A new partnership could pave the way for the first off-Earth assembly line.

Space manufacturing company Made In Space is teaming with NanoRacks, which helps commercial customers make use of the International Space Station, to develop an orbital construction-and-deployment service for tiny satellites known as cubesats.

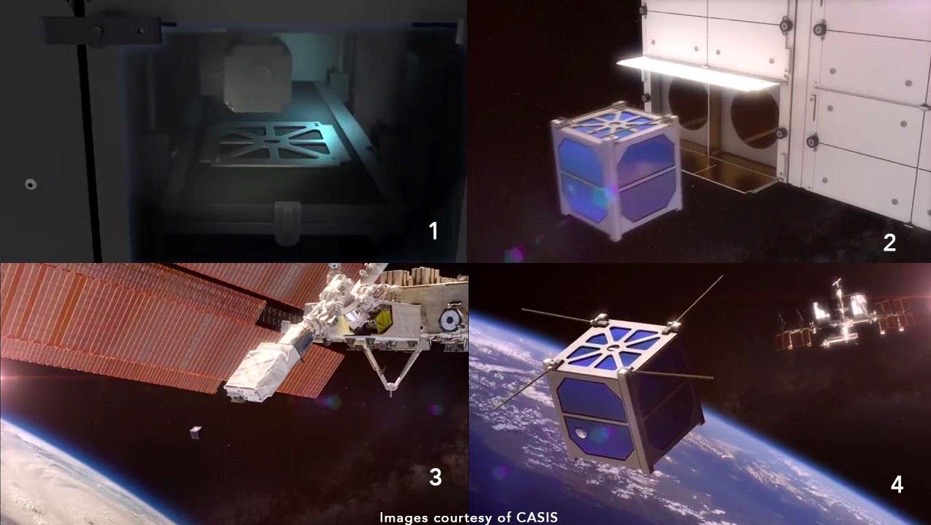

The service, which the two companies are calling Stash & Deploy, will cache a variety of standard and custom cubesat parts aboard the space station. Many of these components will be built by Made In Space's Additive Manufacturing Facility (AMF), a commercial-scale 3D printer that the company aims to launch later this year. [10 Ways 3D Printing Will Transform Space Travel]

Cubesats will be assembled in orbit from these parts and then will be deployed into space. This process should provide a number of advantages over typical Earth-based construction, Made In Space representatives said.

"This is a fundamental shift for satellite production," Made In Space President Andrew Rush said in a statement. "In the near future, we envision that satellites will be manufactured quickly and to the customer's exact needs, without being overbuilt to survive launch or [having] to wait for the next launch."

The first steps of the Stash & Deploy system should be in place by early 2016, Made In Space representatives said.

Made In Space already has some experience with off-Earth manufacturing. The company built the 3D printer that astronauts installed on the space station last fall, as part of a collaboration with NASA called the 3D Printing In Zero-G Experiment (or 3D Print, for short).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA owns that device, which printed out a number of parts during a test run late last year. But Made In Space will retain ownership of the AMF and make it available to a variety of commercial customers.

NASA is a big believer in space-based 3D printing, saying the technology has the potential to help open up the solar system to further exploration. Spacecraft equipped with a 3D printer — which builds objects layer by layer out of plastic, metal or other "feedstock" materials — would be more self-sufficient and wouldn't have to carry as many spare parts, agency officials have said.

Made In Space shares this optimism, and is working to get its technology ready for broader application in the final frontier. For example, last month, the company completed a round of successful vacuum-chamber tests here on Earth. The results suggest that 3D printing can be done outside of spacecraft, in the harsh environment of space, company representatives said.

"These preliminary tests, combined with our experience with microgravity additive manufacturing, show that the direct manufacturing of structures in space is possible using Made In Space-developed technologies," Mike Snyder, Made In Space's chief engineer, said in a different statement.

"Soon, structures will be produced in space that are much larger than what could currently fit into a launch fairing, designed for microgravity rather than launch survivability," Snyder added. "Complete structural optimization is now possible in space."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.