Found! 2 Earth-Size Alien Planets, the Smallest Exoplanets Yet

This story was updated at 1:54 p.m. ET.

Two planets orbiting a star 950 light-years from Earth are the smallest, most Earth-size alien worlds known, astronomers announced today (Dec. 20). One of the planets is actually smaller than Earth, scientists say.

These planets, while roughly the size of our planet Earth, are circling very close to their star, giving them fiery temperatures that are most likely too hot to support life, researchers said. The discovery, however, brings scientists one step closer to finding a true twin of Earth that may be habitable.

"We've crossed a threshold: For the first time, we've been able to detect planets smaller than the Earth around another star," lead researcher François Fressin of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., told SPACE.com. "We proved that Earth-size planets exist around other stars like the sun, and most importantly, we proved that humanity is able to detect them. It's the beginning of an era."

To discover the new planets, Fressin and his colleagues used NASA's Kepler space telescope, which noticed the tiny dips in the parent star's brightness when the planets passed in front of it, blocking some of its light (this is called the transit method). The researchers then used ground-based observatories to confirm that the planets actually exist by measuring minute wobbles in the star's position caused by gravitational tugs from its planets.

"These two new planets are the first genuinely Earth-sized worlds that have been found orbiting a sunlike star," University of California, Santa Cruz astronomer Greg Laughlin, who was not involved in the new study, said in an email to SPACE.com. "For the past two decades, it has been clear that astronomers would eventually reach this goal, and so it's fantastic to learn that the detection has now been achieved." [Gallery: Smallest Alien Planets Ever Seen]

Chances for life

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The two Earth-size planets are among five alien worlds orbiting a star called Kepler-20 that is of the same class (G-type) as our sun, and is slightly cooler.

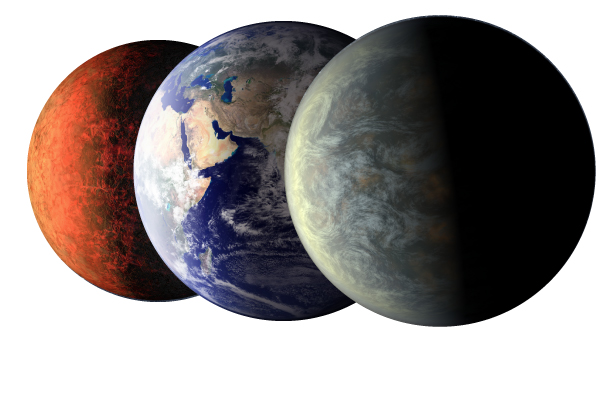

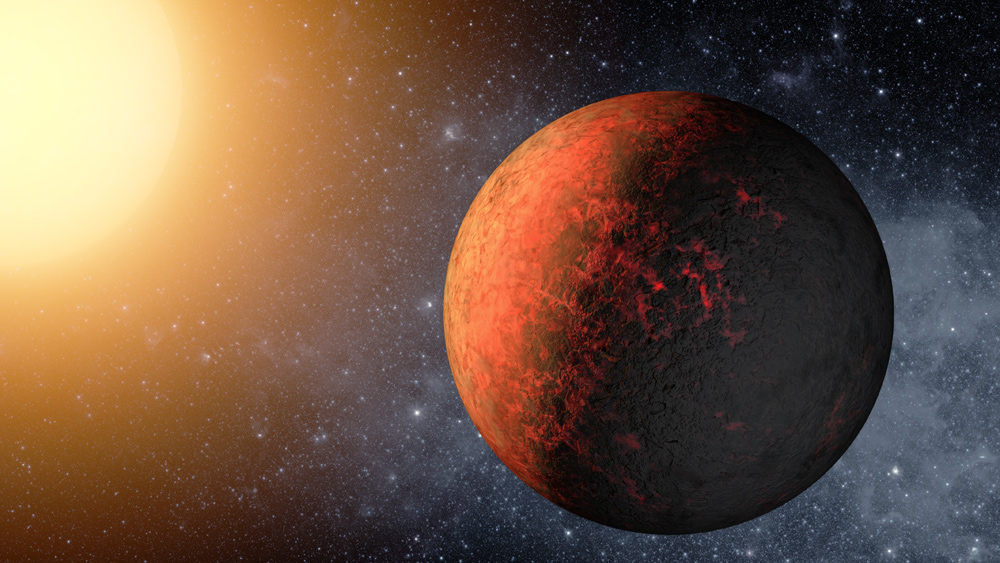

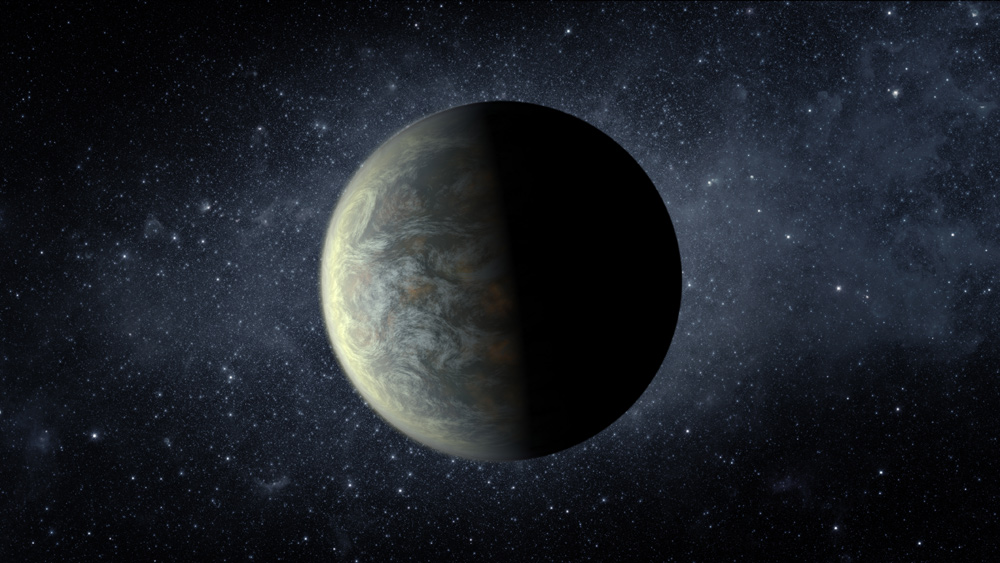

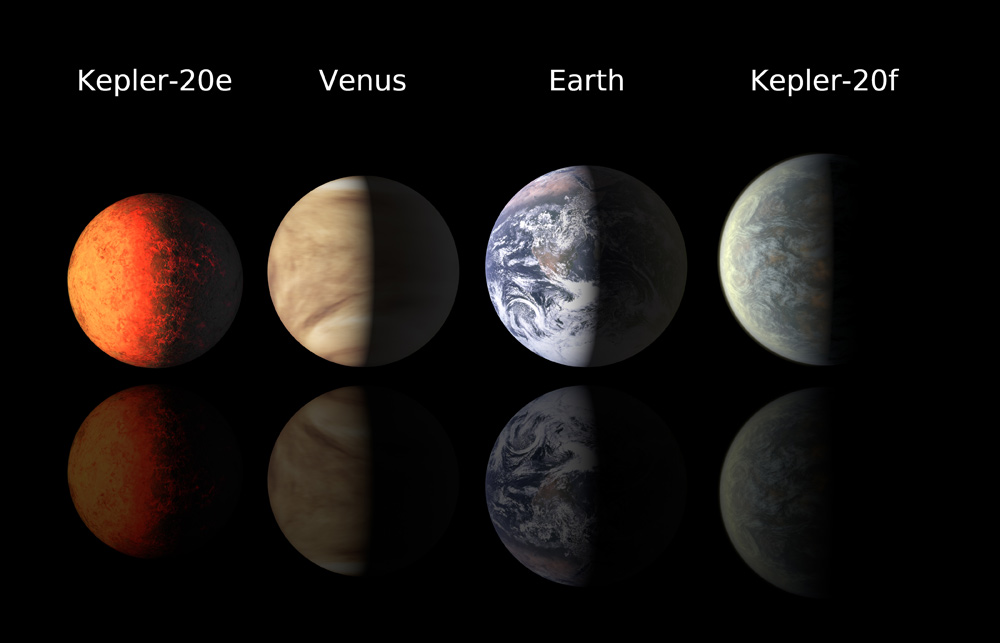

Two of the star system's planets, Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, are 0.87 times and 1.03 times the width of Earth, respectively, making them the smallest exoplanets yet known. They also appear to be rocky, and have masses less than 1.7 and 3 times Earth's mass, respectively. Scientists think that they are composed mainly of silicates and iron, much like the Earth, though they lack our planet's atmsophere.

Kepler-20e makes a circle around its star once every 6.1 days at a distance of 4.7 million miles (7.6 million kilometers) — almost 20 times closer than Earth, which orbits the sun at around 93 million miles (150 million km).

The planet's sibling, Kepler-20f, makes a full orbit every 19.6 days, at a distance of 10.3 million miles (16.6 million km). Both planets circle closer to their star than Mercury does to the sun. [Infographic: Earth-Size Alien Planets Explained]

These snuggly orbits around their star give the newfound planets steamy temperatures of about 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit (760 degrees Celsius) and 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius) — way too warm to support liquid water, and probably life, researchers said.

Fressin said the chance of life on either of these planets is "negligible," though the researchers can't exclude the possibility that they used to be habitable in the past, when they might have been farther from their star. There is also a slim chance that there are habitable regions on the planets in spots between their day and night sides (the planets orbit with one half constantly facing their star and the other half always in dark). But astronomers aren't holding out hope.

"The chances of liquid water and life as we know it on Kepler-20e and f are zero," Laughlin said.

Flip-flopped planets

The planetary system around Kepler-20 is an unusual one.

For one thing, scientists say the rocky planets can't have formed in their current locations.

"There's not enough rocky material that close to the host star to form five planets," Fressin said. "They didn't form here; they probably formed farther from their star and migrated in."

Furthermore, the five planets are in an odd order, with the rocky worlds alternating with their gaseous, Neptune-size siblings. That's quite different from most solar systems, including our own, which keeps the rocky terrestrial worlds in close to the sun, with the gas giants farther out.

"The architecture of that solar system is crazy," science team member David Charbonneau of Harvard University said during a Tuesday telecon announcing the finding. "This is the first time that we've seen anything like this."

Scientists will likely have to revise their theories of how planets form to fully understand the Kepler-20 system.

"How did that form?" Fressin said. "I think it's a puzzle the theorists will have to try to explain."

The star's other planets are called Kepler-20b, 20c, and 20d. Their diameters are 15,000 miles (24,000 km), 24,600 miles (40,000 km), and 22,000 miles (35,000 km), respectively, and they orbit Kepler-20 once every 3.7, 10.9, and 77.6 days.

The largest of these, Kepler-20d, weighs a little under 20 times Earth's mass, while Kepler-20c is 16.1 times as heavy as Earth, and Kepler-20b is 8.7 times our planet's mass.

Evolving effort

Scientists say finding the smallest exoplanets yet represents a significant milestone in the fast-evolving effort to learn about planets beyond the solar system.

The first alien planet was discovered in 1996, and the first planet found through the transit method came just 11 years ago. Both of those planets were roughly the size of Jupiter.

"I think we're living in special times," Fressin said. "This was unfeasible 10 years ago, and just with the quality of detectors and the quality of the treatment is it possible now."

The total tally of known alien planets is above 700. Kepler alone has discovered 28 definite alien planets, and 2,326 planet candidates, since its launch in March 2009.

Earlier this month, the Kepler team announced another landmark find, the first planet known to occupy the habitable zone around its star where liquid water, and perhaps life, could exist.

That planet, called Kepler-22b, is about 2.4 times as wide as Earth.

The dream now is for astronomers to combine the two discoveries and find an Earth-size planet that's also orbiting its star in an Earth-like orbit that puts it in the habitable zone.

"The holy grail of the search for other worlds is to find an Earth analogue, a true Earth twin," Fressin said. "We just need to have these two pieces of the puzzle together."

While the newfound planets orbit with periods of 6.1 and 19.6 days, Fressin estimated the habitable zone around Kepler-20 begins at orbits that take roughly 100 days to make a circuit.

Astronomers think it's only a matter of time before they finally find one that's just right.

"These discoveries are a great technological step forward — to detect small planets, in size like Earth — but these planets are very hot and not in the habitable zone around their star," astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics wrote in an email. Kaltenegger, who studies the habitability of exoplanets, was not involved in the new study. "If we can already find these small planets with radii around Earth's now, some future ones could be in the habitable zone of their stars and THOSE future ones would be great targets to look for liquid water and signatures for life."

A paper detailing the discovery was published online in the journal Nature Dec. 20.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.