Sun's 2013 Solar Storm Peak Expected to Hit Century Low

The sun's peak of solar activity this year will likely be the quietest seen in at least 100 years, say NASA scientists who watch Earth's closest star daily.

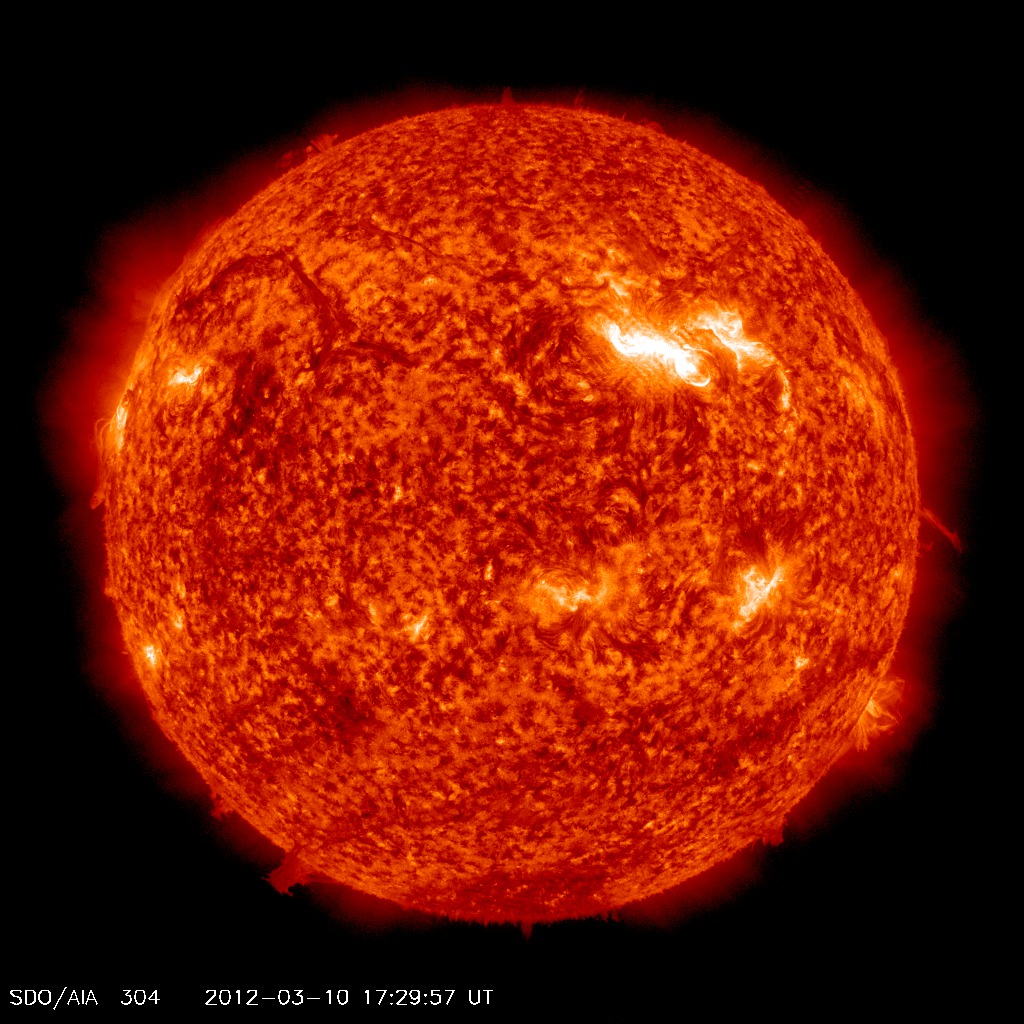

Sunspot numbers are low, researchers said, even as the sun reaches the peak of its 11-year activity cycle. Also, radio waves that are known to indicate high solar activity have been very subdued.

"It's likely to be the lowest solar maximum, as measured by sunspot 'number,' in more than a century," wrote Joe Gurman, a project scientist for NASA's sun-observing mission Stereo, or Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory. The current sun weather cycle is known as Solar Cycle 24.

Quiet as the sun may be, scientists still have a vested interest in watching it. A rogue flare could damage electrical grids or knock out communications satellites, as has happened many times before.

Though solar science is still in its infancy, it has advanced greatly even from the time solar activity knocked out much of Quebec's electrical grid in 1989, Gurman pointed out. [Worst Solar Storms in History]

"The interconnectedness of power grids has grown tremendously since the Hydro Québec issue," he wrote.

"Compared to the frequency of widespread power outages due to trees falling on above-ground power lines during snowstorms or hurricane-force winds from storms such as the recent [Hurricane] Sandy, it's a very low order of probability event."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Killer flares 'a physical impossibility'

Galileo Galilei was among the first to sight sunspots when he turned his telescope to the sun in 1610. Reliable records of sunspots date back to about 1849, when the Zurich Observatory began daily observations, according to NASA.

Sunspots appear as dark blemishes on the sun, generally in clusters above and below the equator. Scientists now know these spots form due to the interplay between the sun's plasma (on the surface) and its magnetic field.

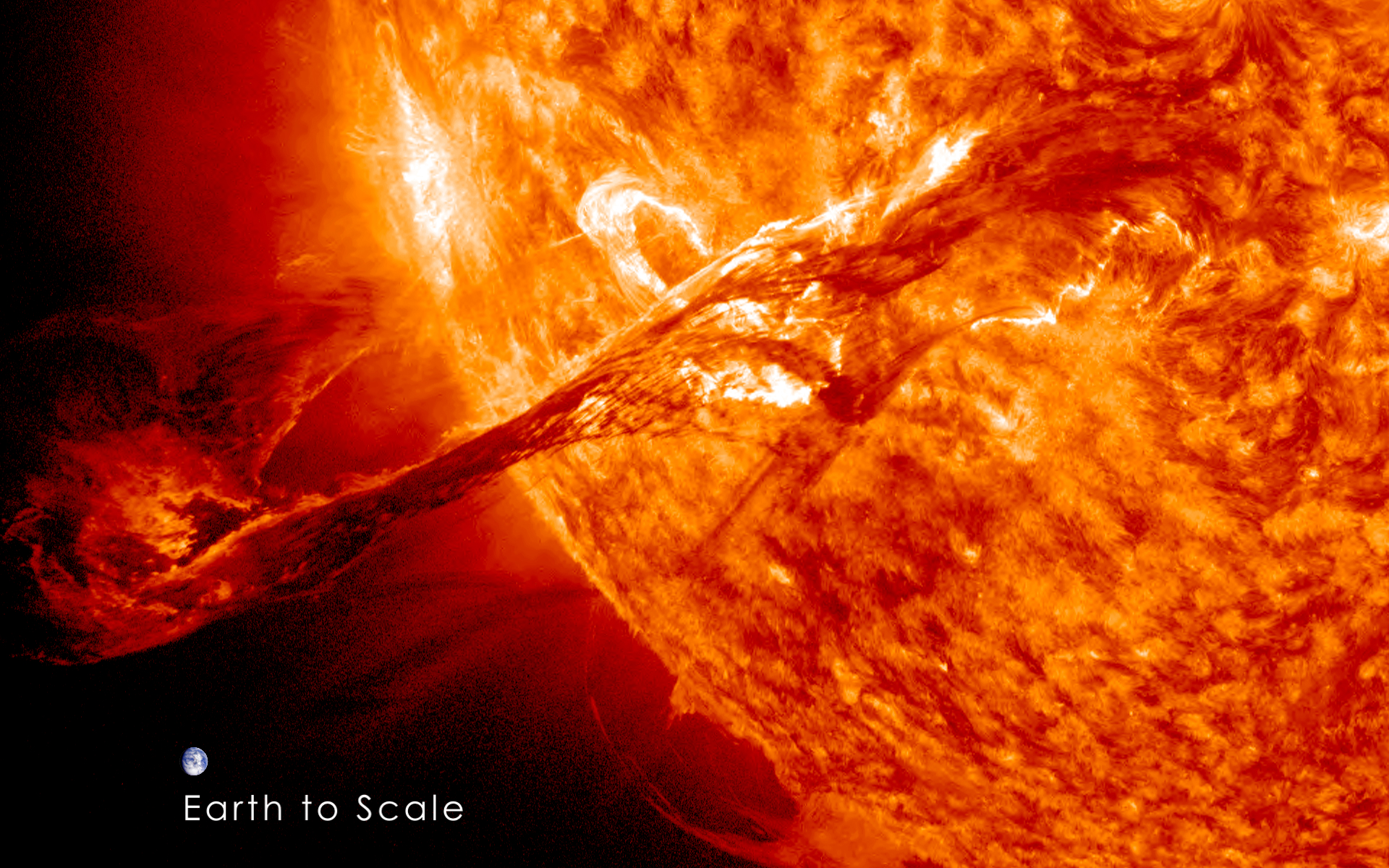

Under some circumstances, the twisting magnetic fields near sunspots cause huge explosions such as solar flares, and plasma-rich coronal mass ejections often associated with the flares. These send charged particles out from the sun, and occasionally toward Earth.

The strongest category of outburst, called an X-class solar flare, can cause havoc if it reaches Earth. The electrical charge can short out communications satellites or power grids. Medium-class M-type solar flares can supercharge Earth's northern lights displays, while weaker C-class flares and below can have relatively little effect, NASA has said.

It is impossible for the sun to produce "killer" solar flares that were made popular by 2012 doomsday predictions, NASA's C. Alex Young told SPACE.com in an email.

"On Earth we are completely protected from the direct effects of solar activity. The atmosphere shields us from the electromagnetic radiation from solar flares and the particles in a particle storm," wrote Young, a solar astrophysicist with NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. [Doomsday Myths Debunked by NASA: Countdown]

"[Killer flares] would not happen. The sun cannot produce flares (or CMEs) with enough energy to do this. It is a physical impossibility. It would take the entire energy of the sun, like a supernova. The sun will not become a supernova."

Solar watching is a young science, but in recent decades, NASA has been working to improve the ability to predict and track solar flares and CMEs. The primary way is through using satellites to peer at the sun.

The United States' official "space weather" forecaster is the Space Weather Prediction Center, a service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Several NASA satellites feed the center data to assist with its predictions.

According to NASA's William Pesnell, NASA's satellites work together like this:

- The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) can watch for CMEs from the moment they erupt from the sun.

- The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) watches the charged particles, or plasma, on their journey toward Earth, making it easier to determine if they will hit the planet.

- If the plasma is Earth-bound, the two Stereo satellitesorbiting the planet then observe the plasma and predict where it could hit.

"The Earth is a very small target in a big solar system, and the models that try to track the CME through the solar system are still being developed," added Pesnell, the project scientist for SDO, in an e-mail to SPACE.com.

"Our biggest advances," he added, "have been in models of the sun's magnetic field and using data in those models to explain the current sun. ... Our models try to explain the 11-year behavior of the solar cycle as the magnetic field moves around inside the sun, and then erupts through the surface to become sunspots."

NASA also plans to launch the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) mission in April 2013. When the satellite is ready, it will watch how energy and plasma move from the sun's surface to its corona or atmosphere, Pesnell said.

"That means we will have good overlap to combine the different measurements [with SDO] and better understand the magnetic field of the sun."

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.