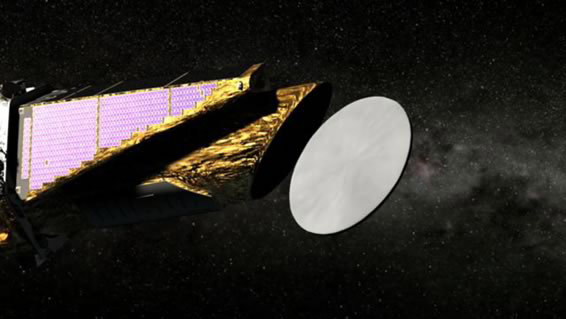

Planet-Hunting Telescope Needs Four More Years to Complete Mission, Scientists Say

MOFFETT FIELD, Calif. — The Kepler space telescope will be unable to achieve all of its mission goals unless NASA doubles the mission's length, say scientists working with the prolific planet-hunting instrument.

Funding for Kepler is slated to run out in November 2012. The Kepler team wants to keep the telescope running through 2016 or so.

"The task at hand is to spread this news to our colleagues so that they will recognize that if Kepler doesn't get an extended mission, exoplanet science is going to suffer a setback of decades," Natalie Batalha, deputy leader of the Kepler science team here at NASA's Ames Research Center, said Monday (Dec. 5).

In its 2 1/2 years of operation to date, the telescope has found about 30 confirmed alien planets and has discovered nearly 2,300 other candidates, most of which will likely be confirmed eventually, researchers say.

And this week, the Kepler team announced its first confirmation of a roughly Earth-like planet capable of sustaining liquid water and, therefore, perhaps even life as we know it.

"Kepler has made a very significant impact on exoplanet science," Batalha said in a talk during the First Kepler Science Conference at Ames.

Still, the Kepler mission has been slowed by unexpectedly high variations in the data being acquired by the space telescope. Scientists say the extra time would allow them to overcome these variations and detect more small, rocky planets, whose signals can be swamped by noisy data.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team is planning to submit a proposal in February.

Hunting for alien worlds

The $600 million Kepler spacecraft launched in March 2009. Its mission is to search for Earth-size planets in or near their parent stars' "habitable zone" — a region around the stars that could allow water to exist in liquid form.

The Kepler mission's overall goal is to help scientists determine just how common such planets may be throughout our galaxy. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

The telescope finds alien worldsby what's called the transit method. It looks for the tiny dips in a star's light that occur when a planet passes in front of it. Kepler generally needs to see three such passes, or transits, to flag a potential exoplanet.

Kepler has been very productive. On Monday, mission scientists announced the discovery of 1,094 new exoplanet candidates, bringing the instrument's total tally to 2,326 potential alien worlds in its first 16 months of operation (through September 2010).

These finds can graduate from candidates to bona fide planets after follow-up observations, which are usually performed by large ground-based instruments. One of these confirmed planets is just 2.4 times bigger than Earth and orbits in the habitable zone of its sun-like star, the Kepler team announced this week.

While only about 30 of Kepler's candidate planets have been confirmed so far, mission researchers have predicted that at least 80 percent of them will eventually make the cut.

Extending the mission?

Mission scientists don't want the lights to go out on Kepler next year. They're working on a proposal to extend the telescope's mission for four years beyond November 2012.

Like most federal agencies, NASA faces an uncertain budget future, but researchers contend that a Kepler extension is unlikely to break the bank. It currently costs about $20 million per year to operate the telescope and analyze its data, they said.

Giving Kepler four more years would let the telescope extend its observational reach to planets that orbit far from their host stars, researchers said. These worlds take longer to complete a circuit, so their transits aren't as frequent.

An extension also would let Kepler scientists deal with an issue they didn't anticipate when they were planning its mission: relatively noisy data.

Noisy stars

The noise, or fluctuations, in Kepler's measurements of stars' brightness is about 50 percent greater than mission scientists had predicted, primarily because the stars are twice as variable as had been expected, researchers said.

The scientists are not quite sure why the stars are so changeable.

"It's a mystery," Kepler analysis lead Jon Jenkins, of Ames and the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute, told SPACE.com.

The surprisingly noisy data makes it tough for Kepler to pick out relatively small planets after just three transits. As a result, Kepler is unlikely to achieve its full mission goals in its allotted 3 1/2 years. That's just not enough time to determine how commonly Earth-size planets occur in the habitable zones of their parent stars, researchers said.

"We can recover that by getting more transits," said Doug Caldwell, Kepler instrument scientist at the SETI Institute.

A mission length of eight years should give Kepler enough time, Caldwell added.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.