Doomed Russian Spacecraft Is Falling From Space, But Where Will It Fall?

Round and round it goes, but exactly where a failed Russian space cargo ship will fall to Earth on this week is a guessing game.

On April 28, Russia's uncrewed Progress 59 supply ship streaked into orbit atop a Soyuz launcher, intended to dock with the International Space Station. But shortly after liftoff, the vessel experienced technical difficulties. Subsequently, a Russian mission control team could not command the cargo vessel packed with nearly 3 tons of supplies.

Current forecasts predict that the Progress should fall to Earth in an uncontrolled, destructive nose-dive on Thursday (May 8) between 3:11 a.m. and 5:26 a.m. EDT (0711-0826 GMT). Some media reports from Russia are citing a Friday re-entry target. A more refined re-entry date and time will become available, according to experts tracking the spacecraft. [See photos of the Progress 59 cargo ship]

Now, there is some speculation that an explosion may have occurred as the Progress 59 separated from its Soyuz booster's third stage, sending the supply ship into a tail spin. Whatever the cause, the $51 million mission has been abandoned by Russia, leaving the falling Progress vehicle to a fiery demise in Earth's atmosphere.

Falling from space

The U.S. Joint Functional Component Command for Space's Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California is regularly monitoring the position of Progress 59.

In a statement last week, the JSpOC officials said they immediately began tracking the event and initiated the appropriate reporting procedures. They confirmed that the resupply vehicle is rotating at a rate of 360 degrees every five seconds. Additionally, the JSpOC has observed 44 pieces of debris in the vicinity of the resupply vehicle and its upper-stage rocket body.

The JSpOC will continuously track the cargo craft and debris, they said, "performing conjunction analysis and warning of any potential collisions in order to ensure spaceflight safety for all."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Living with uncertainties

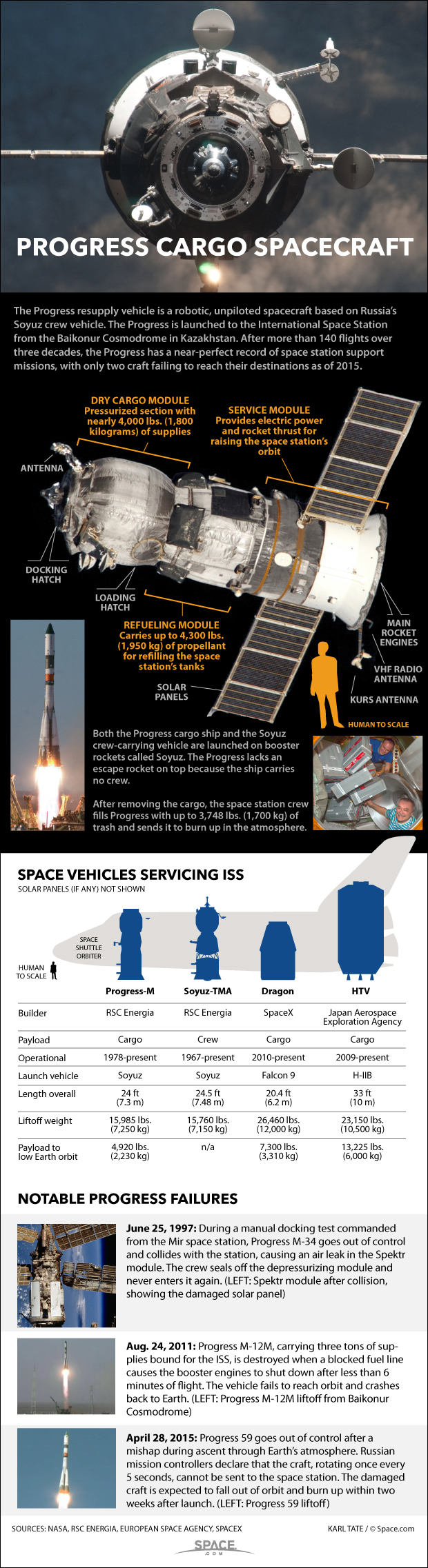

As a partner agency in the International Space Station program, the European Space Agency (ESA) is in close contact with the Russian and U.S. authorities regarding the Progress situation. [How Russia's Progress Cargo Ships Work (Infographic)]

At the moment there are large uncertainties when and where Progress 59 will fall to Earth, said Holger Krag, Head of ESA's Space Debris Office at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany.

"It depends on the solar activity," Krag told Space.com, "and the impact on the density of Earth's atmosphere, which is very poorly understood today."

Krag said things will become clearer a few hours before the actual re-entry of Progress. "We have to live with these uncertainties," he said.

In uncontrolled re-entry mode, Progress in principle could fall to Earth over any point of land or sea between approximately 51 degrees North and 51 degrees South latitudes, Krag said.

Will parts of Progress 59 survive?

There is the potential for pieces of Progress 59 to survive the fiery plunge through Earth's atmosphere and reach the surface, Krag said.

"With every re-entry of a large structure from space you can expect a small fraction to survive," Krag said. But there is an extremely small probability, he said, that somebody would be injured from the fall. [6 Biggest Spacecraft to Fall Uncontrolled from Space]

"That's because the number of objects that survive is small … and the area over which they are distributed is so huge and mostly unpopulated," Krag said. Also, the large fuel load onboard Progress should burn up before it reaches Earth, he said.

Bill Ailor, a Distinguished Engineer and a re-entry and space debris expert at The Aerospace Corporation in El Segundo, California, agrees with Krag's view.

Ailor said that the rule of thumb for re-entering spacecraft is that anywhere from 10 percent to 40 percent of the dry mass of the vehicle — the mass without propellants, liquids, and stored gas — will survive and impact the Earth's surface.

For Progress 59, that means that anywhere from roughly 1,540 to 6,615 lbs. (700 to 3,000 kilograms) of material will survive, Ailor told Space.com.

"This material will be spread out over a long, thin footprint that could be hundreds of kilometers long," Ailor said. "Given that there's a lot of ocean below the vehicle's orbit, it is most likely that no one will actually see the event."

Progress problems in orbit

The problem-plagued Progress 59 mission offers some clear messages, according to several space analysts. [Worst Space Debris Events in History]

"The [space station] is well supplied and other spacecraft can continue supplying it. So the major issue with this failure is what impact it will have on future launches of that version of the Soyuz rocket and the Progress spacecraft," said Marcia Smith, editor of SpacePolicyOnline.com.

"The Russians need to diagnose and correct whatever went wrong," Smith told Space.com. "Historically, they have been able to do that with alacrity. How long it takes this time is one test of the new organizational structure of the Russian space program that is putting the space industry and government space programs under a single leader."

Smith said that, on another level, the Progress incident further demonstrates how dependent space crews are on supplies from Earth.

The failure also underscores the advances in closed loop life support systems and refueling options that need to be achieved, Smith said, before people can be sent on missions far from the safety of our home planet.

Commonality of hardware?

James Oberg, a veteran reporter and writer on Russian space activities, said that the U.S. focus on the Progress 59 failure should be on any potential commonality of hardware between this doomed mission and equipment now being readied for follow-on missions, including for crews.

"Hopeful guesses can't be tolerated … any potential shared threat needs to be tracked down and eliminated, even if this means taking a lot of time," Oberg said.

Another issue, Oberg said, is the dearth of useful telemetry that has hobbled investigations from the start.

"It's long past time for the Russians to reactivate their own full-orbit Tracking Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS) links based on newly-deployed [Russian] Luch satellites apparently now monopolized by unmanned, particularly military spacecraft," Oberg added.

Toxic fuel on board

Another worrisome issue, Oberg added, is how much of the original load of toxic propellants remain onboard Progress when it re-enters."Perhaps we should hope we never find out the hard way," he said.

Falling propellant from space is an echo of the old controversy about the USA-193 spy satellite fuel components surviving re-entry in 2008, Oberg said.

When USA-193 malfunction in orbit, the U.S. military shot down the satellite with a modified SM-3 missile fired from the warship USS Lake Erie, stationed west of Hawaii.

"It was thought by many commentators at the time as a trumped-up excuse for an anti-satellite weapons test," Oberg said. "But I am convinced that with USA-193 some specific structural features and environmental exposure had created a genuine threat of delivery of significant toxic exposure onto a randomly selected spot on Earth."

But how much similarity there is between the case of Progress and USA-193 remains to be determined, Oberg said.

"Even once it's down the mystery likely will continue," he added. "I'm not encouraged by past lack of Russian candor on actual threats from the random fall of their spacecraft … such as Mars-96 [November 1996] with its plutonium batteries and Phobos-Grunt [January 2012] with eleven tons of unused propellant. Both probably dropped potentially hazardous fragments onto South America despite Russian insistence they 'safely' fell into the Pacific."

Threat odds of falling space junk

Don Kessler, a seasoned orbital debris expert, said that without a detailed computer model prediction, he would not know if the ground hazard exceeds the standard of one chance in 10,000 of injuring any individual.

"Like all objects that re-enter, it will most likely land in the ocean," Kessler told Space.com

"I would remind everyone that there are 7 billion people on Earth, so the one chance in 10,000 of any individual being harmed means there is only one chance in 70 trillion that the individual would be you," Kessler said.

"Anyone still frightened by these odds might want to play Powerball, since he or she would be 400,000 times more likely to win the Powerball jackpot than to be hit by the reentering debris," Kessler concluded.

Ground viewing

Meanwhile, satellite watchers are getting an eye-full of the soon-to-fall Progress.

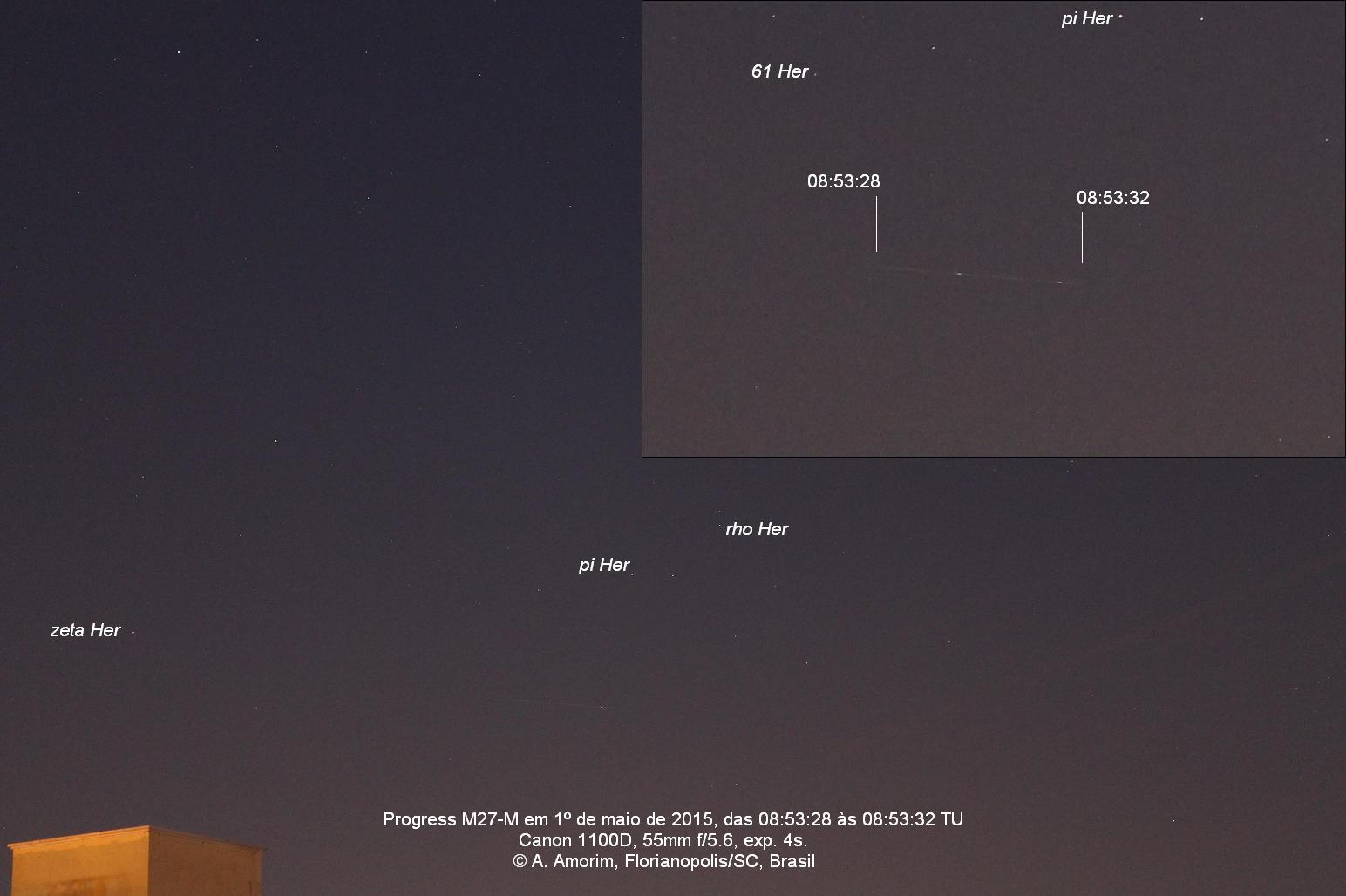

For example, Alex Amorim of Florianopolis in Brazil, caught the Progress cruising through his nighttime skies.

As his Canon camera took images every 4 seconds of the sky scene, Amorim visually observed the Progress by way of 10x50 binoculars.

"I estimated the maximum light variations between 2 and 2.5 seconds," Amorim told Space.com, counting 14 flashes in 31 seconds as the errant spacecraft tumbled by overhead.

"I'm crossing my fingers to observe the re-entry from here," he said.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin's 2013 book "Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration" published by National Geographic with a new updated paperback version released this month. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.