The more scientists learn about Pluto, the more interesting the dwarf planet gets.

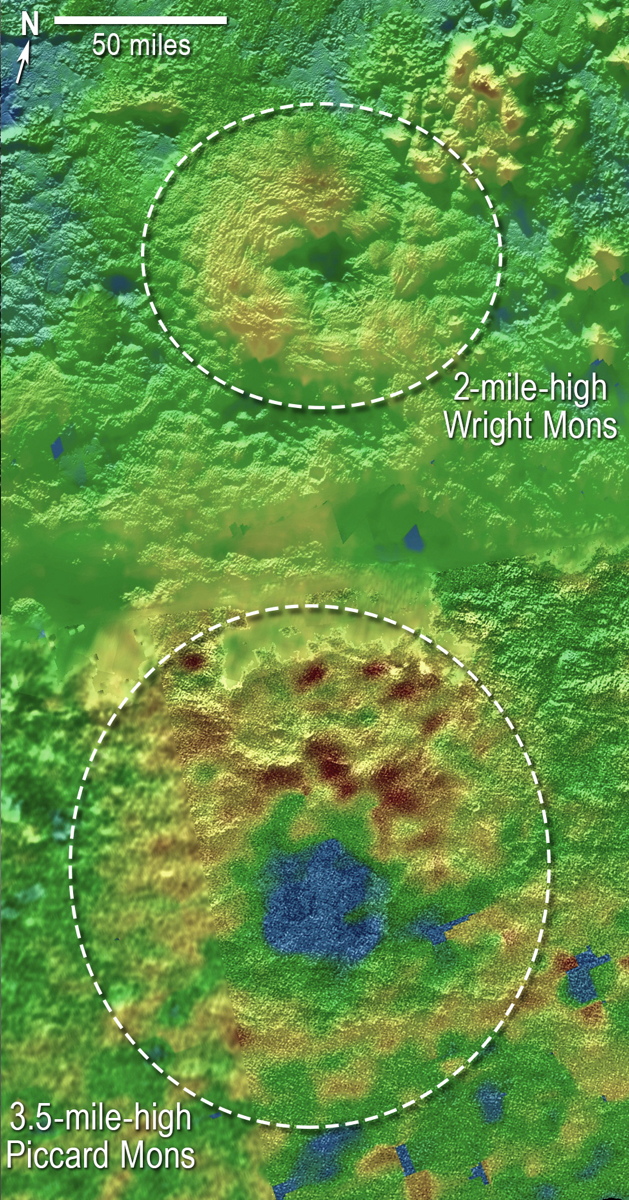

Two of the towering mountains observed by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft during its historic July 14 flyby of Pluto — the 13,000-foot-high (3,960 meters) Wright Mons and the roughly 18,000-foot-high (5,500 m) Piccard Mons — appear to be ice volcanoes, mission team members said in a new video.

"From New Horizons' vantage point, these features look just like volcanoes do on Earth when seen from orbit," mission team member Amy Shira Teitel said in the video, which was released today (Jan. 7). [NASA's New Horizons Pluto Mission in Pictures]

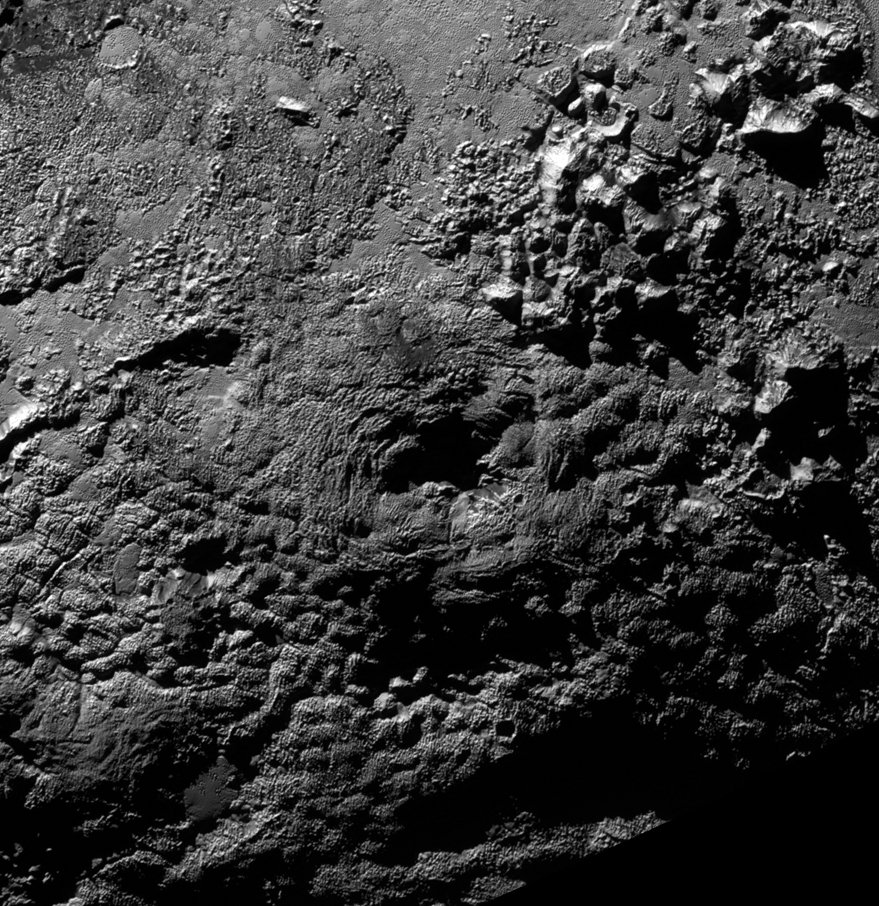

Specifically, the two peaks both feature large holes in their summits, which likely formed when material erupted from underneath, causing the mountaintops to collapse. In addition, the flanks of Wright Mons and Piccard Mons sport an odd "hummocky" texture that could be the residue of past volcanic flows, New Horizons scientists said.

Whereas Earth volcanoes expel superhot molten rock from a subsurface magma chamber, Pluto cryovolcanoes would likely "erupt with a melted slurry containing water ice and frozen nitrogen, ammonia or methane," Teitel added.

New Horizons didn't catch either Wright Mons or Piccard Mons during an eruption, so the cryovolcano interpretation remains just a hypothesis at the moment. But it's one with a lot of explanatory power.

"Cryovolcanism could provide an important clue in understanding Pluto's geologic and atmospheric evolution," Teitel said in the video.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

New Horizons zoomed within just 7,800 miles (12,550 km) of Pluto's surface during the July 14 flyby, returning the first-ever good looks at the dwarf planet and its five moons. The probe's observations showed that Pluto is a varied and diverse world with big ice mountains and flowing nitrogen-ice glaciers, among other intriguing features.

New Horizons also found that a huge swath of Pluto's famous heart-shaped region — which has informally been named Tombaugh Regio, after Clyde Tombaugh, the American astronomer who discovered the dwarf planet in 1930 — hosts no detectable craters, suggesting that the landscape is very young. How Pluto has managed to stay geologically active more than 4.5 billion years after its formation is a mystery that mission scientists are still trying to solve.

To date, New Horizons has beamed home just 25 percent or so of the data it gathered during the flyby; all of the images and measurements should be on the ground by this October or November, team members have said.

The probe is currently cruising toward a small object about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond Pluto called 2014 MU69, and will perform a flyby of the body on Jan. 1, 2019, if NASA approves and funds a proposed extended mission.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.