Intriguing features photographed by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity probably don't have a biological origin, mission team members say.

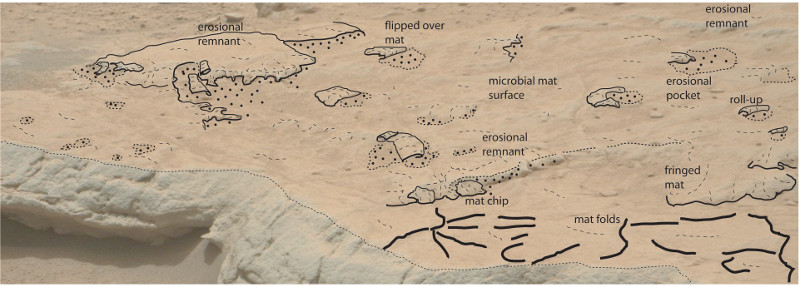

An outside researcher recently analyzed photos Curiosity took of an ancient sedimentary outcrop called Gillespie Lake, and noted some similarities to "microbially induced sedimentary structures" (MISS) here on Earth. Study author Nora Noffke, a geobiologist who is not a member of the Curiosity team, said the Gillespie Lake features could be consistent with a biological origin, but stressed repeatedly that this was just a hypothesis, and that she didn't regard the structures as proof of past Mars life.

Curiosity team members also noticed the Gillespie Lake structures (which include domes, cracks and pockets, among other shapes), said mission project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. But the rover team arrived at a different interpretation. [The Search for Life on Mars: A Photo Timeline]

"We really didn't see anything that can't be explained by natural processes of transporting that sand in water, and the nature of the rocks suggested that it was just a fluvial sandstone," Vasavada told Space.com.

"We do have several members of our team who are always keen to look out for things that might be caused by biological processes, but there was no reason, we felt, to explore that [option] at that site," he added. "It came down to nothing exceptional, from our point of view, that wasn't just a consequence of erosion of this sandstone."

Vasavada also stressed that he and the rest of the Curiosity rover team welcome analyses by outside researchers such as Noffke.

If mission scientists had decided to study Gillespie Lake more closely, they could have taken up-close photos using Curiosity's Mars Hand Lens Imager, Vasavada said, or drilled the rock to deliver powder to the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument, which is capable of detecting carbon-containing organic molecules.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Curiosity team did decide to drill into a layer of fine-grained mudstone dubbed Sheepbed, which lies directly beneath Gillespie Lake within a broader region near the rover's landing site called Yellowknife Bay.

SAM's analysis of the Sheepbed mudstone, along with other Curiosity observations, allowed the rover team to determine that Yellowknife Bay could have supported microbial life in the ancient past. About 3.5 billion years ago, the area was part of a lake-stream system that may have been habitable for millions of years, mission scientists said.

SAM also detected organics in the Sheepbed sample, marking the first definitive detection of life's building blocks on Mars.

"We feel that choice paid off," Vasavada said of the focus on Sheepbed.

Curiosity landed inside Mars' huge Gale Crater in August 2012, then spent almost a year exploring the Yellowknife Bay area. It departed for Mount Sharp — which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) into the Martian sky from Gale's Center — in July 2013 and reached the mountain's base last September.

Mount Sharp has been Curiosity's main science destination since before the rover's November 2011 launch. Mission team members want to drive Curiosity up through the mountain's foothills, reading a history of the Red Planet's changing environmental conditions in the rocks along the way.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.