Mobile Stargazing: A Universe of Astronomy Apps to Explore the Sky

There are myriad astronomy apps for exploring the sky on mobile devices.

With a few swipes of your finger, these apps can help you identify objects, take you on a tour of the night sky and even plan your stargazing for that upcoming holiday. Whatever your level of interest in astronomy — from casual stargazer to professional astronomer — there is likely an app to suit you.

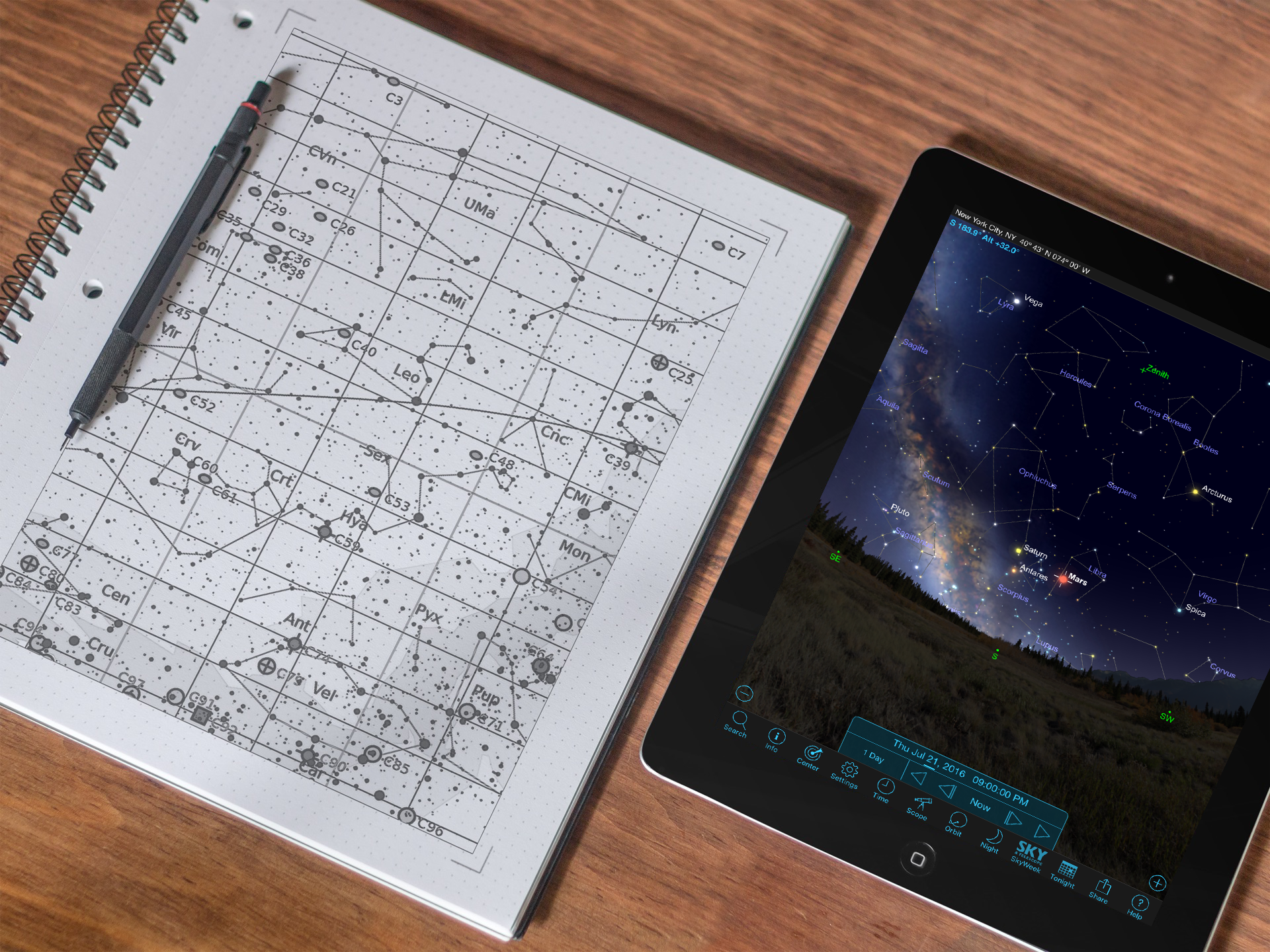

In this edition of Mobile Stargazing, we'll focus on sky-charting apps — mobile star atlases loaded with features that run circles around stuffy old paper atlases. There are many to choose from, at a range of prices. The Apple App Store (iOS) and the Google Play store (Android) will list the more popular ones. You can watch for price drops on your favorite apps (or even when they become free) on websites such as AppShopper if you are using iOS, or AppSales if you are on Android. [Gallery: Amazing Skywatcher Photos from Around the World]

Let's look at how sky-charting apps work, how to set them up and what to consider when you're browsing the App Store or the Google Play store.

How sky-charting apps work

The stars, and the deep-space objects outside our solar system, are so distant that they effectively appear fixed in place with respect to one another, and this has allowed maps of the sky to be created. Over time, the star patterns that ancient skywatchers first imagined have become standardized into 88 modern constellations that completely cover the sky. Each one has a fixed boundary, with no gaps or overlap, so everything in the sky can be indexed to a particular constellation.

The regular motions of the Earth's rotation every 24 hours and the planet's orbit around the sun every 365.25 days leave the stars in predictable positions. The same stars are overhead at the same time on the same date every year. And where you are located on the Earth determines which constellations are in your sky, too. After all, the midnight sky for a stargazer in the Southern Hemisphere will be much different from that of a skywatcher in the Northern Hemisphere, even within the same time zone. (That's why astronomers take vacations!)

Solar system objects — such as Earth's moon, the planets, comets and asteroids — move constantly, in a predictable way, so these are handled by algorithms in the app that know the objects' orbital parameters, and therefore can accurately predict where they will be at any given time — past, present or future. The orbits of newly discovered asteroids and comets have to be loaded by the app via software updates or by downloading the data from the Web from time to time. [Our Solar System: A Photo Tour of the Planets]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mobile sky-charting apps work because our devices accurately know the date and time, as well as our location (via GPS or Wi-Fi), and therefore what's up in the sky. By using the built-in compass and gyroscope, your mobile device knows where it's pointing and can show you a virtual map of any part of your sky. Add some onboard memory or access to the Internet, and you've got an encyclopedia of astronomy data only a tap away. Unlike a paper chart, you don't even need a flashlight — and you don't have to worry about dew making your paper chart soggy!

What they display and what's under the hood

For the most part, everything you'll observe in the sky falls into a category or class of objects. Beyond the moon and bright planets are the individual stars. Next out are the deep-sky objects — star clusters, nebulae and galaxies, things that appear as "faint fuzzies" without (and sometimes even with) a telescope.

Every object has a designation (name or number), a coordinate, a visual brightness value (called magnitude) and other characteristics depending on the object's type. Stars have spectral classifications that relate to their color, temperature and distances. Galaxies have apparent sizes (some are wider than the moon!) and structure classifications (spiral, elliptical, etc.). The more advanced apps store all of this data and more, giving you a richer experience but requiring more memory storage or an Internet connection to retrieve the data.

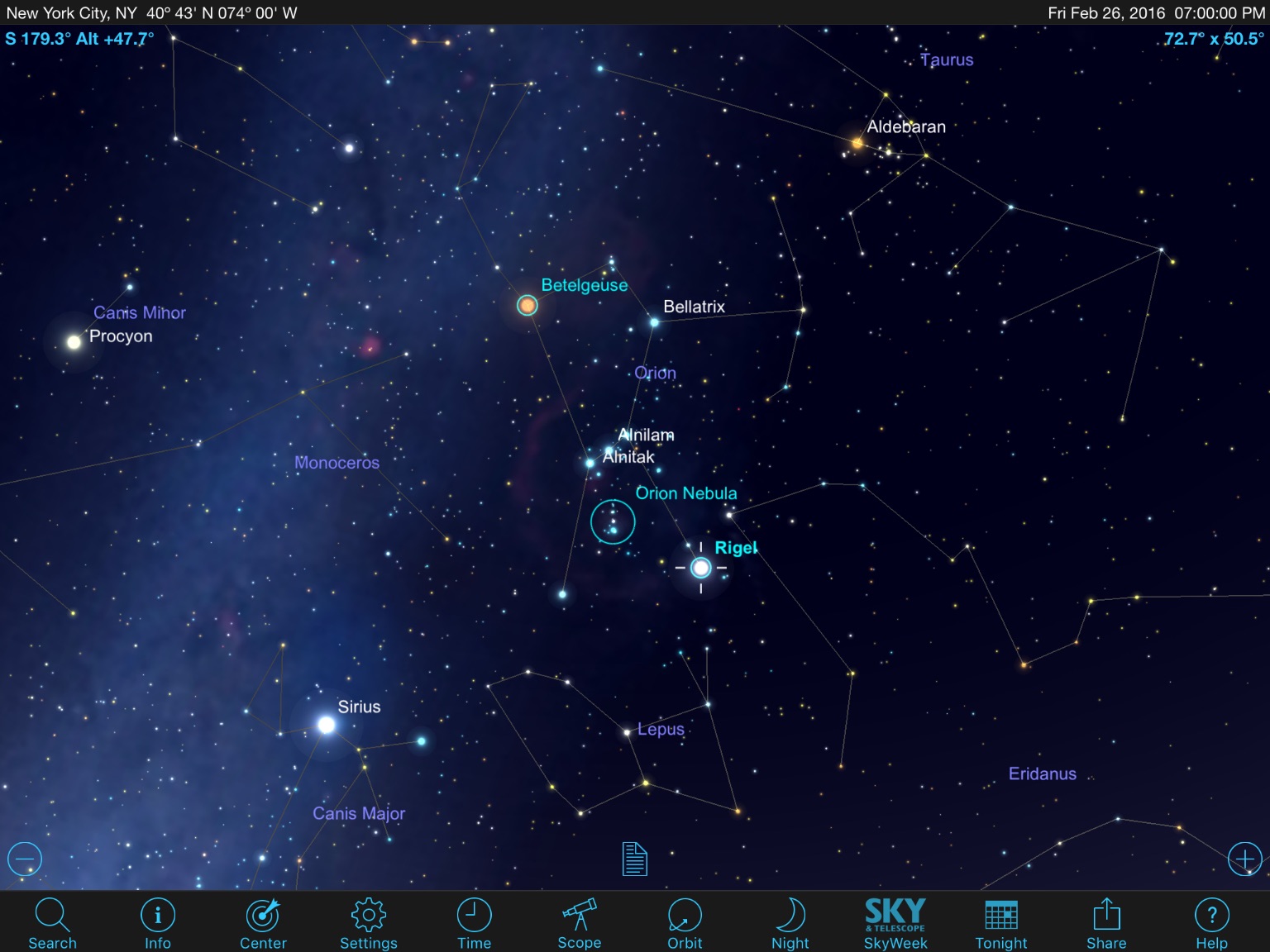

The way objects are displayed in an app usually reflects the objects' visual characteristics. For example, a star's brightness and color will be suggested by the size of the symbol and its tint. Deep-sky objects might be shown in the sky using actual photographs, artistic renderings or symbols assigned to the object type. Aside from a few dozen bright ones, these objects can't be seen with the naked eye, and the app is simply reporting its position for you to track down in a telescope or binoculars. Most astronomy apps attempt to present the objects in a realistic fashion. But for some famous objects, the colorful and vibrant photographs you see in the app won't resemble the actual view with your unaided eyes or telescope.

Most sky-charting apps have a way to manage the objects by category and/or observing lists. The Messier List — 110 of the more interesting and brighter deep-sky objects visible from the Northern Hemisphere — is almost universally included. It was compiled and published by comet hunter Charles Messier in 1781, and was later expanded. You'll see the objects labeled with an "M." As an example, M42 is also known as the Great Orion Nebula.

If you're a Southern Hemisphere observer, you won't be able to see the more northerly of the Messier objects, so watch out for apps that only include that list. Other common lists include the Caldwell List, another 110 showpieces of the sky covering the entire celestial sphere; and the New General Catalogue (NGC for short), which contains thousands of objects. Ideally, the app will let you sort for the brighter and easier-to-see objects.

Most apps show the Milky Way as an outline or a photographic image. While beautiful, it's helpful if the Milky Way rendering can be switched off or dimmed so you can see the constellation or foreground objects in that part of the sky. Many apps allow the Milky Way to be shown as it would appear in other wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is fun to try out; check your Settings menu. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy (Gallery)]

If you want to really learn about astronomy, take a look at the higher-quality apps, which offer way more — a wealth of information about objects' discovery and folklore, sample astrophotographs and scientific data, such as their evolutionary history. Remember, if your app retrieves information off the Web on demand, this requires a live data or Wi-Fi connection, which is not always available if you're stargazing in a remote, dark-sky location.

You'll want to select an app that displays the sky in a way that's easy and pleasing to you. In a future column, we'll delve deeper into advanced features, such as heads-up and augmented-reality displays.

Setting up and getting started

Before you can use an app to show you the sky, it needs to know where on the Earth you are, usually by using your device's GPS or Internet information. There should also be an option that allows you to select from a list of cities (within 60 miles, or 100 kilometers, is good enough), or to type in your latitude and longitude. This also allows you to explore the sky over other parts of the world. Just don't forget to set it to your home location when you're done exploring!

Next, you need to establish the time and date. Most apps will start up using the current time. You may also wish to see what the sky will look like later that night, or on another particular date and time. — for example, if you want to check out an unusual object your friend saw in the southeastern sky the other morning at 6:30 a.m. The best apps allow you to dial in the year, month, day, hour, minute and second, and to revert to real time by selecting "now." They'll also allow you to alter the flow of time, using Play, Pause, Fast-forward and Reverse buttons, or by selecting the time increment and swiping to advance or reverse.

Want to simulate the solar eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017? Dial it up, and watch it unfold in fast-forward! A number of apps have quick links to sunrise, sunset and other times.

At this point, your app is ready to show you your sky. Assuming your location, time and date are correct (are they?), if you're having trouble matching the app with the sky, here are a few tips. First, get used to how the horizon appears on the app. Some simple apps, like Google Sky Map, only offer a line indicating the horizon, with no way to hide the part of the sky that's below it, and this can be confusing at first. If you can't find the horizon line, see if it's been switched off. I prefer apps that allow both opaque and transparent ground.

Second, the accuracy of your device's compass and gyroscope play a large part in how well the app works. For example, the compass can be affected by a nearby vehicle or power line, and the gyroscopes in Android and iOS devices can become inaccurate. If this happens, your phone won't think it's aimed where you are pointing it.

Most devices offer a way to calibrate the sensors. An excellent test is to aim for the moon and compare where it appears on your device. If it's not in the same place, then check the app's location and time setting. If those are correct, walk a few steps away, and try again. If it's still off, you may need to calibrate your device. It's also possible that some apps just may not work as well with your hardware; another app might work better. Read the comments before you purchase the app.

Finally, the app may display far more stars than you're seeing, making it difficult to match things up. If you've done any stargazing under city skies, you'll know that the number of visible stars dramatically decreases when light pollution is a factor.

To indicate the brightness of stars and other objects, astronomers use a term called visual magnitude. The better apps have a magnitude adjustment that permits you to limit how many of the stars it displays. If you're a beginner, I recommend configuring it to match your sky conditions. Just slide the control until you see about the same number of prominent stars. The Big Dipper or a bright constellation like Orion is great to use. Once you are more familiar with the sky, you'll want to bring the fainter stars back, especially if you're hunting through a constellation with your binoculars.

What's next?

So you have an app that suits your needs, and you've configured it for your location and the current time. What's next? Here are some easy objects that you can try finding in late February 2016. Orion and his famous three-starred belt are well placed due south in the evening. Your app should show you the bright reddish star Betelgeuse at his eastern shoulder, the bright-blue star Rigel at his western foot and the beautiful Orion Nebula, also known as Messier 42, in the sword hanging below his belt. Use your binoculars for that one!

Nearly overhead is the bright-yellow star Capella in the constellation Auriga the Charioteer, and low in the east will be very bright Jupiter, king of the planets, which is sitting just below Leo the Lion.

In our next column, we'll look at apps that focus on Jupiter — the Great Red Spot, the gas giant's four Galilean moons, what's inside the planet and some apps created for planetary exploration missions.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.