NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope has just spotted Earth's cousin. Its next big find may be Earth's twin.

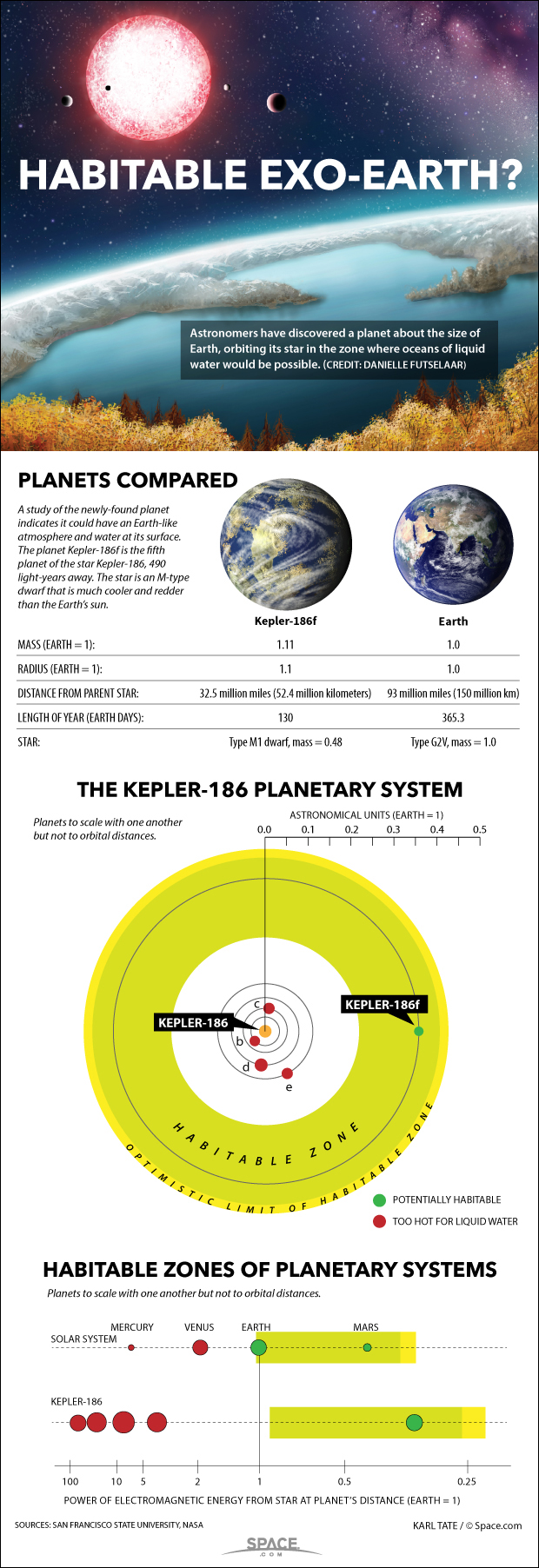

On Thursday (April 17), astronomers announced the discovery of Kepler-186f, the first Earth-size alien planet ever found in its host star's "habitable zone" — that just-right range of distances that could allow liquid water, and perhaps life, to exist on a world's surface.

While the discovery is a watershed moment, Kepler-186f still falls short of the ultimate prize in exoplanet science: a true "alien Earth." That's because the newfound world orbits a red dwarf, a star much smaller and dimmer than our own sun. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

"One of the things we've been looking for is maybe an Earth twin, which is an Earth-size planet in the habitable zone of a sunlike star," said Kepler scientist Tom Barclay, a member of the team that found Kepler-186f.

Kepler-186f is an "Earth-size planet in the habitable zone of a cooler star," Barclay told Space.com. "So, while it's not an Earth twin, it is perhaps an Earth cousin. It has similar characteristics, but a different parent."

But that first alien Earth may lurk somewhere in Kepler's huge data set, just waiting to be pulled out by mission scientists.

The $600 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009 to determine how common Earth-like planets are in the Milky Way galaxy. The observatory was designed to detect alien worlds using the "transit method," in which scientists note the telltale brightness dips that result when a planet crosses, or transits, its star's face from Kepler's perspective.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kepler's original planet hunt ended last May, when a glitch robbed the telescope of its superprecise pointing ability. But as the Kepler-186f announcement attests, the finds keep rolling in from the mission — and likely will do so for quite some time.

And the best may be yet to come from the prolific planet hunter.

"There's still a year of data that we have to fully analyze," Kepler principal investigator Bill Borucki, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., told Space.com last month. "The data in there is of the smallest planets with the fewest transits that are the most valuable discoveries."

Kepler has already shown that small, rocky planets like Earth are common throughout the galaxy — something astronomers didn't know before the observatory got off the ground.

Before Kepler, planet hunters had been finding lots of "hot Jupiters" — gas giants that orbit extremely close to their host stars. These big planets likely formed farther out but then spiraled in over time, and many researchers speculated that such migrations would rid the system of any small, rocky worlds that had formed — sending them crashing into the star or ejecting them into the depths of space.

"The thought was, before the mission launched, that there might not be any [other] Earths at all. We might very well be the only Earth-like planet in the entire galaxy," Borucki said. "Kepler has proven this completely wrong. It has proven there is an enormous number — at least a billion, several billion, probably — of Earth-size planets in the galaxy."

And scientists may soon have some new Kepler data to start analyzing. The team has proposed a new mission for the observatory called K2, which would allow Kepler to keep hunting for exoplanets (albeit in a modified fashion) and look for other phenomena and objects as well, such as supernova explosions, asteroids and comets.

The K2 proposal is under review at NASA headquarters, and a final decision is expected in the next month or so, team members have said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.