Could the first Mars colony be called Buffettville, or Zuckerburgh?

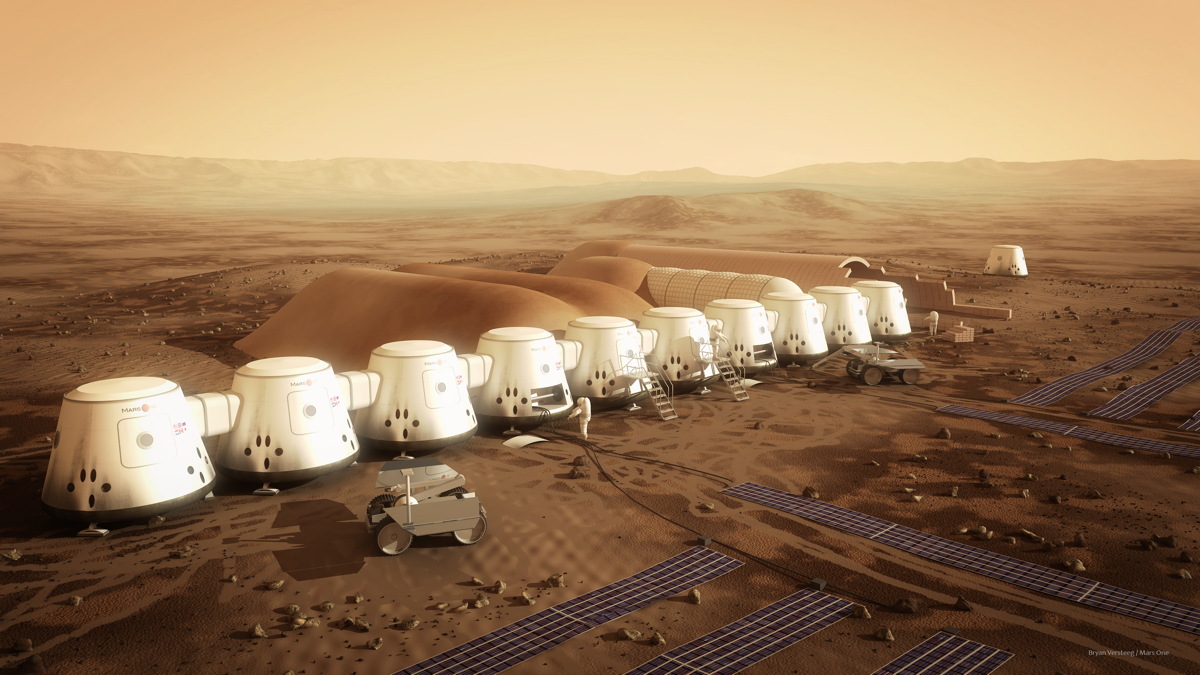

The Netherlands-based nonprofit Mars One aims to establish a permanent settlement on the Red Planet, beginning with the touchdown of the first four pioneers in 2027. The biggest challenges facing the project are financial rather than technical, so a big donation from a deep-pocketed person concerned about his or her legacy could make a huge difference, Mars One representatives said.

Mars One "is so ambitious and — I think 'crazy' is the right word — that we might actually get a phone call from a billionaire who says, 'I want to make this happen. I want the first city on Mars to be called Gatesville or Slim City," said Mars One co-founder and CEO Bas Lansdorp, presumably referring to Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and Mexican tycoon Carlos Slim Helu. [Images of Mars One's Red Planet Colony Project]

"That will change everything," Lansdorp said Aug. 13 at the 18th annual International MarsSociety Convention, which was held in Washington, D.C.

Debating Mars One

Lansdorp made his remarks during an organized debate about the feasibility of the Mars One project, which pitted Lansdorp and Barry Finger, director of life-support systems at Paragon Space Development Systems Corp., a Mars One supplier, against MIT graduate students Sydney Do and Andrew Owens.

Do and Owens helped perform a 2014 study that questioned the feasibility of Mars One's plan. The duo explained the study team's findings, and its reasoning, during the debate.

The organization has estimated that taking these steps, and then landing four astronauts on the Red Planet in 2027, will cost about $6 billion.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Do and Owens said that's overly optimistic. It cost NASA about $102 billion in today's dollars to put Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon in 1969, the two grad students pointed out. And Mars One's plan will require 14 separate launches, they added, as well as the development of seven new systems, including an intelligent rover; technology capable of delivering to the Martian surface payloads at least 7.5 times as heavy as the 1-ton Curiosity rover, which is the heftiest thing ever landed softly on Mars to date; and life-support systems of unprecedented endurance and reliability.

"Can they do all of this — accomplish these development challenges — for $6 billion in the next 12 years?" Do asked the audience. "Our belief, based on the data, the analysis that we've made and the historical analysis that we've done, is that no, they cannot do this, and it is infeasible."

Mars One's long-term vision involves launching new crews of four toward the Red Planet every two years to keep building up the off-world settlement. (There are no plans at the moment to bring any of these pioneers back to Earth.) The organization estimates that each of these subsequent crewed missions will cost about $4 billion. [The Boldest Mars Missions in History]

But the costs associated with such a growing colony would rise unsustainably over time, as a result of the ever-increasing need for spare parts (which in turn would require more landers and more launches), Do and Owens said.

"Spares are a very, very significant problem," Owens said. "This was really the fundamental conclusion of the paper that we wrote a year ago — the Mars One strategy of one-way missions is inherently unsustainable without a Mars-based manufacturing capacity."

The counter-argument

Like Do and Owens, Lansdorp cited NASA's manned moon program. But the Mars One CEO drew different conclusions about Apollo, saying it showed how much can be accomplished in a short amount of time.

When, in May 1961, President John F. Kennedy made his famous speech promising to land an astronaut on the moon by the end of the decade, the space age was just four years old, Lansdorp pointed out. Half of the United States' unmanned attempts to reach orbit had failed by May 1961, and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human being to reach space just the month before, Lansdorp added.

"We needed rockets to go to the moon. We needed portable life-support systems, moon landing systems, computers," Lansdorp said. "All that was developed, and more, in just eight years' time." [NASA's 17 Apollo Moon Missions in Pictures]

He also implied that Do and Owens are getting too hung up on the numbers.

"Mars One's goal is not to send humans to Mars in 2027 with a $6 billion budget and 14 launches," he said. "Our goal is to send humans to Mars, period."

Indeed, Mars One's time line has changed twice: The organization originally proposed putting boots on Mars in 2023, then pushed that back to 2025, and then 2027.

Lansdorp said he agreed with Do and Owens that $6 billion might be too low an estimate, and he stressed that Mars One's plans could well change again in the future. The MIT duo protested that, if Mars One is still mapping out its basic concept, the group doesn't really have a plan, and feasibility is therefore impossible to assess.

"Did Kennedy have a plan?" Lansdorp responded, adding that the basic technologies necessary to set up Mars One's envisioned colony already exist. "We are presenting something that is feasible. There is nothing that cannot be done."

For example, life-support systems based on those already in use on the International Space Station could indeed work for the Mars colony, said Finger. (He and some of his colleagues at Arizona-based Paragon recently conducted a detailed life-support study for Mars One.)

"There's no fundamental, technical reason the life-support system for this mission can't be put in place," Finger said during the debate. (You can watch the Mars Society debate online here: http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/70819066.)

More funding needed

Mars One aims to pay most of its bills by staging a global media event around the colonization project, but the organization needs investment money to pay for work during the early stages. That money has been a bit hard to come by; funding shortfalls were the main reason the manned landing has now slipped to 2027, Lansdorp said.

The group is trying to raise about $15 million at the moment, which it will use to hire more staff, pay for key studies that will show how to implement the Mars One vision in detail and build a simulated Red Planet outpost on Earth, Lansdorp said.

Mars One should have that money by the end of the year, he added, and will likely be able to present a detailed colonization plan by late 2017 or so.

Everything would probably be considerably easier if Mars One could get a billionaire on board.

"Imagine Mars One having $6 billion in the bank," Lansdorp said. "Suddenly, all the big aerospace companies that have some kind of capability of landing systems on Mars will be calling us and making us offers for a reliable transportation system."

Billionaires in space

Mars One isn't just waiting around, hoping for a tycoon to swoop in with a blank check. But such a "positive surprise," as Lansdorp described the scenario, is perhaps not too far-fetched, because a number of billionaires are already heavily involved in space exploration.

Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos started the aerospace company Blue Origin in 2000, for example, and PayPal co-founder Elon Musk set up SpaceX two years later with the explicit aim of helping humanity colonize Mars.

British entrepreneur Richard Branson established suborbital spaceflight company Virgin Galactic in 2004, and Bill Gates' fellow Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen started Stratolaunch Systems — which aims to launch payloads to space beneath a gigantic airplane — with renowned aerospace engineer Burt Rutan in December 2011.

And asteroid-mining company Planetary Resources, which was founded in 2012, counts billionaires Larry Page, Eric Schmidt, Ross Perot Jr. and Charles Simonyi among its investors (along with filmmaker James Cameron, who has a net worth around $700 million).

But the above billionaires are just the tip of the iceberg: There are 1,826 billionaires around the world, according to a recent estimate by Forbes magazine.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.