Mercury's Volcanic Facelift Belies Planet's True Age

Mercury is looking good for its age.

Even the oldest parts of the surface of the planet closest to the sun are only 4 billion to 4.1 billion years old, not 4.5 billion years old — the age at which the planet formed, a new study finds.

"If the oldest surface visible on Mercury is 4 billion or 4.1 billion years old, then that would imply that the first perhaps 500 million or 400 million years of the planet have been erased," said Simone Marchi, a NASA Lunar Science Institute planetary scientist based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. and lead author of the study. "They are gone. There is no record of the oldest surface of Mercury, and we expect that Mercury pretty much formed like the Earth or the moon around 4.5 billion years ago." [Amazing Mercury Photos by NASA Spacecraft (Gallery)]

Marchi's research suggests that widespread volcanic activity on Mercury during its early years as a planet is to blame for the artificially young surface.

One reason for this could be that when the solar system was pelted with asteroids early in its history, Mercury's thin crust was punctured by space rocks, Marchi said. The impacts may have caused increased volcanism on the planet, effectively resurfacing the entire planet a short time after Mercury formed.

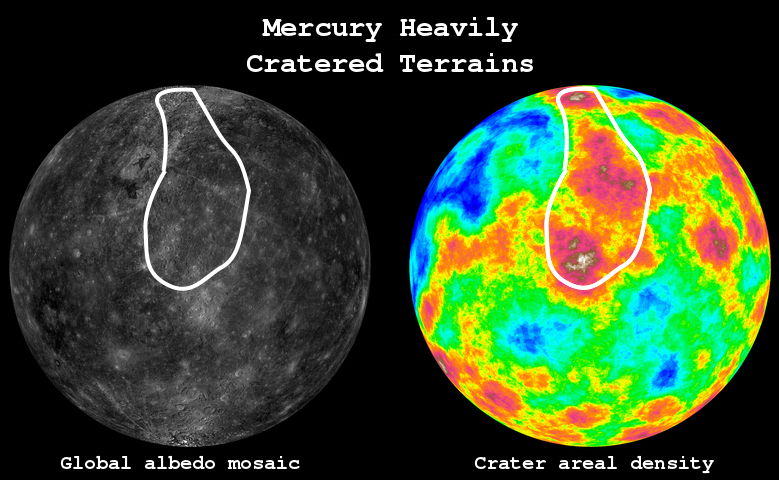

The team used a detailed map of Mercury by NASA's Messenger spacecraft in orbit around the planet to characterize the oldest regions on the planet's surface.

"Unfortunately we do not have samples from Mercury so we cannot really have precise age estimates of the terrains, but therefore the only thing we can possibly do is just look at the craters," Marchi told SPACE.com. "If there are more craters, this implies that the surface is older."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Older bits of the planet's face have had the most time to be impacted by errant space rocks, therefore making them the most cratered parts of a planetary body, Marchi said.

Scientists used this to their advantage. By characterizing the most pockmarked parts of the planet, Marchi and his team could compare the number of craters on any given part of Mercury to the number of craters on certain parts of the moon — a celestial object whose surface age is well documented.

"One of the major outcomes of the Apollo program was that those data allow us to make a connection between the number of craters that were observed on some lunar terrain and the true age of those terrains," Marchi said. "In that way, we calibrated the model and we know how many craters you have as a function of age of the terrain."

"That information we extrapolated out to Mercury using current astronomical models that predict what the impact flux from asteroids is on the moon and what the impact rate [is] on Mercury, so this model will tell us how we have to scale or extrapolate this lunar crater chronology to Mercury," Marchi added.

The model shows that for every one crater formed on a given surface on the moon per year, a similar surface on Mercury is dotted with three new craters in the same amount of time, Marchi said.

NASA's $446 million Messenger probe (which stands for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) was launched in 2004 and has been in orbit around Mercury since 2011.

The new research is detailed in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter and Google+. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.