Europe's Gravity-Mapping GOCE Satellite Faces Big Fall from Space

A European-built satellite built to map Earth's gravity like never before is about to fall victim to the planet's ever-present gravitational pull.

The European Space Agency's Gravity field and steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer, or GOCE for short, is nearly out of fuel and will make a nosedive to Earth this month after more than four successful years studying the planet's gravitational field.

The doomed GOCE satellite launched in 2009 into a Sun-synchronous, near-circular polar orbit by a Russian Rockot vehicle from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome. In today’s dollars, the mission is a $475 million effort, including launcher and operations. [6 Biggest Spacecraft to Fall Uncontrolled From Space]

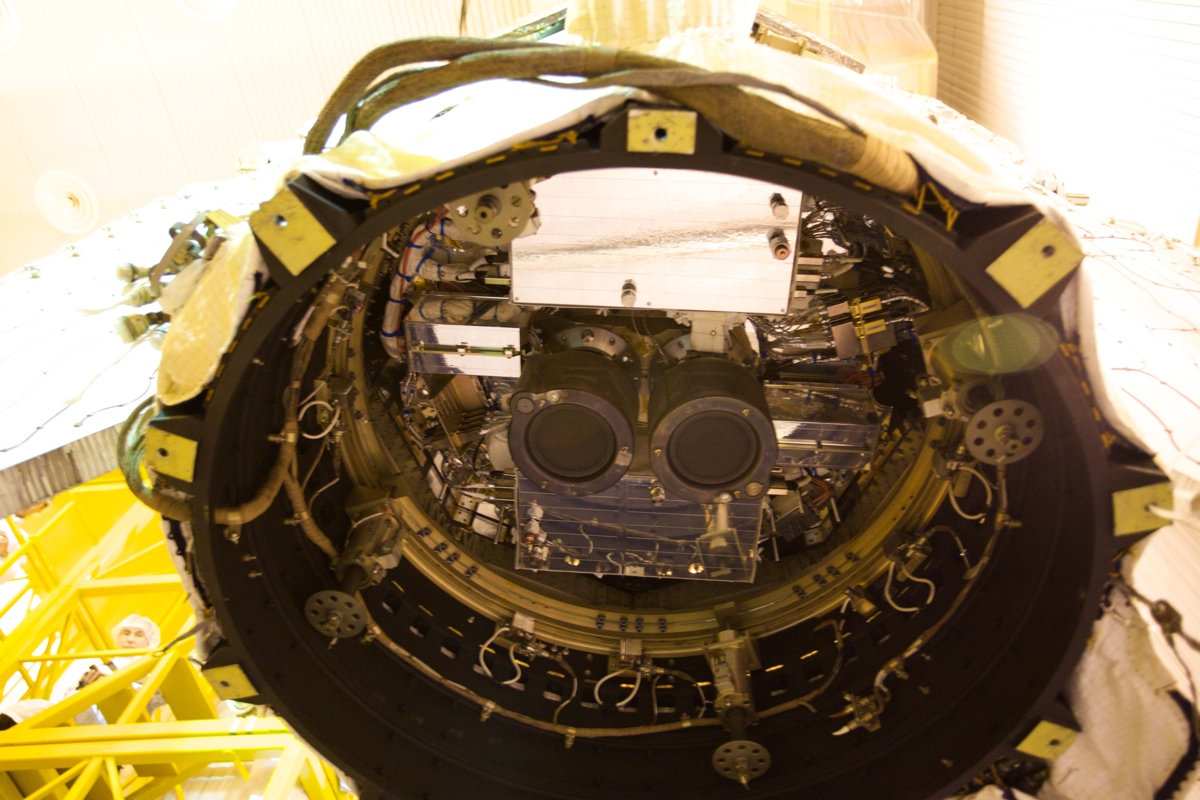

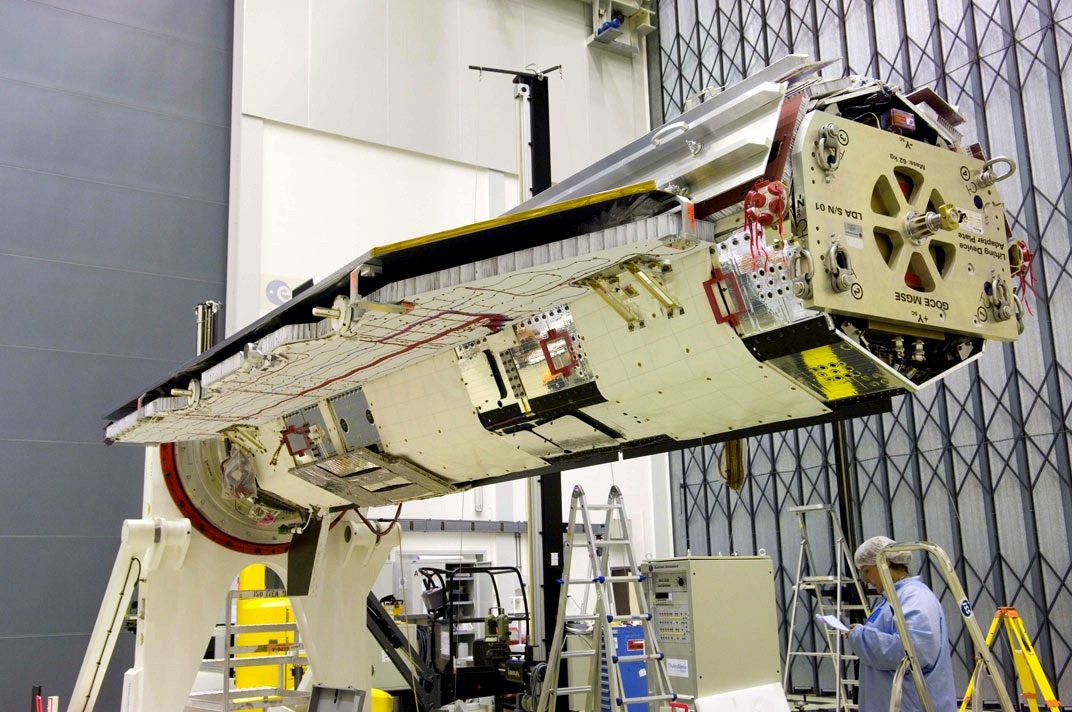

The sleek 1.2-ton (1,100 kilograms) GOCE satellite is outfitted with an Xenon-fueled ion engine that compensated for any drag by generating carefully calculated thrusts. It skimmed above Earth at a low orbit of about 139 miles (224 kilometers).

GOCE runs out of fuel in the mid- to end of October time period. Two or three weeks after that, the spacecraft is expected to tumble to Earth.

When the uncontrolled GOCE spacecraft plunges through the atmosphere, several pieces of the satellite will likely survive the ensuing fireball and reach the Earth's surface. But when and where that space debris will fall is not yet known.

GOCE satellite fragments to reach Earth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The debris zone area for GOCE's fall from space will be narrowed down closer to the time of spacecraft demise, ESA officials say. According to ESA estimates, up to 40 to 50 pieces of GOCE — making up about 500 pounds (250 kilograms) of the satellite's full mass — may survive the skyfall.

But given that two thirds of Earth is covered by oceans, and vast areas are thinly populated, the risk to life or property is gauged as very low, ESA officials have said. As has been the case in the past, an international campaign of space debris analysts will monitor the descent and provide updates as to the debris fallout location.

Recent examples of uncontrolled reentries that stirred up media, public and analytical attention were the 2011 re-entries of NASA's Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), the German Röntgensatellit ROSAT satellite, followed by Russia's failed Phobos-Grunt mission to Mars in 2012.

Global GOCE-watch campaign

A global campaign of space groups will monitor the GOCE descent, a wait-and-watch group of 12 member agencies within the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC). ESA's Space Debris Office will issue re-entry predictions and risk assessments regarding the fall of GOCE, updating its Member States and also relevant safety authorities.

Re-entry experts in Europe use a computer modeling tool, Space Craft Atmospheric Re-entry and Aero-thermal Breakup, or SCARAB. As an integrated system for destructive re-entry analysis, SCARAB can forecast the aerodynamic and aero-heating loads on GOCE, down to what pieces of the spacecraft might reach the Earth's surface.

Holger Krag of ESA's Space Debris Office located at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany said that a detailed break-up analysis on GOCE using SCARAB has been performed.

GOCE satellite leftovers

"GOCE is a precise gravity measurement experiment, hence, there are no particularly critical components onboard … neither heat-resistant optics nor any toxic materials, Krag told SPACE.com.

GOCE has an electric propulsion system, hence the tanks are rather small.

"The Scarab results reveal that the GOCE reentry does not show any particularities with respect to other uncontrolled re-entries," Krag said. "Typical spacecraft in the one-ton class have 20 percent to 30 percent of their mass surviving the re-entry. You may assume that also GOCE operates in the same range, but there were no exotic findings among the fragments."

Krag said that GOCE components that are the typical suspects for surviving re-entry are a tank and magnetotorquers, as the spacecraft has no reaction wheels. "The rest of the components are ‘unrecognizable’ incomplete, irregular fragments," he added.

Remaining fuel uncertain

Rune Floberghagen, GOCE mission manager, told SPACE.com that the best engineering estimates point to the spacecraft running out of fuel around Oct. 19 or 20, followed by two to three weeks before re-entry.

"However, we do have uncertainties in the estimate of the remaining fuel," as well as other uncertainties that can influence the longevity of GOCE's stay in space," Floberghagen said. "In other words, the flight period might be a bit shorter or a bit longer."

GOCE spacecraft operations manager Christoph Steiger said that once GOCE runs out of fuel, its orbit will start decaying. [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

"We will initially keep operating the spacecraft, switching it off when its subsystems stop working due to the harsh environmental conditions at lower altitudes," Floberghagen said.This will mark the end of activities for the GOCE flight control team, he added.

Wealth of data

"We have collected a wealth of science data over the last four and a half years," Steiger told SPACE.com. The spacecraft has lasted much longer than the originally planned 20 months thanks to the low solar activity in the last few years," he said.

Steiger said that to get even more precise gravity measurements, in its last year of life the orbit of GOCE was lowered from 158 miles (255 km) down to an extremely low altitude of only 139 miles (224 km).

"The results are fantastic … we have obtained the most accurate gravity data ever available to scientists," Steiger added.

The looming doom of GOCE has some mission scientists like Steiger reflecting back on what has been a successful space science flight.

"Personally, I do feel sorry to see GOCE come to an end, a project on which I have spent seven intense years. Then again, it is also a good feeling to know that we have really gotten the most out of this mission before its natural end … much more than what we could have hoped for," Steiger said.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin's new book "Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration" published by National Geographic. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.