Solar Eclipse Will Transform Sun into 'Ring of Fire' Next Week

Editor's update (April 28): The first solar eclipse of 2014 will be webcast live for observers who can't witness it firsthand in Australia. To follow the webcasts, visit: Solar Eclipse Webcasts by Slooh, Virtual Telescope Project

The sun will look like a ring of fire above some remote parts of the world next Tuesday (April 29) during a solar eclipse, but most people around the world won't get a chance to see it.

Whereas lunar eclipses occur only when there's a full moon, and solar eclipses only happen during a new moon. Half the world saw a lunar eclipse during the full moon on April 15. When a lunar eclipse occurs, it usually means there is also a solar eclipse at the preceding or following new moon.

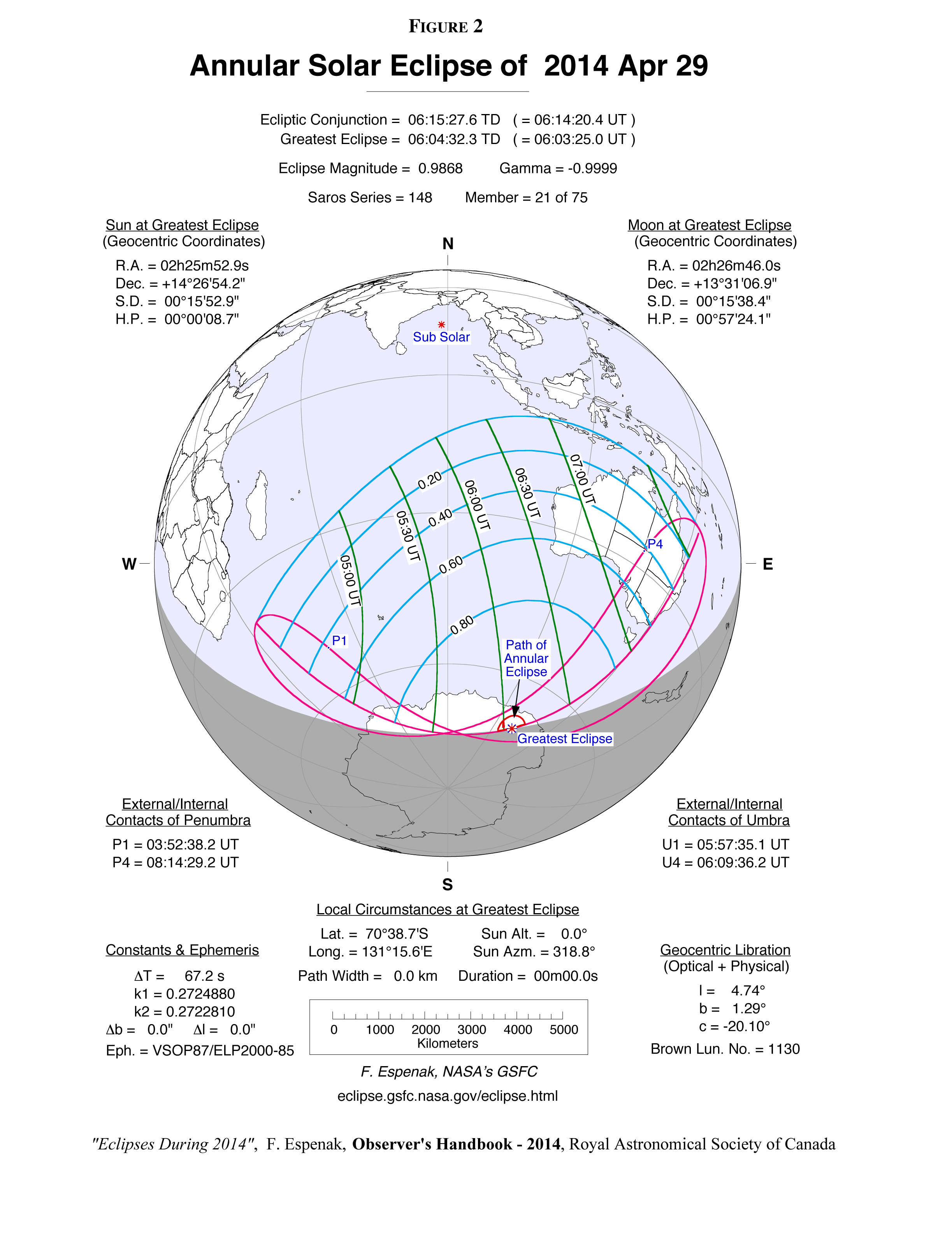

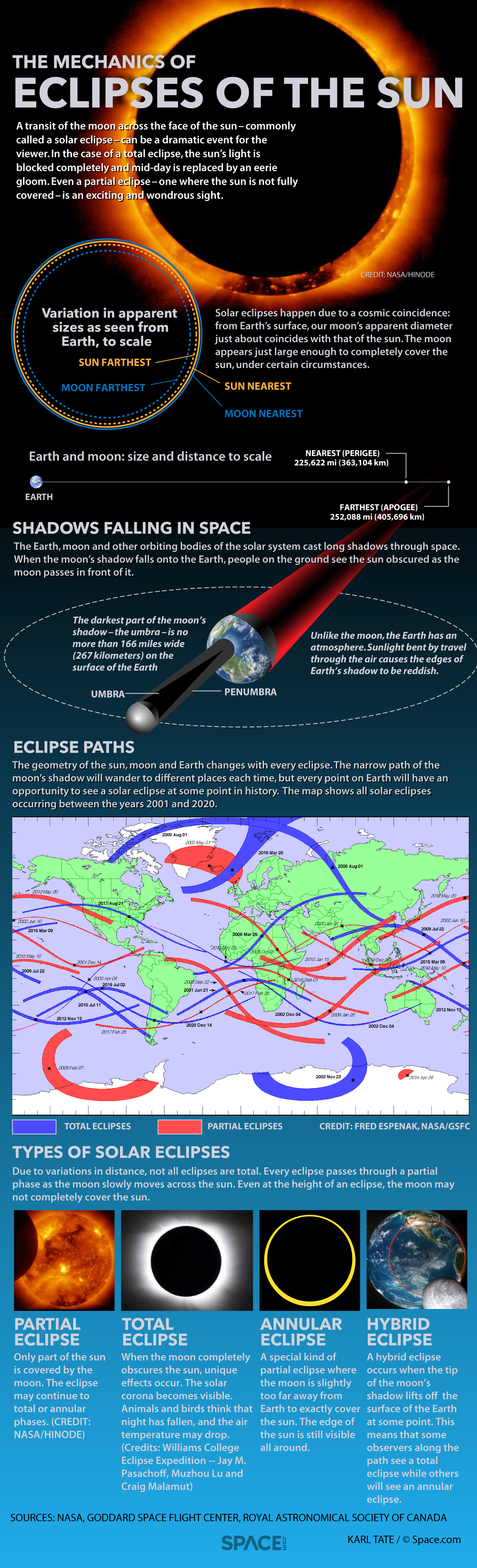

Tuesday's solar eclipse is known as an "annular" — rather than "total" — lunar eclipse. That’s because Tuesday's eclipse will occur when the moon is close to its farthest distance from the Earth, making it too small to cover the sun completely. The resulting effect looks like a ring of fire, called an "annulus," appears around the silhouette of the moon. ['Ring of Fire' Annular Solar Eclipse of April 29, 2014 (Visibility Maps)]

But most people won't see the whole eclipse. The only place in the world where this annular eclipse will be visible is a small area in Antarctica. However, partial phases of the eclipse will be visible in other places. Most of those areas are in the ocean — rarely traveled ocean, in fact — but the entire continent of Australia will get a good view.

The best view of the eclipse will be from the island state of Tasmania. From Hobart, the capital of Tasmania, the eclipse will begin with the moon taking a tiny nick out of the sun's edge at 3:51 p.m. local time (0551 GMT). Maximum eclipse will be at 5 p.m. (0700 GMT), and the sun will set at 5:17 p.m. (0717 GMT).

The farther north you go in Australia, the less the moon will cover the sun. In Sydney, the eclipse will begin at 4:14 p.m. and will be at maximum — 52 percent covered — at 5:15 p.m. The sun will set in eclipse two minutes later.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Skywatchers in the western parts of Australia will be able to see the end of the solar eclipse. In Perth, the eclipse begins at 1:17 p.m. (0517 GMT), is at maximum (59 percent) at 2:42 p.m. (0642 GMT), and ends at 3:59 p.m. (0759 GMT).

WARNING: Never look directly at the sun during an eclipse with a telescope or your unaided eye; severe eye damage can result. (Scientists use special filters to safely view the sun.)

Partial solar eclipses have the greatest potential for eye damage because at no time is the sun completely covered by the moon. The sun itself is no more dangerous during an eclipse. The danger comes from people's desire to look at it, to overcome the natural reflex that forces us to look away from the sun.

The safest way to view a solar eclipse is to project its image. The easiest way to do so is with a pinhole camera. The longer the projection distance from the pinhole to the viewing screen, the larger the sun will appear. Natural pinholes are often formed by gaps between tree leaves, covering the ground beneath with miniature eclipses. A small mirror on a window ledge can project a fine image on the ceiling or far wall, suitable for viewing by a whole room full of people.

You should never attempt to look directly at the sun without a proper solar filter, available from telescope stores, planetariums and science centers. This is especially true if you're viewing it through binoculars or a telescope. There is no way to create your own safe filter from ordinary materials, so don't risk it.

Editor's Note: If you live in the populated visibility path and snap an amazing picture of the April 29 solar eclipse, you can send photos, comments, and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.