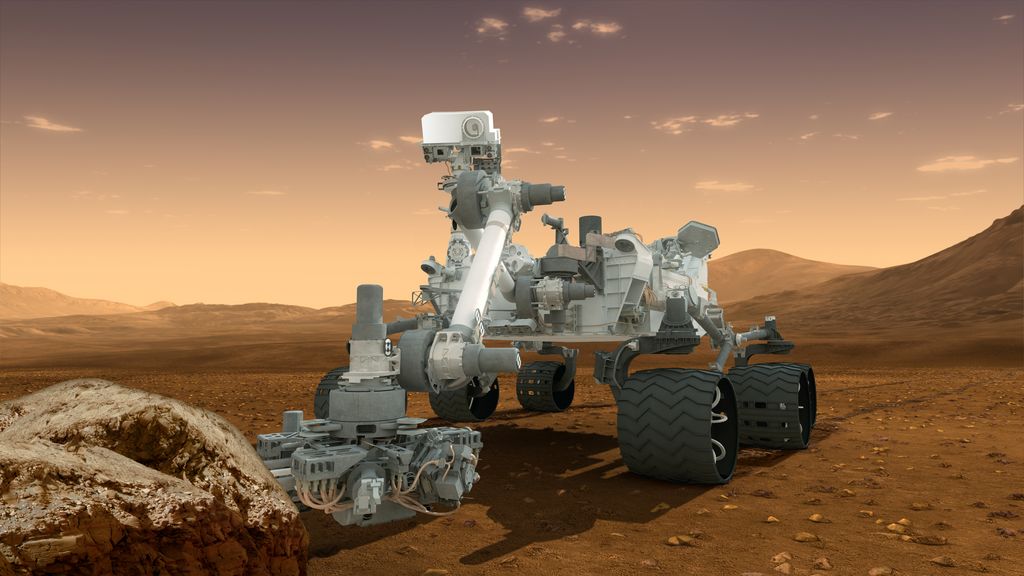

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has now been trundling across the Red Planet for three very productive and eventful years.

Curiosity landed on the night of Aug. 5, 2012, pulling off a dramatic and unprecedented touchdown with the aid of a rocket-powered "sky crane" that lowered the 1-ton rover gently to the Martian surface via cables.

The six-wheeled robot then set out to determine if its immediate environs — a 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) crater named Gale — could ever have supported microbial life. That work and more are chronicled in a new NASA video on Curiosity's discoveries on the Red Planet. [Latest Amazing Mars Photos by Curiosity]

Curiosity quickly succeeded in this main task. The rover's observations of rocks at an area near its landing site called Yellowknife Bay allowed mission scientists to deduce that Gale Crater supported a potentially habitable lake-and-stream system for long stretches in the ancient past — perhaps for millions of years at a time.

Curiosity departed the Yellowknife Bay area in July 2013, making tracks toward the foothills of the towering Mount Sharp, which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 km) into the Martian sky from Gale's center.

Mount Sharp's base has been Curiosity's primary destination since before the $2.5 billion mission's November 2011 launch. The rover team wants Curiosity to climb up through the mountain's lower reaches, reading a history of Mars' changing environmental conditions in the rocks along the way.

Curiosity reached the mountain in September 2014, rolling up to a Mount Sharp outcrop team members dubbed Pahrump Hills. The rover studied the Pahrump Hills area for about five months, drilling into rocks three separate times for analysis purposes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"That was an investment of time specifically because it was the first chance we got to see what the mountain was made out of," said Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "That was a great five months."

Curiosity left Pahrump Hillls in March to investigate outcrops higher up the mountain. Recently, the rover has been eyeing a geological "contact zone" where two distinct rock types come together.

"It's been an adventure, partly because we're on the mountain now, and driving is much more challenging," Vasavada told Space.com.

For example, thick sand and steep, slippery terrain thwarted Curiosity's first attempt to reach the contact zone. But the rover team found another route and got Curiosity where it needed to go.

The rover's work at Mount Sharp's base so far strongly suggests that liquid water deposited the bottom layers of the mountain, Vasavada said. These results extend the discoveries made at Yellowknife Bay, providing a more complete picture of the region.

"Our view of Gale Crater as an ancient habitable environment has grown tremendously, both spatially and through time in Mars history," Vasavada said. "And that's really what the rest of the mission will be about as well."

Curiosity currently sits at an elevation of perhaps 66 to 98 feet (20 to 30 meters) above Gale Crater's floor, he added. The rover team would ideally like to climb about 1,650 feet (500 m) up, to sample a number of different Mount Sharp layers.

Such mountaineering will take time — time that the mission team does not officially have at the moment. Curiosity is about halfway through its first two-year extended mission, which NASA approved after the two-year prime mission ended in 2014. The rover's handlers plan to keep applying for additional two-year extensions for the foreseeable future, Vasavada said.

He said he thinks they'll have a very good case for at least the next four years, because Curiosity remains productive and in good health.

The rover team has made a lot of progress in troubleshooting a glitch that recently cropped up in Curiosity's drilling mechanism, and concerns about the mounting damage to the rover's six wheels have abated recently, Vasavada said.

Curiosity's handlers think they know how to avoid the types of terrain that inflict the most dings and dents, and they're making some changes to the software that drives the wheels, he explained.

"The combination of all those things makes us confident now that the wheels are going to last as long as we need them to in the mission that we have planned to get higher up on Mount Sharp," Vasavada said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.