The Milky Way: How to See It in the Summer Night Sky

Late summer is one of the best times of year to view the full splendor of our galaxy, the Milky Way.

The Milky Way used to be visible on every clear, moonless night, everywhere in the world. Today, however, most people live in places where it's impossible to see the Milky Way because of widespread light pollution caused by lights left on all night long. Seeing the Milky Way requires a special effort for most people, but it's well worth the trouble.

To see the Milky Way, you'll need to travel far from any city, to a wilderness area. Even in rural farming country, there are still a lot of bright lighting fixtures that wipe out the night sky. (I'm lucky; I live on a farm where my nearest neighbors are about half a mile away. And they don't have any bright lights in their yards, so I can see the Milky Way on any clear and moonless night.) [Stunning Photos of the Milky Way]

"Clear and moonless" are the key words here. Because of widespread air pollution, our skies are not as clear as they used to be. In particular, jet planes deposit water vapor into the sky, which serves to condense natural moisture, resulting in a haze that blocks the faintest stars. Some nights out here in the country, I can't see any more stars than I used to see 20 years ago, when I lived in a city.

The clearest skies appear just after a cold front passes through. Even then, you need to spend some time under a dark sky before your eyes become fully adapted to the darkness. It takes about 20 minutes for human eyes to become fully sensitive to faint light.

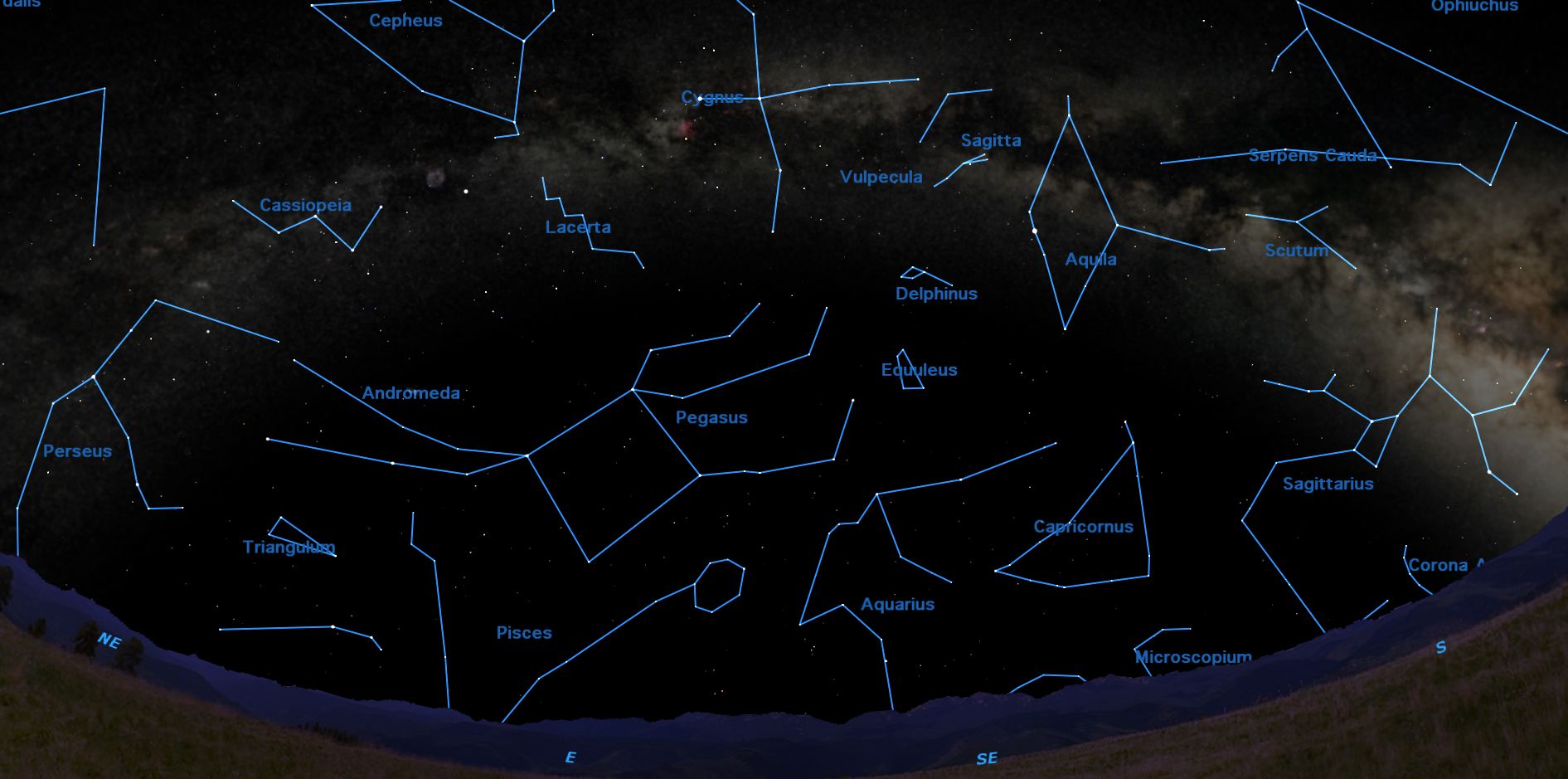

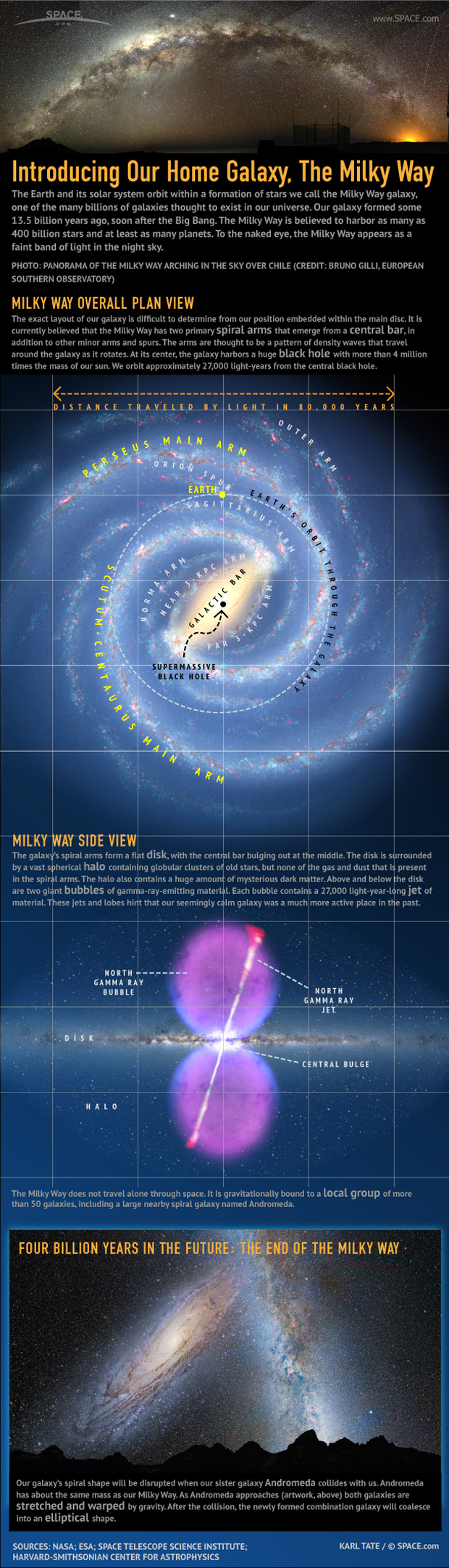

What does the Milky Way look like? Not like any of the photographs you see online, because those are made with cameras that accumulate light in ways the human eye cannot. What you will see is a faint, whitish glow, stretching in a huge arc from the southern to northeastern horizon. It has a mottled effect, kind of like a fluffy cloud. There are brighter areas, especially down toward the core of the galaxy in the southern part of the sky. There are also darker patches, where nearby clouds of interstellar dust block the light from beyond.

The most obvious of these dark nebulas is the Northern Coalsack, just below and to the right of the bright star Deneb in the constellation Cygnus. Just below Deneb is one of the brightest parts of the northern Milky Way, worth examining with binoculars. This is the North America Nebula, famous in pictures for its resemblance to the continent of North America. Under a very dark sky with binoculars, you may be able to see the "coast of California."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One thing you won't see in the Milky Way, either in binoculars or with the naked eye, is any color. Photographs register the reddish glow of hydrogen gas, but the light is too faint to trigger the color receptors in the human eye, so all you'll see are shades of gray.

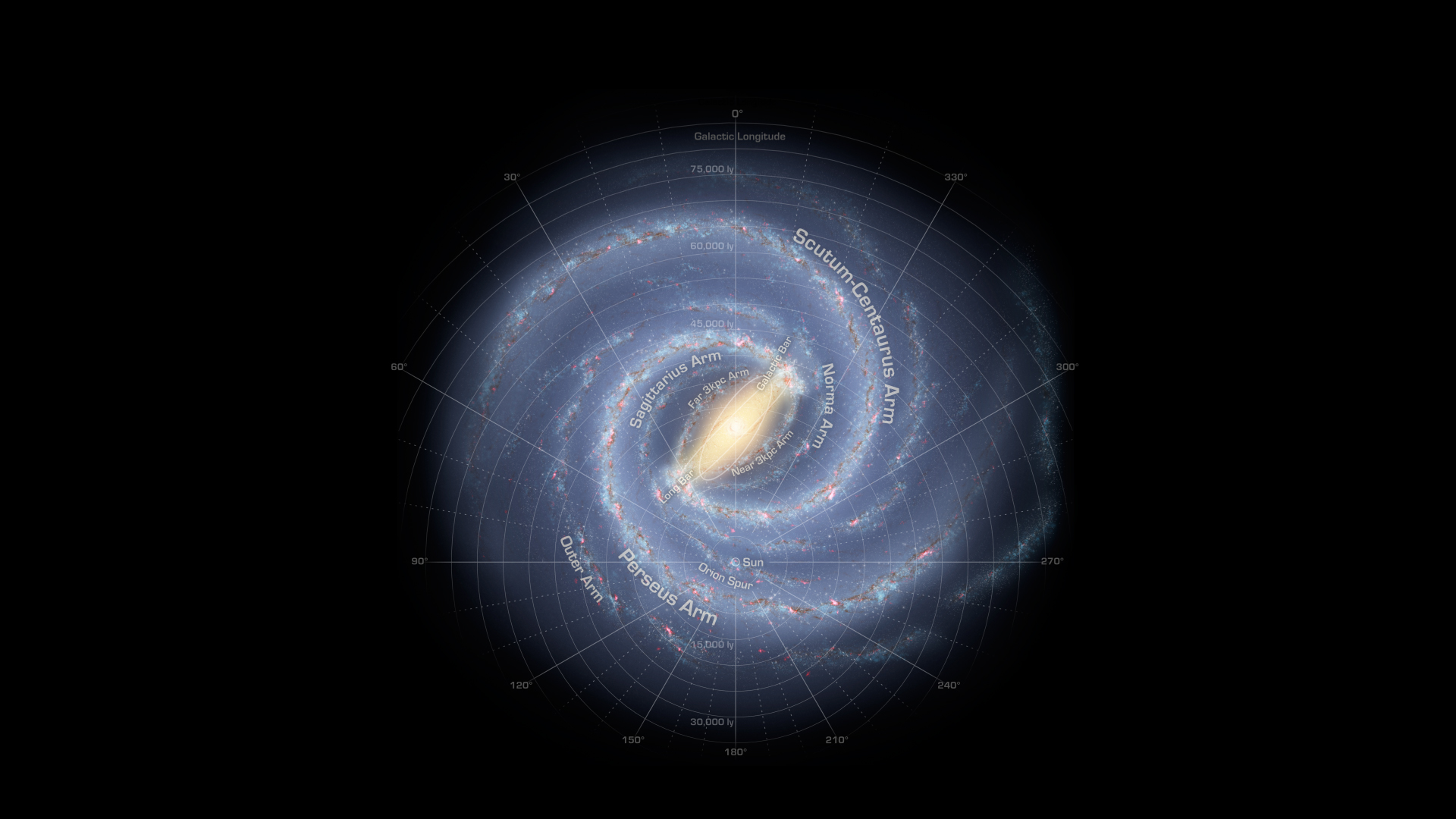

In the northern range of the Milky Way's arc, you'll see the constellations Cassiopeia and Perseus. When you look in that direction, you're looking outward from the spot within the wheel of the Milky Way toward its outer edge, and the stars are far less dense than when you look inward toward Sagittarius.

On a clear dark night, it's easy to see the grand sweep of the Milky Way galaxy, and to picture Earth's tiny island of life within its grand architecture.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.