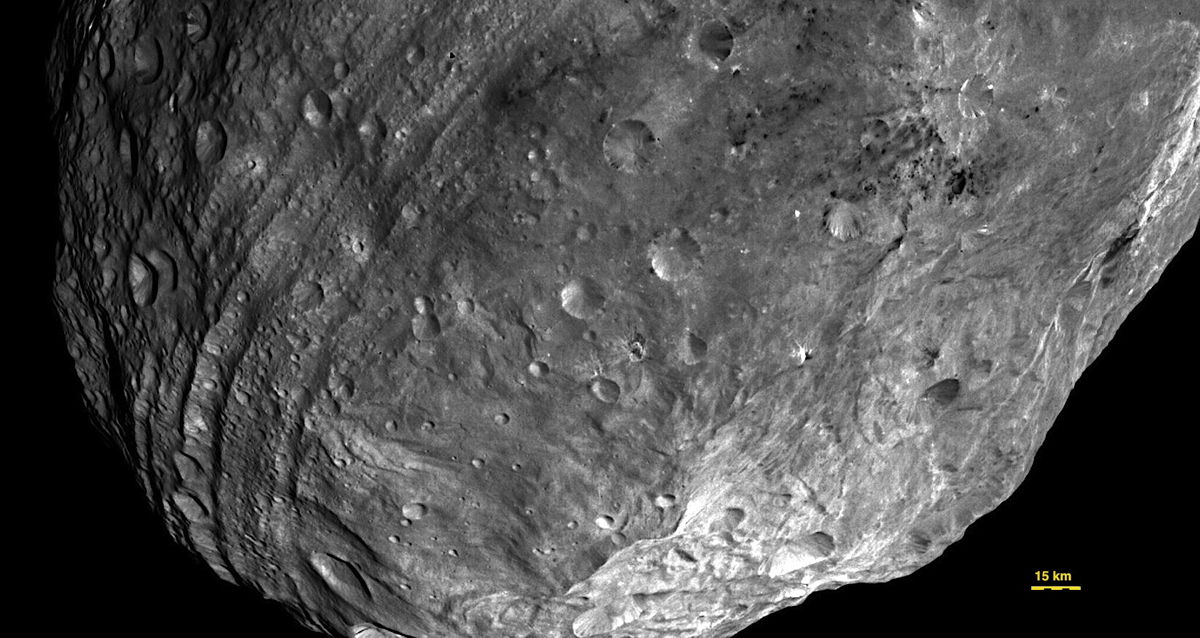

Earth's Moon and Huge Asteroid Vesta Share Violent History

The same population of space rocks that battered Earth's moon during the early days of the solar system also slammed the huge asteroid Vesta, scientists say.

While the cosmic bombardment – which occurred when Jupiter and Saturn shifted orbits – has been known for a while, this is the first time scientists found evidence of it on Vesta, one of the biggest asteroids in the solar system.

NASA Apollo astronauts collected evidence of the bombardment on the moon during the lunar landing missions of the 1960s and 1970s. On Earth, erosion washed away most of the evidence of the violent chapter during the solar system's formation, researchers said.

"We wanted to study the evolution of the solar system. That was the main topic. So we tried to tackle that with a different scenario approach," said Simone Marchi, who is with the NASA Lunar Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., told SPACE.com. [Photos of Asteroid Vesta by NASA's Dawn Probe]

But it was a surprise to find that the moon and Vesta share the same bombardment history, NASA officials said in a statement. The discovery found that the same population of rocks that etched craters on the moon also affected the asteroid belt's history.

The research, led by Marchi, appears in Sunday's (March 24) issue of the journal Nature Geoscience.

Heavy cosmic artillery

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At 319 miles (523 kilometers), Vesta is big enough for an amateur using binocularsto see it. It is so large that it is considered by some scientists as a "protoplanet," or large body that is similar in size to the genesis of the planets in the solar system today.When the solar system was still forming, some planets experienced a sort of dynamic instability as they orbited around the young sun. It was at this period of time that Jupiter and Saturn began moving in their orbits, according to the Nice model of planet formation.

The planets' movements — which took place in only about a million years or so — spurred what is now known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. This coincides with the time that life began to arise on Earth roughly 3.9 billion years ago. Icy and rocky bodies careened into the inner solar system, pummelling the moon, the Earth and other large objects.

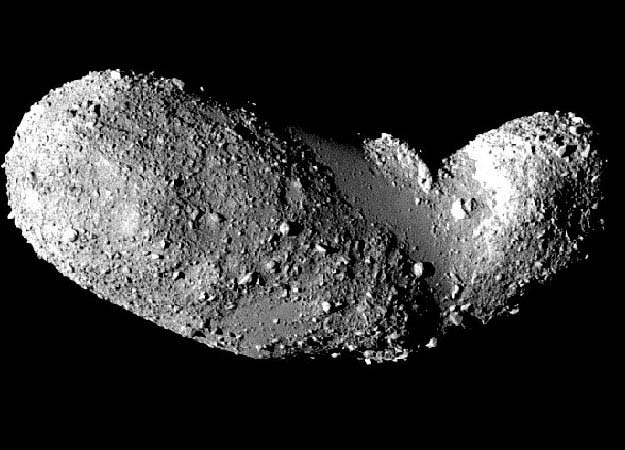

Asteroids ejected into high-speed planetary-crossing paths, by their nature, should only have a lifetime of a few tens of millions of years before crashing.

Scientists said it was unlikely that they all were ejected at once. Rather, they were moved in periods stretching over hundreds of millions of years as the planets moved.

The planets' movements carried some asteroids into the inner solar system. The planets also altered the orbits of other asteroids that, after their orbits coincided with other bodies, eventually were kicked out into new orbits veering toward the sun.

Melting rock

Simulations showed that the greatest bombardment on Vesta happened between 4.1 billion and 4.55 billion years ago, as the mass of the young asteroid belt was at its highest. However, only 0.2 percent of impacts was high enough to melt the underlying rock.

That proportion jumps to about 11 percent in the next epoch of Vesta's history, about 3.5 billion to 4.1 billion years ago. This occurred when asteroids began "resonating" with each other and the planets in their orbits, sending some objects careening into the solar system and crashing into Vesta. While these encounters were more rare, they took place at a much higher speed.

A typical asteroid collision on Vesta today occurs at just 3 miles (5 km) a second, which is not fast enough to produce rock melting. On the moon, by contrast, a collision is nearly four times as fast: 11 miles (18 km) a second — that's about 39,600 mph (63,730 km/h). This is because Vesta is orbiting in a swarm of rocks moving at similar speeds, while the moon is on its own and closer to the sun's gravity, researchers said.

A new interpretation of radiometric dating of Vesta's ancient asteroids, however, revealed small bodies smashing into the surface twice as quickly — at velocities exceeding 6 miles (10 km) a second. Craters from these smaller meteorites on Vesta's surface vanished long ago due to gradual erosion from newer impacts.

Because argon is lost during impacts if the "target is heated for a long enough time beyond a threshold temperature," the paper stated, there's enough argon loss on ancient Vesta meteorites to show that they were moving much faster 4 billion years ago than previously believed.

Even later in asteroid's development, about 1 billion to 2 billion years ago, two nearly cataclysmic collisions changed the nature of the Vesta's interior. Scientists, who performed that research separately from Marchi and his colleagues, said this could explain why the asteroid has a thicker crust than could be explained previously.

A suite of NASA scientists were involved in the new research, including some from the Marshall Space Flight Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The agency-funded Lunar and Planetary Institute also participated, along with institutions in California, Tennessee, Arizona, Italy and Germany.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebookand Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.