Search for Alien Life Should 'Follow the Methane,' Scientists Say

In the search for life beyond Earth, the mantra has usually been, "Follow the water." But now, scientists say it may be possible for a waterless environment to give rise to alien life.

In a recent study, researchers at Cornell University proposed a formula for life that could thrive on Saturn's largest moon, Titan. With its freezing temperatures, seas of liquid methane and toxic atmosphere devoid of any liquid water, it may seem unlikely that Titan could give rise to life. But in such environments, it may be possible for there to be methane-based, oxygen-free extraterrestrial life, the researchers said.

On Titan, temperatures of minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 180 degrees Celsius) would make it difficult for processes like metabolism and reproduction to occur. But the theorized cell membrane, which houses the cell's organic matter, is composed of nitrogen instead of water, allowing it to do just that. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

On Earth, living cells have a strong, permeable, water-based barrier called a lipid bilayer membrane. But that concept works only in environments with liquid water, so when astronomers are searching for life outside our solar system, they zoom in on small rocky exoplanets orbiting inside a star's habitable zone — the band where liquid water can exist. But plenty of exoplanets (and even solar system moons) exist well outside this range, where liquid water can't exist.

So astronomers have long been fascinated by nonaqueous life, and even the possibility that Titan may host methane-based life. Other than Earth, it is the only place in our solar system with liquid seas on its surface. It also hosts a mysterious process that consumes hydrogen, acetylene and ethane, the researchers said. All of these elements flow down from the atmosphere but never quite make it to the surface. So, could life be gobbling them up?

To investigate this possibility, Jonathan Lunine, an astronomer at Cornell University, collaborated with James Stevenson, a graduate student, and his adviser, Paulette Clancy, both of whom work at Cornell's Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Department.

“We're not biologists, and we're not astronomers — but we had the right tools," Clancy said in a statement. "Perhaps it helped, because we didn't come in with any preconceptions about what should be in a membrane and what shouldn't. We just worked with the compounds that we knew were there and asked, 'If this was your palette, what can you make out of that?'"

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

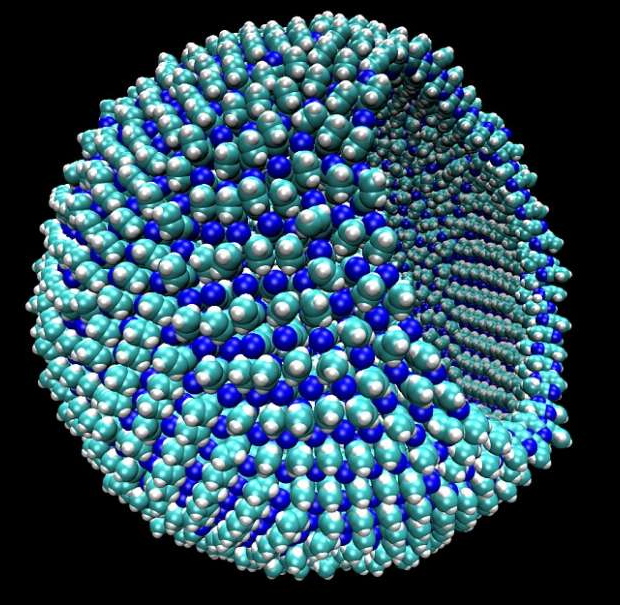

The researchers were able to model a cell that supports metabolism and reproduction but that's constructed from nitrogen, carbon and hydrogen-based molecules — all of which are known to exist within Titan's frigid seas. Like a lipid bilayer membrane here on Earth, it's both rigid and flexible, controlling the transportation of materials in and out of the cell.

They named their theorized cell membrane an "azotosome." (Azote is French for nitrogen, and lipsome is Greek for "lipid body," so "azotosome" means "nitrogen body.")

So far, the researchers have only shown that azotosomes could exist based on molecular simulations.

"Ours is the first concrete blueprint of life not as we know it," Stevenson said. The next step will be to demonstrate in the laboratory how such membranes function in a methane environment. In the long run, scientists might also be able to model possible observable indicators of alien life.

If life does exist on Titan, it would demonstrate that methane, in addition to water, could be an indicator of life, and that life could more easily populate the cosmos.

The findings were published Feb. 27 in the journal Science Advances.

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Shannon Hall is an award-winning freelance science journalist, who specializes in writing about astronomy, geology and the environment. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Nature, Quanta and elsewhere. A constant nomad, she has lived in a Buddhist temple in Thailand, slept under the stars in the Sahara and reported several stories aboard an icebreaker near the North Pole.