Spica: The brightest star in the constellation Virgo

Location, history and cultural significance of Spica.

Spica is the 15th brightest star in the sky and the brightest in the Virgo constellation.

The star is also known as Alpha Virginis and is situated around 250 light-years from Earth. Spica is not a single star, but a binary system, meaning two stars orbit closely around one another, every four days. The stars lie approximately 11 million miles (less than 18 million kilometers) away from each other and appear as a single point of light in the sky.

The combined light from Spica's two stars is, on average, over 12,100 times more luminous than the light from our sun. Their diameters are estimated to be approximately 7.8 and 4 times the size of the sun's diameter.

Where is Spica and how can you see it?

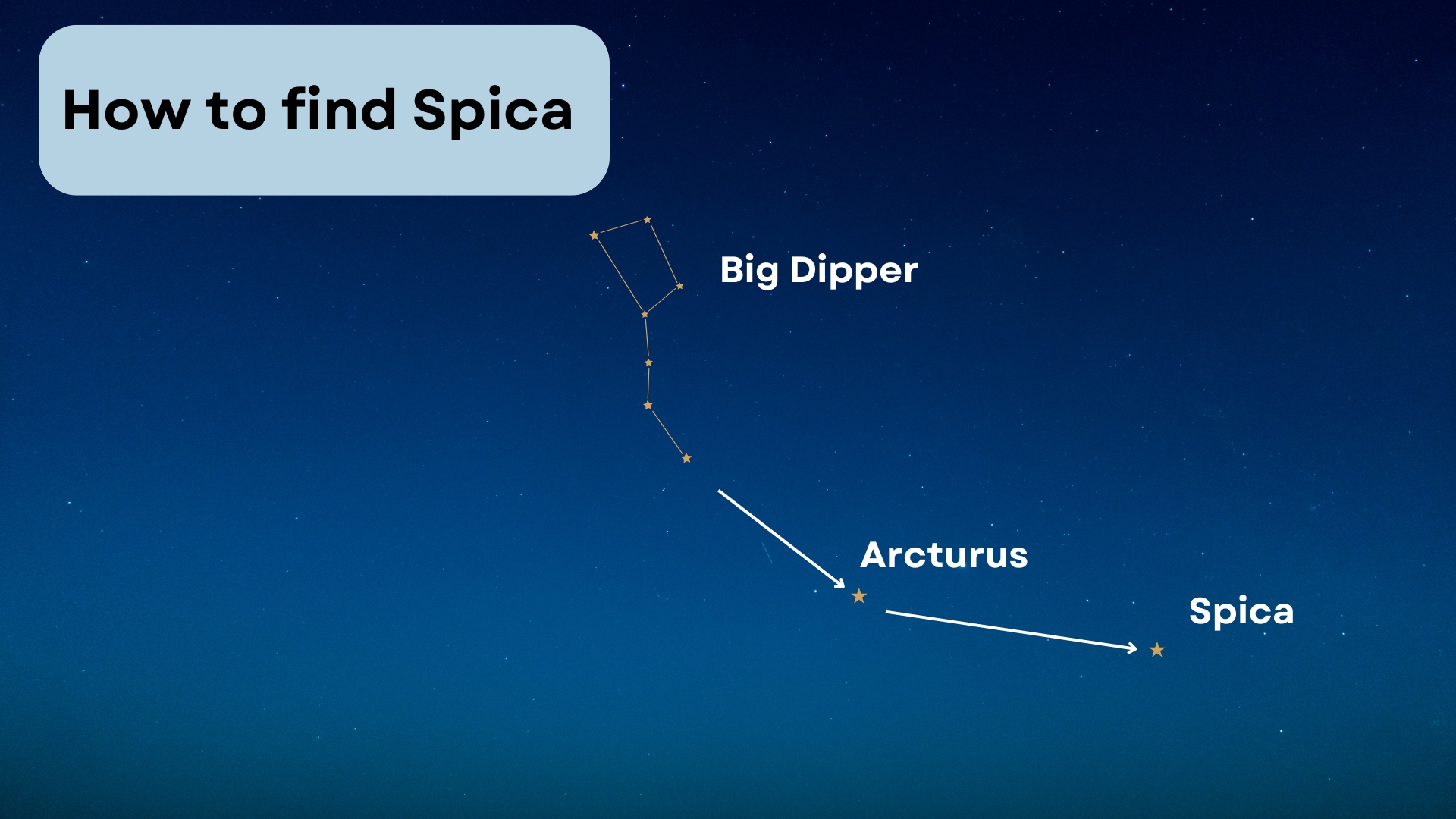

Spica is located in the constellation Virgo and is easy to find once you know where to look.

Spica rises in the southeast and appears highest in the sky late at night during spring for observers in the northern hemisphere. Its blue-white sparkle is unmistakable, especially on a clear evening

A helpful way to find Spica is using the 'arc' of the Big Dipper's handle. Follow the arc to the bright orange star Arcturus, then 'speed on' further to Spica.

Why is it called Spica?

The name Spica comes from the Latin word for 'ear' (of grain), according to Earth Sky. The common understanding is that Spica refers to an 'ear of wheat', a name that connects to the mythology of the constellation Virgo, often depicted as a maiden holding a sheaf of wheat.

Why is Spica important?

Throughout history, Spica has played an essential role in timekeeping and navigation.

Ancient Egyptians associated Spica with the goddess Isis was used to signal the beginning of the Nile flood season.

Spica has played an important role in navigation and timekeeping throughout history. In the 16th century, Portuguese sailors relied on Spica as a key reference point to calculate their longitude during sea voyages. Even today, astronomers utilize Spica as a calibration star to assess the brightness and color of other stars.

Spica is featured on Brazil's national flag, above the Portuguese inscription "Ordem e Progresso" (Order and Progress). It is meant to represent the state of Pará, a part of Brazilian territory in the northern hemisphere.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!