Odd Exoplanet Find Hints at Many Earth-Like Worlds

Astronomers have for the first time detected a rocky alien world in an Earth-like orbit around just one star in a two-star system.

The new find suggests that such worlds may be common, and the strategy used to discover the planet could help reveal more exoplanets in the future, researchers say.

Although Earth orbits a single star, most sun-like stars are binaries, two stars orbiting each other as a pair. In fact, there are many three-star systems, and even some that harbor up to seven stars. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

Worlds that orbit around twin suns, as portrayed on Luke Skywalker's fictional home world Tatooine in "Star Wars," are known as circumbinary planets. The first real-life circumbinary planet ever discovered by astronomers is Kepler-16b, a gas giant found orbiting the star Kepler-16 about 200 light-years from Earth.

In another scenario for binary stars, planets can circle one star but not the other. These planets are known either as circumprimary or circumsecondary planets, depending on which star they orbit in the binary system — the brighter or more massive star, referred to as the primary star, or the fainter or less massive one, called the secondary star.

Astronomers have discovered circumprimary and circumsecondary planets before; for instance, Alpha Centauri Bb is a rocky planet orbiting Alpha Centauri B, the dimmer of the Alpha Centauri AB binary system about 4.2 light-years from Earth. However, Alpha Centauri Bb orbits just 0.04 AU away from its star. (One astronomical unit or AU is the distance between Earth and the sun — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

Now, scientists have detected a rocky planet circling the smaller, dimmer member of a binary system, at the same distance from its star as Earth is from the sun. The scientists detail their findings online today (July 3) in the journal Science.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

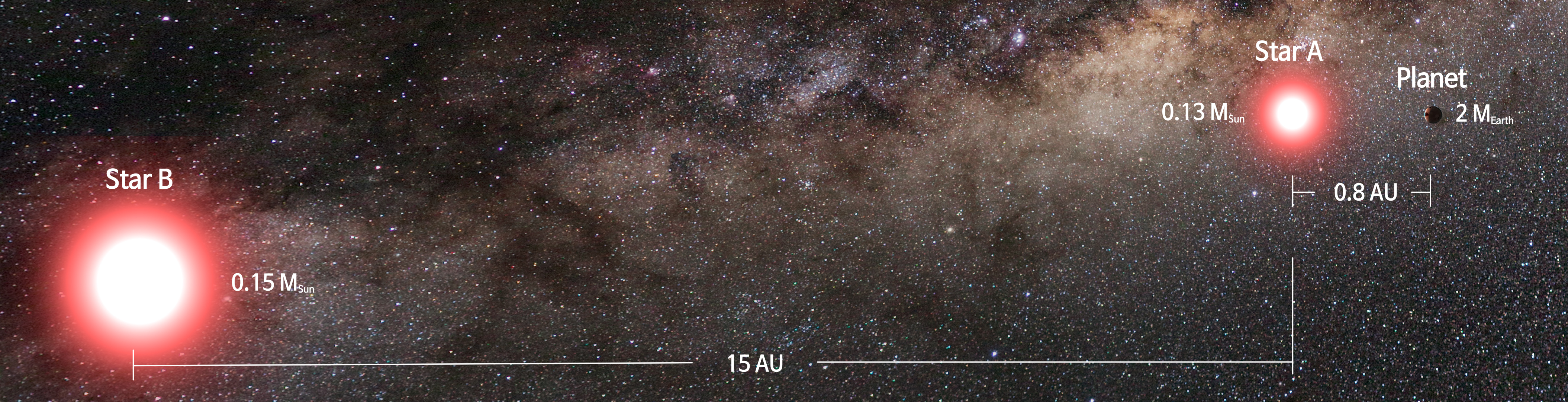

The exoplanet in question has the alphabet soup name of OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb. It has about twice the mass of Earth and lies about 3,000 light-years from Earth.

Both stars in the system are red dwarfs that are much colder and dimmer than the sun. The planet's host star is about 0.11 to 0.14 times the sun's mass, while its brighter companion is about 0.12 to 0.17 times the sun's mass. The exoplanet orbits roughly 0.8 AU from its star. In comparison, the planet's host star lies 10 to 14 AU from its companion, about the same distance between Saturn and the sun.

Although OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb is closer to its star than Earth is to the sun, it is much colder because its host star shines 400 times less brightly than the sun. This means the exoplanet does not lie within its star's habitable zone, the region around a star warm enough for a world to have liquid water on its surface. As such, this exoplanet is much colder than the Earth, with a surface temperature of about minus 350 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 213 degrees Celsius), researchers estimate — a little colder, in fact, than Jupiter's icy moon Europa.

It was a mystery until now whether an Earth-sized planet could form at an Earth-like distance from a star with a companion nearby. Scientists had suggested the close presence of a companion star could disrupt the protoplanetary disk of matter that produces worlds.

"It's very interesting such planets could form and survive," study lead author Andrew Gould, an astronomer at The Ohio State University in Columbus, told Space.com.

This new finding "greatly expands the potential locations to discover habitable planets in the future," study co-author Scott Gaudi, an astronomer at The Ohio State University, said in a statement.

Although "half the stars in the galaxy are in binary systems, we had no idea if Earth-like planets in Earth-like orbits could even form in these systems," he added.

In fact, this discovery hints that rocky planets may be very common around single members of binary pairs. The researchers calculated that there was only a 40 percent that the data they used would detect such a world based on the three years of data they had from the OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) survey. If the detection of this exoplanet was not merely a statistical fluke, it suggests that such worlds may be very common, Gould said.

The scientists detected OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb by noticing a one-day dimming of light in data collected by the OGLE telescope in 2013.

Strong gravitational fields can distort light in noticeable ways, a phenomenon known as gravitational microlensing. The exoplanet briefly dimmed light from a distant star 20,000 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius. [7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets]

"Without microlensing, it would be extremely difficult or near impossible to detect such a planet, a relatively small planet orbiting relatively far away from a very dim star," Gould said.

The researchers later noticed a huge brightening of the distant star in the Sagittarius constellation, a microlensing effect that suggested the exoplanet's host star had a companion star. The light signal that revealed the presence of the host star's companion also carried distortions the researchers could mine for details about the exoplanet, such as its mass and distance from its host. This discovery "gives us a new tool to find planets in the future," Gould said.

Gould praised the work of amateur astronomers, singling out frequent collaborator Ian Porritt of Palmerston North, New Zealand. Porritt watched for gaps in the clouds to get the first few critical measurements of the brightening in the light signal that revealed the exoplanet was in a binary system.

"Amateur astronomers really helped make this discovery possible," Gould said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us