Ancient Star May Be Oldest in Known Universe

Astronomers have found what appears to be one of the oldest known stars in the universe.

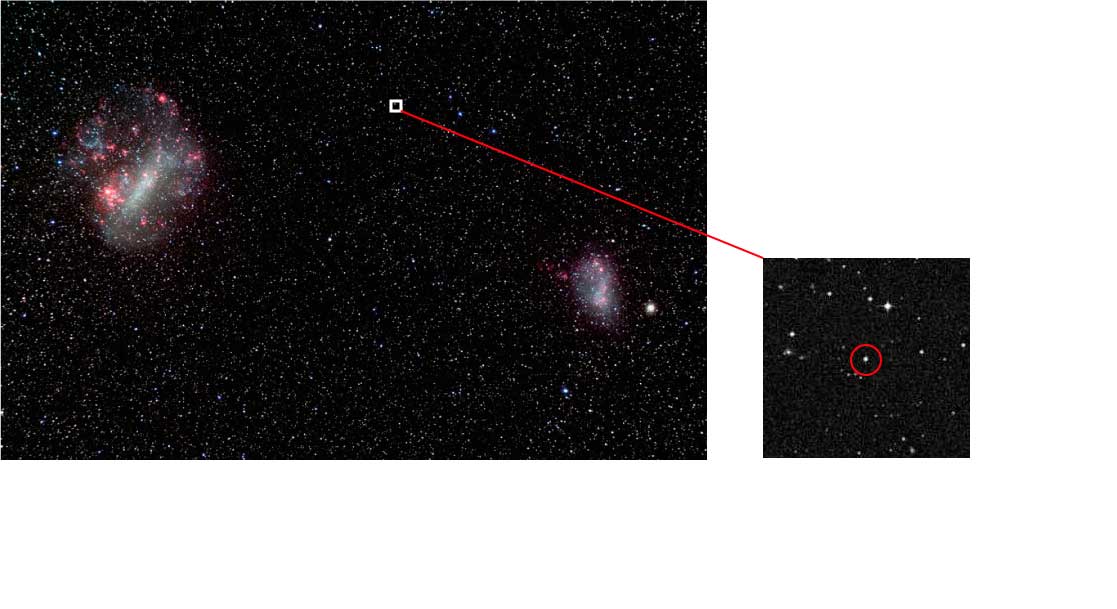

The ancient star formed not long after the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, according to Australian National University scientists. The star (called SMSS J031300.362670839.3) is located 6,000 light-years from Earth and formed from the remains of a primordial star that was 60 times more massive than the sun.

"This is the first time that we've been able to unambiguously say that we've found the chemical fingerprint of a first star," lead scientist Stefan Keller, of the ANU Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, said in a statement. "This is one of the first steps in understanding what those first stars were like. What this star has enabled us to do is record the fingerprint of those first stars." [See amazing photos of supernova explosions]

Scientists think SMSS J031300.362670839.3 is probably at least 13 billion years old, though they do not know its exact age, Anna Frebel, an MIT astronomer associated with the research, said

Keller and his team found that the star actually has an unexpected composition. Astronomers thought that primordial stars — like the one that SMSS J031300.362670839.3 formed from — died in huge supernova explosions that spread large amounts of iron throughout space.

However, the new observations have shown that SMSS J031300.362670839.3's composition harbors no iron pollution. Instead, the star is mostly polluted by lighter elements like carbon, ANU officials said.

"This indicates the primordial star's supernova explosion was of surprisingly low energy," Keller said. "Although sufficient to disintegrate the primordial star, almost all of the heavy elements such as iron, were consumed by a black hole that formed at the heart of the explosion."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists also found that the early star's composition is very different from the sun.

"To make a star like our sun, you take the basic ingredients of hydrogen and helium from the Big Bang and add an enormous amount of iron — the equivalent of about 1,000 times the Earth's mass," Keller said. "To make this ancient star, you need no more than an Australia-sized asteroid of iron and lots of carbon. It's a very different recipe that tells us a lot about the nature of the first stars and how they died."

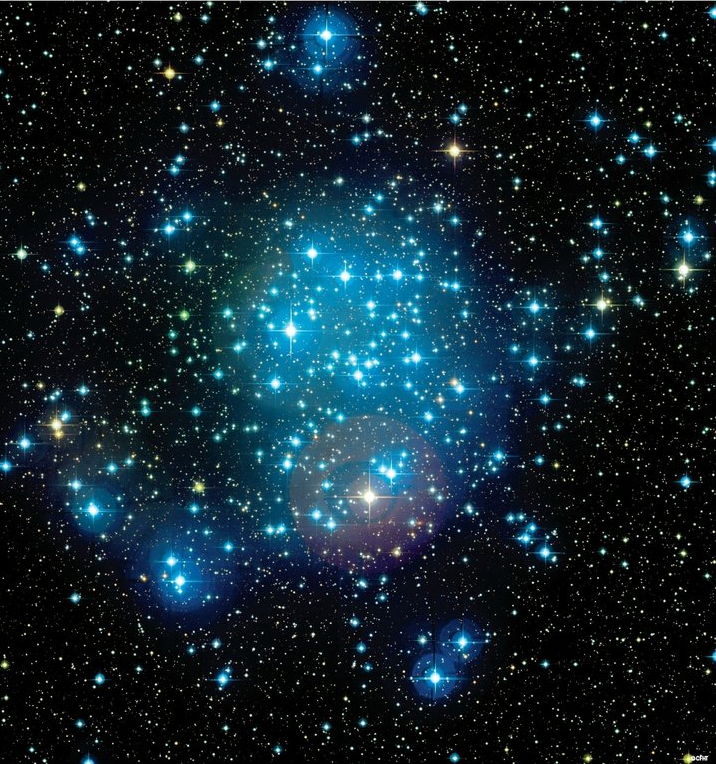

Because of its low mass, the star, located in the Milky Way, has a long lifetime, Anna Frebel, an MIT astronomer associated with the research, told Space.com via email.

Keller and his team found SMSS J031300.362670839.3 by using the ANU SkyMapper telescope. SkyMapper is surveying the sky at the Siding Spring Observatory in Australia to produce the first-ever digital map of the sky in the Southern Hemisphere. They confirmed their observations using the Magellan telescope in Chile.

The new results are detailed in the journal Nature.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.