Astronomers are trying to take the measure of Planet Nine before the hypothesized world has even been discovered.

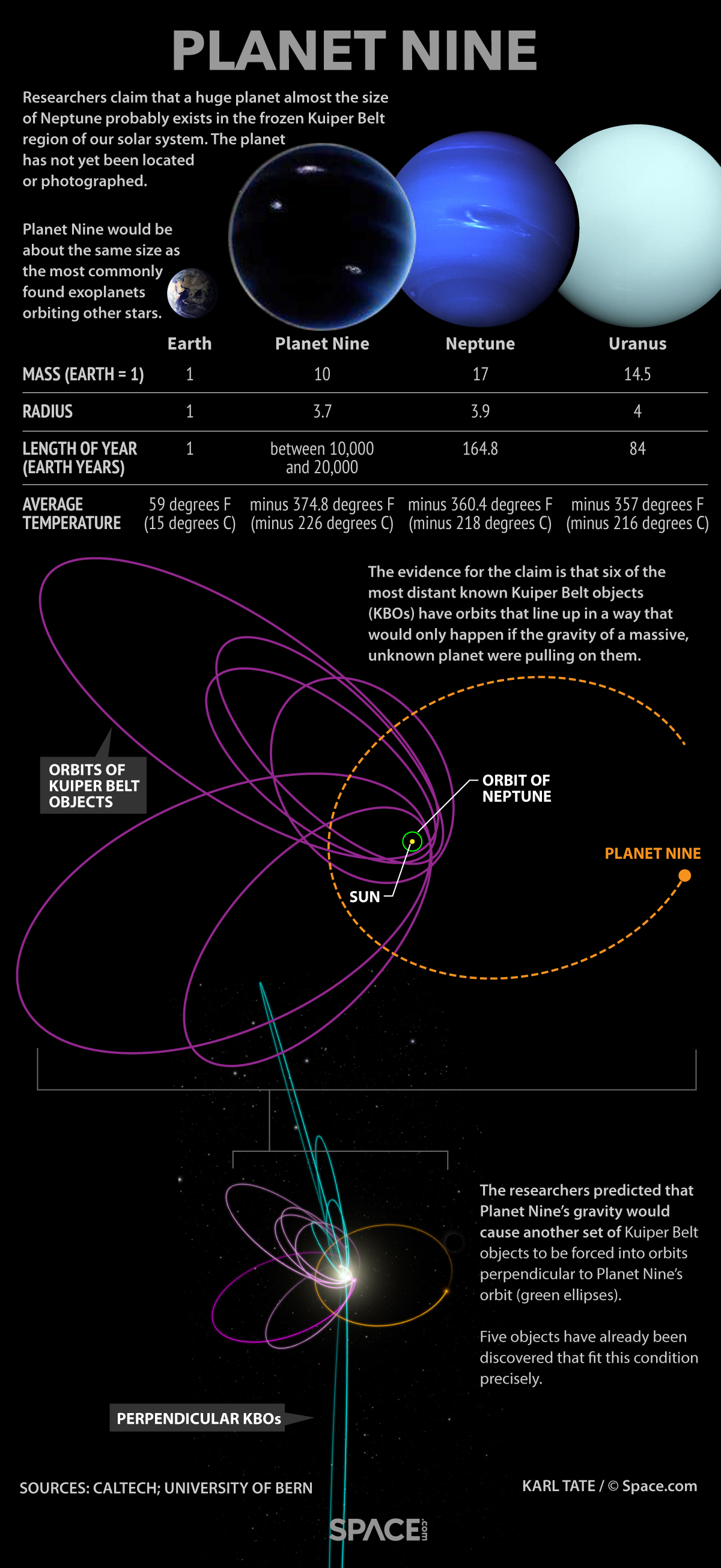

Earlier this year, astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown, both of whom are based at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, proposed that a large planet lurks undetected in the outer solar system, far beyond Pluto's orbit.

Batygin and Brown didn't spot this prospective Planet Nine; rather, they inferred its existence based on the orbits of a half-dozen objects in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune. [Planet Nine: The Evidence for a New Giant Planet in Pictures]

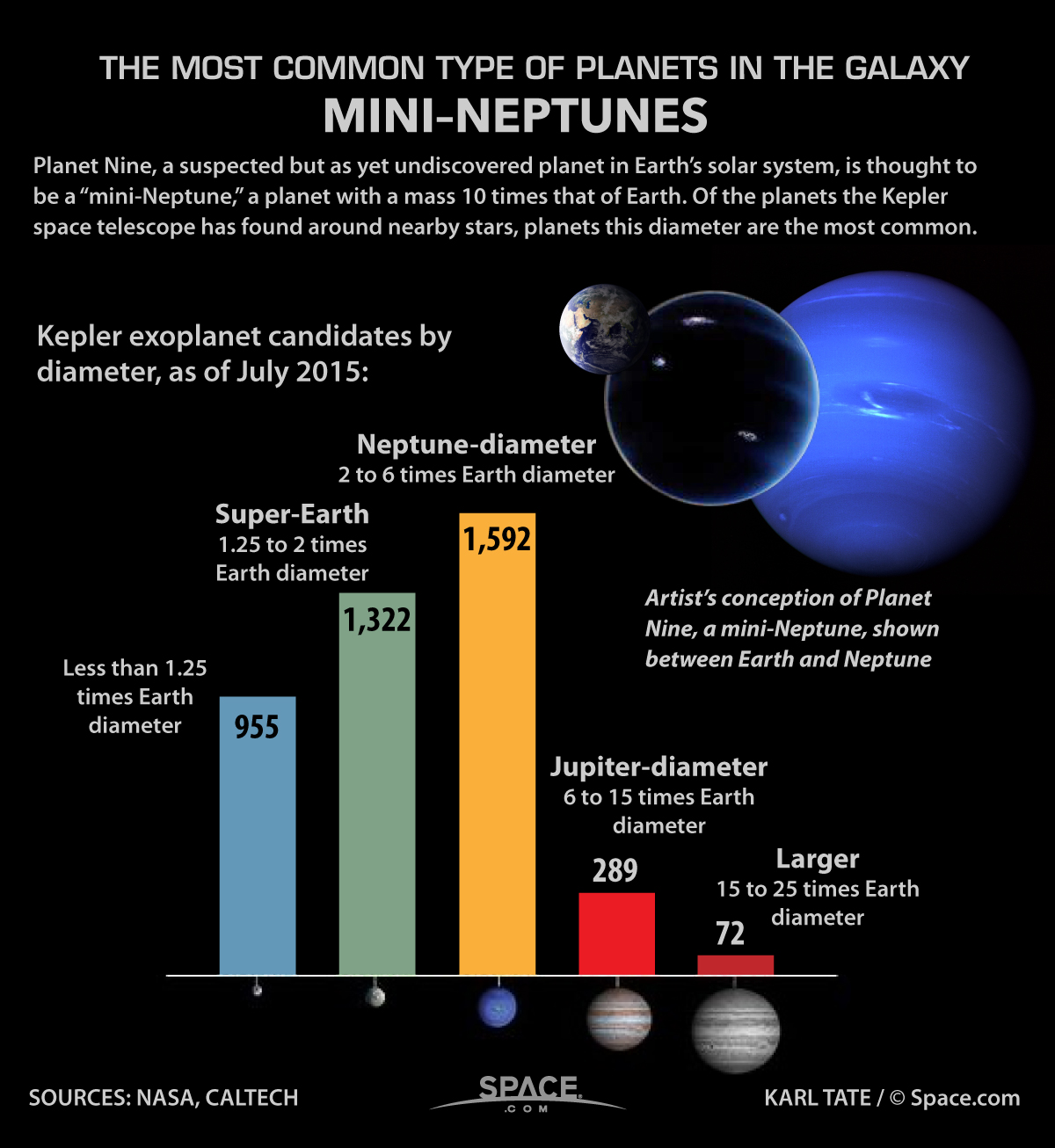

These objects' orbits suggest that Planet Nine may be about 10 times more massive than Earth, and may circle the sun at an average distance of 600 astronomical units (AU) or so, Batygin and Brown said. (One AU is the average distance from Earth to the sun — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

Now, a new study models what Planet Nine — which, contrary to the claims of a recent New York Post video, will not destroy the Earth — might look like if those parameters are on the money.

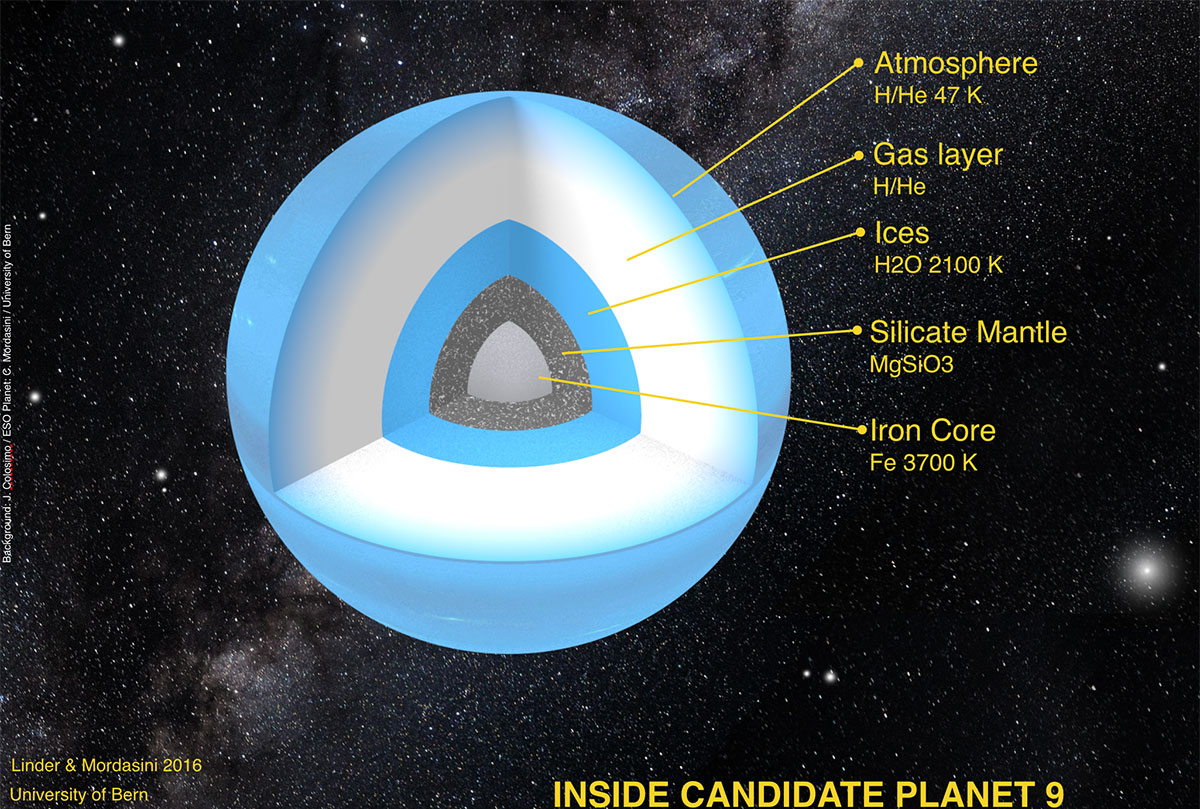

Astrophysics professor Christoph Mordasini and his Ph.D. student Esther Linder, both of the University of Bern in Switzerland, assumed that Planet Nine — if it exists — is basically a smaller version of the "ice giants" Uranus and Neptune, with an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen and helium.

The duo then calculated that such a 10-Earth-mass Planet Nine would be about 3.7 times wider than our planet, with a temperature of minus 375 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 226 degrees Celsius; 47 degrees Kelvin).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This means that the planet’s emission is dominated by the cooling of its core; otherwise, the temperature would only be 10 Kelvin," Linder said in a statement.

Since reflected sunlight would contribute very little to the total radiation emitted by Planet Nine, it would be much brighter in infrared light than in visual wavelengths, Mordasini and Linder said.

"With our study, candidate Planet Nine is now more than a simple point mass; it takes shape, having physical properties," Mordasini said in the same statement.

The researchers also used the results of their modeling work to investigate just how detectable Planet Nine might be. They determined that the various sky surveys that astronomers have already performed were likely incapable of spotting a Planet Nine that's less than 20 Earth masses, especially if the mysterious world were close to aphelion (the planet's farthest point from the sun during its highly elliptical orbit). But NASA's Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer satellite likely would have spotted a Planet Nine harboring more than 50 Earth masses.

"This puts an interesting upper mass limit for the planet," Linder said.

Further surveys and future instruments — such as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which is currently being built in Chile — should be able to confirm or rule out the existence of Planet Nine, the researchers said.

The new study has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.