Neutrino Telescopes Launch New Era of Astronomy

The recent discovery of neutrino particles bombarding Earth from outer space has ushered in a new era in neutrino astronomy, scientists say.

Neutrinos are produced when cosmic rays interact with their surroundings, yielding particles with no electrical charge and negligible mass. Scientists have wondered about the source of cosmic rays since they were discovered, and finding cosmic neutrinos could provide clues about the origin of the mysterious rays.

In November, a team of scientists announced the discovery of cosmic neutrinos by the giant IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica. [Neutrinos from Beyond the Solar System Found (Images)]

"We now have the opportunity to determine what the sources are, if we are indeed seeing sources of cosmic rays," said Francis Halzen, principal investigator of the IceCube observatory and a theoretical physicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "The big difference why it's new astronomy is that we are not using light, we are using neutrinos to look at the sky."

Cosmic visitors

Neutrinos are the social misfits of the particle world — they rarely interact with matter. Produced in some of the most violent, but unknown, events in the universe, they travel to Earth at close to the speed of light and in straight lines, which reveals information about their origin. Supernovas, active galactic nuclei and black holes are some of the possible sources for these ghostly particles.

Until recently, scientists had only detected neutrinos beyond Earth from the sun or from a supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud in 1987. No neutrinos from distant cosmic sources had been seen.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

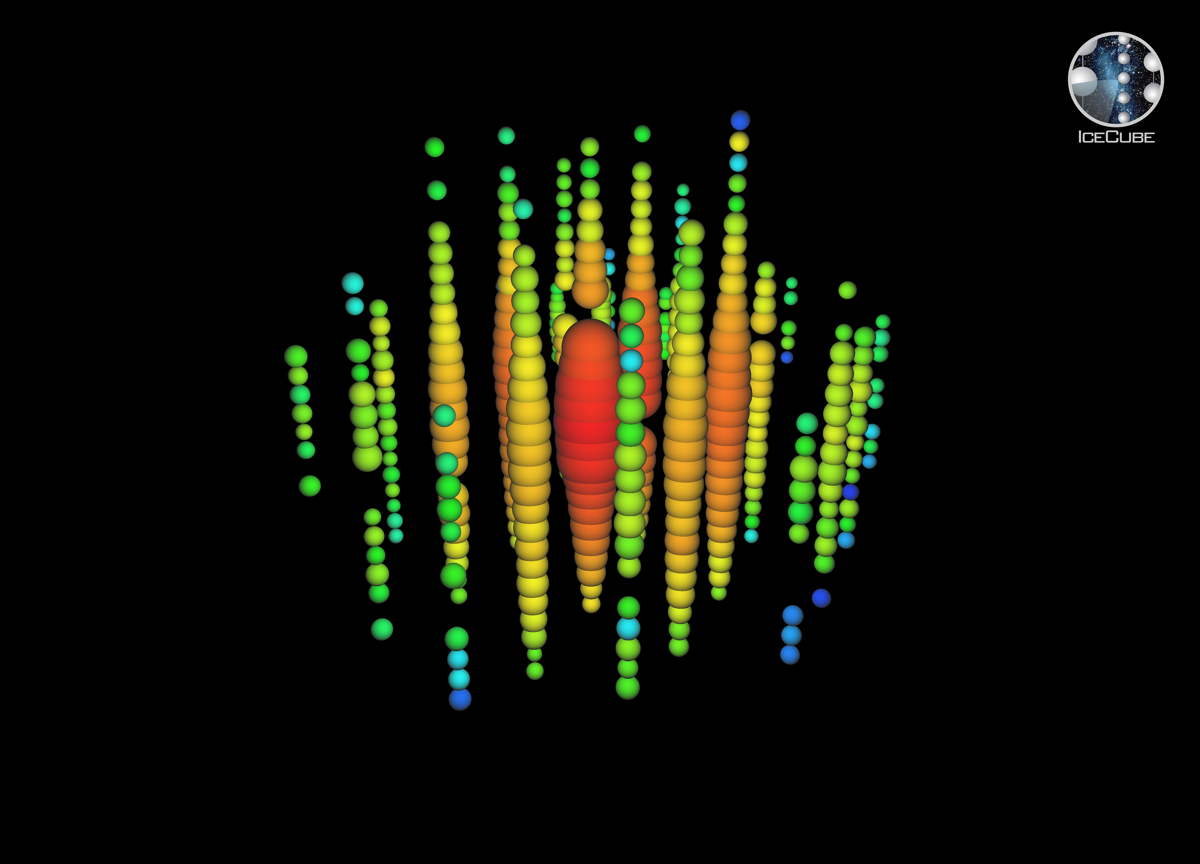

But in April 2012, IceCube recorded two neutrinos with extremely high energies — almost a billion times that of the ones found in 1987 — that could only have come from a high-energy source outside the solar system. After looking deeper into the data, scientists found a total of 28 high-energy neutrinos with energies greater than 30 teraelectronvolts (TeV), reporting their finding in the journal Science.

The finding opens the door to a new kind of astronomy that would "image" the sky in the light of neutrinos, rather than photons. "Each time we find another way to make a picture of the sky — using gamma rays, X-rays, radio waves — you have always been able to see things you never saw before," Halzen told SPACE.com.

The successful completion of IceCube and the prospect of other telescopes on the horizon have set the neutrino world abuzz.

"It is the point in time when it becomes real," said Uli Katz, an astrophysicist at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany, who is helping spearhead KM3NeT, a planned neutrino telescope in the Mediterranean Sea.

Neutrino telescopes

The idea of neutrino detectors goes back to the 1950s, when Clyde Cowan and Frederick Reines first detected neutrinos from a nuclear reactor. Later, scientists detected solar neutrinos and atmospheric neutrinos.

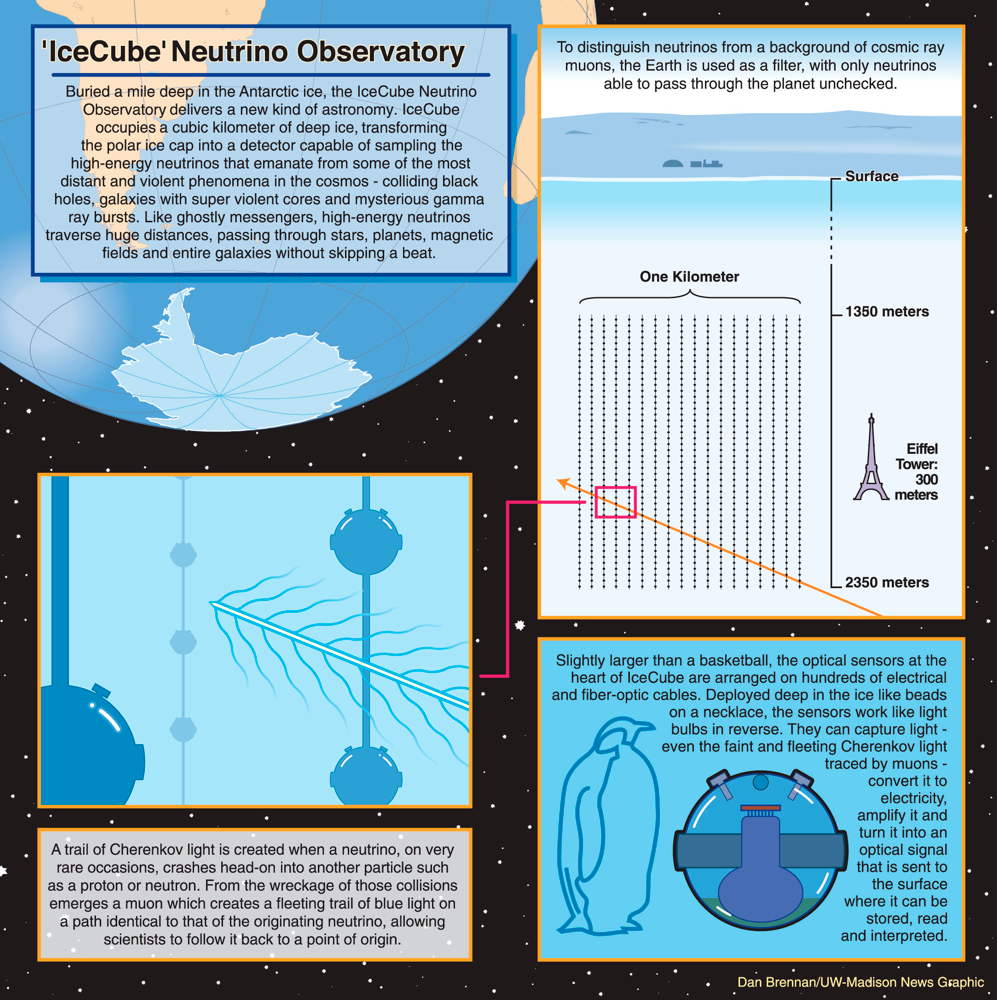

Because neutrinos interact so weakly with other particles, you have to have a very large amount of matter in order to detect them. When neutrinos smash into protons or neutrons inside an atom, they produce secondary particles that give off a blue light called Cherenkov radiation. You need a large, transparent detector shielded from daylight to see them, so scientists build them deep underwater or embedded in ice.

The Deep Underwater Muon And Neutrino Detector (DUMAND) Project was a proposed underwater neutrino telescope in the Pacific Ocean near the island of Hawaii. The observatory would have stretched nearly 0.25 cubic miles (1 cubic km) of ocean more than 3 miles (5 km) beneath the surface. Started in 1976 but canceled in 1995, DUMAND paved the way for successor projects.

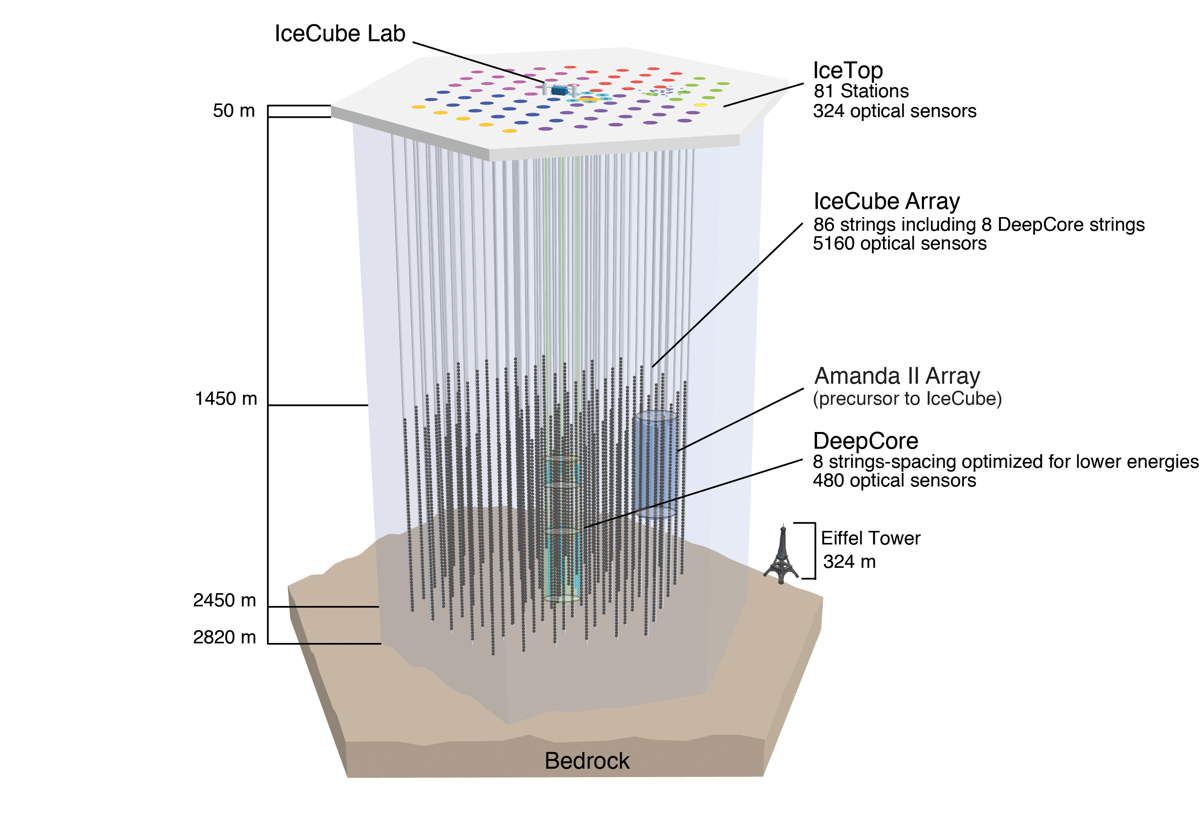

Scientists built the Antarctic Muon And Neutrino Detector Array (AMANDA) in the ice beneath the South Pole, which ultimately became part of the IceCube observatory. IceCube, which was completed in 2010, consists of a cubic kilometer grid of sensors embedded below 4,900 feet (1,500 m) of ice.

In Europe, scientists are developing plans for KM3NeT, which will span 1.2 cubic miles (five cubic kilometers) in the Mediterranean. And scientists at the Baikal Neutrino Telescope in Russia's Lake Baikal, the largest freshwater lake by volume in the world, are planning to build the Gigaton Volume Detector (GVD), which would be one cubic km.

The latest neutrino telescopes will enable more than just new astrophysics. Scientists are starting to use them to look for dark matter, the unknown substance that makes up roughly 85 percent of the total matter in the universe. In addition, being able to detect high-energy neutrinos will enable new particle physics that even the best particle accelerators can't achieve.

"I expect lot of effort will be invested to increase this field in its capabilities," Katz said.

Editor's Note: This story was updated Jan. 21 to correct the location of the neutrino signal in 1987 from a supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.